Urban Wiesing

The Death of Auguste Böhmer:

Chronicle of a Medical Scandal;

Its Background and Historical Significance [*]

|275| In medical cases involving patients who die despite the attempts of physicians or others to treat their illnesses, retrospective assessments of such attempts at treatment can fall into one of two extremes. Either the treatment was correct but unable to prevent death, or the treatment was incorrect and in fact caused death. After the death of fifteen-year-old Auguste Böhmer from dysentery in Bocklet on 12 July 1800, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling encountered both extremes amid a striking discrepancy of views.

On the one hand, it was attested that he acted quite correctly in a situation in which death was inevitable and unavoidable in any case; on the other hand, his allegedly wholly inappropriate intervention was viewed as having in fact brought about that death. The dispute surrounding this incident was drawn out over several years in the most varied publications and is even today still included in biographies of Schelling. Although an examination of the original documentation gives the impression that these accusations were concerned not merely with assessing the premature death of a young girl, but rather also, or even primarily, with attacking Schelling’s philosophy and the Brownian method from which he drew the principles of his treatment, historiography has not yet adequately assessed this particular aspect. [1]

|276|

The Constellation Prior to the Summer of 1800

Schelling had been a professor of philosophy in Jena since 1798, where his exchanges with Johann Gottlieb Fichte would have a lasting impact on the contemporary philosophical debate. Indeed, Schelling had already made a name for himself and provoked discussion with works conceptually anticipating the ideas associated with his philosophy of nature, [2] ideas that “exerted an extremely stimulating influence on his contemporaries in the medical sciences.” [3] He himself had already enthusiastically embraced the equally revolutionary and disputed medical system of the Scotsman John Brown and as early as 1799 already published a review in the Magazin zur Vervollkommnung der theoretischen und praktischen Heilkunde edited by Andreas Röschlaub, defending that system against inadequate reviews in the respected Jena Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung. In his own periodical, Zeitschrift für spekulative Physik, he compared the significance of Brownianism to that of the philosophy of Immanuel Kant: “Not much later than when Kant’s system began to cause a universal stir in Germany, another system, one no less great and significant in its own way, emerged from undeserved obscurity; I am referring to the Brownian method of healing science.” [4]

During his time in Jena, Schelling became acquainted with Friedrich Schlegel, Wilhelm Schlegel, and the latter’s wife, Caroline. Caroline’s daughter, Auguste, from her first marriage with Franz Wilhelm Böhmer, was also living with them, the only one of Caroline’s four children who had lived beyond childhood, whence also the particularly intimate, qualitatively special relationship between her and her mother. Quite apart from that relationship, however, Auguste’s youth, precocity, and intelligence attracted the attention and interest of many other people as well. One need but cite Wilhelm Schlegel’s reference to “the purest graciousness and most charming amiability,” [5] or Friedrich Schlegel’s remark to Friedrich von Hardenberg: “Well, you have finally taken notice of Auguste. Can you comprehend that one can love such a child the way one loves but once, and can do so despite the fact that one is otherwise variously happy, and compared to which everything else is nothing?” [6]

During the summer of 1799, after Fichte had had to leave Jena as a result of the atheism dispute, and not least through common opposition to his dismissal, Schelling became increasingly integrated into what is more narrowly known as the “Jena |277| circle” around the Schlegel brothers, Caroline, Dorothea Veit, Friedrich von Hardenberg, Ludwig Tieck, and Fichte himself, who returned to Jena in December 1799 for a visit and ultimately to move his family to Berlin in March 1800. The group, despite the disparate views of its various members, was nonetheless united through an intensive exchange of ideas, post-Kantian philosophy, a shared understanding of art, and an overall sensibility of “romantic conviviality.” [7] “The circle’s members, filled with fighting spirit, were itching to engage in intellectual confrontation, profoundly convinced of their calling to proclaim new ideas and directions in the nation’s intellectual life and of the necessity of pioneering the way for those very developments.” [8] It was on the basis of precisely this self-understanding, together with their plans for launching their own literary periodical, that the quarrel between the Schlegels, Schelling, and the Jena Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung commenced; it was particularly in the persons of the latter’s editors, Gottlieb Hufeland and Christian Gottfried Schütz, that the Jena circle sensed in the A.L.Z. “one of the key loci at which resistance to these new ideas and directions was particularly virulent.” [9]

The actual “florescence” of the Jena circle, however, was in fact quite brief, coming about essentially between the autumn of 1799 and the spring of 1800. Personal dissension emerged because of, among other things, Schelling’s incipient love for his later wife, Caroline, who at the time was still married to Wilhelm Schlegel.

Andreas Röschlaub was working as the second physician at the Bamberg General Hospital, whose senior director at the time was Adalbert Friedrich Marcus. This hospital provided both physicians with excellent conditions for practicing medicine according to the medical doctrines of the Brownian method, in which context Röschlaub developed this system further into a theory of excitation in a fruitful exchange with Schelling and the latter’s philosophy of nature. [10] In 1802 Röschlaub received an appointment at the newly established university in Landshut.

The Course of Events in Bocklet in July 1800

In early May 1800, Schelling, Caroline, and Auguste journeyed to Bamberg, where Schelling was planning to engage in medical studies on Brownianism with Röschlaub and Marcus at the Bamberg General Hospital and also deliver lectures on his own philosophy of nature. Caroline in her own turn was planning to consult Röschlaub for health reasons and visit the Franconian mineral-springs spas for the sake of her own recovery from a lengthy bout of nervous fever during the spring of 1800. Quite apart from these official reasons, however, Schelling and Caroline wanted to flee the Jena circle that they might spend some undisturbed time together, something that did not at all escape the disapproving attention of the other members of the circle, especially Dorothea Veit and Friedrich Schlegel. It was especially the secretive and yet quite transparent meeting between Schelling and Caroline during the journey — Schelling having left Jena two days ahead that he might meet up with Caroline and Auguste in Saalfeld — that prompted Dorothea |278| finally to proclaim openly her simmering hostility toward them both. “It never occurs to him that the whole world . . . finds him ridiculous.” [11] Such incipient envy, jealousy, ill-will, and mutual alienation were thus already present even before the journey itself commenced, and the coming events merely made the eventual disintegration of the Jena circle inevitable.

In Bamberg itself, however, Caroline’s recovery proceeded only slowly, and factors such as inclement weather similarly contributed to delaying the actual journey to Bocklet until mid-June. Schelling had in the meantime traveled to his visit his parents in Schorndorf, not returning until early July. On his arrival, however, he found that Auguste had come down ill with dysentery a few days earlier just as Caroline in her own turn had completely recovered. [12] A senior surgeon and midwife instructor by the name of Büchler was summoned from Bad Kissingen, though tension quickly developed between him and Schelling, the latter of whom was also involved in Auguste’s treatment. “From the very outset, I voiced a certain measure of distrust toward the person who had taken over Auguste’s medical treatement.” [13] Büchler remained optimistic concerning the eventual outcome of Auguste’s illness even up till two days before her death, an opinion Schelling was inclