• 342a. Caroline to Wilhelm Gottlieb Becker in Dresden: Jena, 21 January 1802 [*]

Jena, 21 January 1802

My concern for the wishes of an extremely valued friend, esteemed Herr Professor, prompts me to appeal to your friendship and your remembrance in soliciting assistance for both her and me in the form of advice and, if possible, also deed; trusting that I will receive a favorable hearing, I would like to present the matter to you without further ado.

One among the several daughters of Madam Gotter in Gotha has from early childhood demonstrated both talent and inclination for the drawing arts and has also been consistently engaged in such under Döll’s guidance. A period of extreme ill health, however, set back her intentions of devoting herself rigorously and exclusively to her art, something to which, I might add, her entire personality seems to destine her. [1]

It was not until last summer that steps could finally be taken enabling her to receive training in drawing in Weimar under Kraus, at least nominally, since it was actually Professor Meyer who was so kind as to assist her and who assures us with his Swiss accent that she does indeed possess “respectable talent.” It was here that she first began practicing with a brush, producing various quite nice portraits. [2] Although this winter she is again drawing under Döll’s guidance, both she and her mother very much wish for her to be able to take some significant steps forward this coming summer. She has not yet seen anything beyond what is in Weimar and Gotha. It would be splendid if she could spend the summer in Dresden. [3]

Now, could you possibly tell me whether there is not some master or other there to whom one might entrust her with a good conscience? — Her specific goal would be portraiture. [3a] — I very much doubt whether Graf even occupies himself with such now, and Grassy is perhaps too distinguished for my shy young client. It goes without saying that I am not considering Gareis; [4] nor do I have the best opinion of Hartmann considering what he entered in the Weimar exhibition. [5] In a word, I know of no one, and would very much like to hear your opinion on the matter.

The second point is to find a house where she can live without inconvenience and disruption. I hope I am not being indiscreet in confessing to you that I cannot really consider the Naumanns, [6] nor several others either, e.g., the Tieks, who themselves may well be residing outside the city during the summer, where I would moreover fear that Cäcilie (thus her name) would not have sufficient peace and quiet and would inevitably be distracted by her own interest in so many other things. [7] I must also further confess to you my wish that you and your spouse might make a small room available to her in your own house and also otherwise take care of various of her needs

In you she would gain a cordial supervisor and a well-versed advisor in the arts, and indeed would also be surrounded by the objects of art in your house during those hours when the other treasures are not accessible to her. [8] And your wife would doubtless be quite kind to her. Moreover your house and garden would certainly provide cheerful encouragement for her. I for my part can recommend her to you as an extremely good girl, about 18 years old, not really pretty, but quite bright and intelligent, especially when she plucks up her courage.

I do hope you will be so kind as to relate your own opinion of the matter to me and at least to make some suggestions even if you yourself be unable to fulfill our wishes. Should you not be so disinclined, however, I am sure we could easily come to an agreement concerning boarding costs.

Schlegel is in Berlin, where since the beginning of December he is delivering lectures before a mixed and not inconsiderable company. Although my own, completely decimated health prevented me from accompanying him, I will probably be in a position to follow after him next month to Berlin if the weather be favorable, where we will then be staying until Easter. [9]

Beforehand, however, I would very much like to have settled this matter for my friend. [10] Cäcilie’s younger sister has been staying with me here since last summer. [11]

Stay well and please do forgive these hastily written lines. Please also be so kind as not to relate this matter to anyone until further notice.

Caroline Schlegel

Notes

[*] Source: Krisenjahre 2:518–20; not in Erich Schmidt, (1913).

Caroline had already written Wilhelm Gottlieb Becker on 23 September 1799 (letter 244a) trying to place Sophie Bernhardi’s manuscript of Wunderbilder und Träume, which was ultimately published in Königsberg in 1802. Back.

[1] Caroline mentions Cäcilie Gotter’s artistic talent as early as 1797 in a letter to Luise Gotter on 7 September 1797 (letter 185); see also her letter to Luise on 11 February 1798 (letter 195), in which she also, however, mentions Cäcilie’s sickliness.

Luise herself had mentioned the illness to Caroline earlier; see Caroline’s letter to her on 15 October 1797 (letter 188). Caroline similarly mentions the illness toward the end of her letter to Luise on 5 October 1799 (letter 246).

By 6 March 1801 (letter 296), Caroline writes to Wilhelm Schlegel that Cäcilie’s health was already “very good.” Back.

[2] E.g., during an earlier (1798) stay in Jena, a portrait of Schiller; see Caroline’s letters to Luise Gotter on 11 February (letter 195) and 21 February 1798 (letter 196). Back.

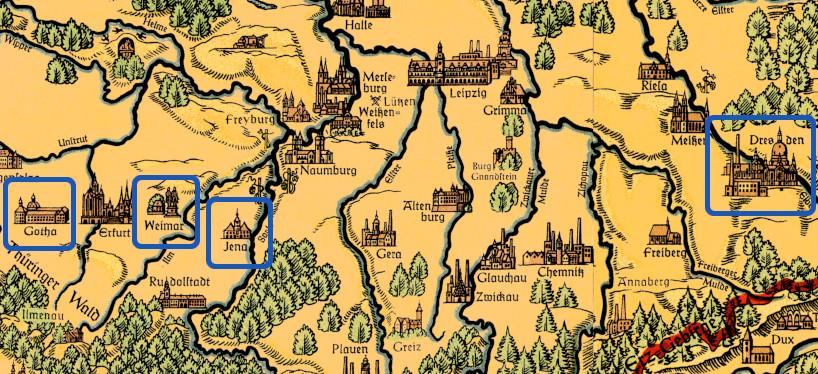

[3] Jena is located 65 km east of Gotha and 150 km west of Dresden; Gotha is similarly 45 km west of Weimar, the latter 20 km west of Jena (Rudolf Koch and Fritz Kredel, Deutschland und angrenzende Gebiete [Leipzig 1937]):

[3a] Representative scenes portraying women sitting for portraits at the time (first illustration: from the story by W. G. Becker, “Der Maler,” Taschenbuch zum geselligen Vergnügen 14 [1804], 1–61; illustration from the next issue, Taschenbuch zum geselligen Vergnügen 15 [1805]; second illustration: Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, “Porträtsitzung der Frau Chodowiecka” [“Portrait sitting for Frau Chodowiecka”], Von Berlin nach Danzig: Eine Künstlerfahrt im Jahre 1773, von Daniel Chodowiecki. 108 Lichtdrucke nach den Originalen in der Staatl. Akademie der Künste in Berlin, mit erläuterndem Text und einer Einführung von Wolfgang von Oettingen [Leipzig 1923], no. 44):

[4] Why Caroline should have such an opinion of Johann Franz Gareis is unclear; see in any case her remarks to Wilhelm in her letter to him on 11–14 January 1802 (letter 340). Back.

[5] Biographical accounts generally do not place Ferdinand Hartmann in Dresden until 1803, which conflicts with Caroline’s assumption here that he was already residing there. — See supplementary appendix 330.1 concerning the competition of 1801.

During the autumn of 1801, Wilhelm seems to have mocked the entries in the competition in a letter to Hans Christian Genelli, who responds on 15 October 1801 (Körner, [1930], 1:133) that,

indeed, at the moment we might have wished for no greater feast than what you served us with this colorful assortment of Achilles, each of which in its own way manages to be foreign without a single one succeeding in attaining the style of antiquity. All of them greatly entertained us with their enormously comical expressions.

In any event, Hartmann himself had had a falling out with the artistic views of the circle around Goethe during the 1801 competition. After winning the 1799 competition, his notions and those of the Weimar Friends of the Arts differed not inconsiderably concerning the execution of the new theme. See Karl Goedeke, Goethe und Schiller, 2nd rev. ed. (Hanover 1859), 217–18:

The goal of the art competition was to arouse interest among painters and drawers for the ideas propagated by Goethe’s periodical Die Propyläen. Heinrich Meyer and Goethe together stipulated the theme, and a modest prize was awarded for the best pieces.

he competitions began on 3 September, the duke’s birthday. The theme for the first competition (1799) was Aphrodite’s introduction of Helen to Paris. Among the nine entries, those of Ferdinand Hartmann from Stuttgart and Heinrich Kolbe from Düsseldorf were awarded first prize.

The competitions lasted until 1805, when the war interrupted them. Although the influence of what was known as the “classical manner” inculcated during these competitions was not insignificant, it did not endure. The painters themselves followed these guidelines, but not really out of any genuine conviction, and even less from any natural inclination.

When the previous winner Hartmann arrived in Weimar in 1801 and was charged with doing another composition, namely, how Admet, despite the presence of the corpse in the house, receives and shows his hospitality to Hercules, the Weimar Friends of the Arts are unable to concur with Hartmann’s views, “because he portrays as something quite realistic what in fact should be symbolic.”

But he was quite correct in not accepting artistic symbolism as the guideline for taste, for the mistake the Weimar Friends of the Arts made was precisely that of trying to force the sensuous independence of painting into the cold symbolism of the plastic arts. Back.

[6] Wilhelm had earlier published the poem “Die verfehlte Stunde” in Becker’s Taschenbuch zum geselligen Vergnügen (1796), 235, set to by music by Naumann, who was, it may be pointed out, already deceased when Caroline is writing here, having died on 23 October 1801. Back.

[7] The Tiecks had lived in Dresden since March 1801, and in her letter to Wilhelm on 16 March 1801 (letter 301), Caroline had already mentioned the possibility of Cäcilie Gotter staying with them in Dresden.

Julie Gotter had in any case perceptively already pointed out to Cäcilie in a letter back on 14 December 1801 (letter 335d.1) that the conditions among the Tieck’s might “perhaps even too pleasant, since having so many people around you all the time and the rather chaotic life they lead might too easily distract you from your work.”

In her letter to Julie Gotter on 15 June 1802 (letter 363), however, Caroline mentions that she had in the meantime learned for sure that the Tiecks were planning to depart Dresden for Giebichenstein, the estate of Johann Friedrich Reichardt, whose second wife was Amalie Tieck’s sister.

In her letter to Wilhelm on 18 June 1802 (letter 364), she mentions that Julie Gotter had asked her to query Amalie Tieck about the possibility again, whereupon Caroline responds to Cäcilie herself in late June (letter 366) that it would not be possible, since the Tiecks would indeed be leaving Dresden during the second half of the summer. Back.

[8] In the Dresden Gallery and Dresden Antiquities Collection. These institutions provided excellent opportunities for a young pupil such as Cäcilie to practice her craft by copying the masters (Göttingisches Taschenbuch zum Nutzen und Vergnügen für das Jahr 1802; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung):

[9] Caroline is being understandably disingenuous about the reasons for her not having accompanied Wilhelm to Berlin.

Caroline did not leave for Berlin until after 18 March 1802. In 1802 Easter fell on 18 April, but Caroline remained in Berlin until 19 May (Rudolf Koch and Fritz Kredel, Deutschland und angrenzende Gebiete [Leipzig 1937]):

[10] Such did not happen. Cäcilie Gotter was never able to study in Dresden, and in 1805 abandoned her hopes to become a portraitist (see Caroline’s letter to Luise Gotter on 6 June 1808 [letter 433]). Back.

[11] Julie Gotter, a guest in Caroline’s Jena apartment at Leutragasse 5 since 31 May 1801, would return to Gotha on 6 March 1802. Back.

Translation © 2016 Doug Stott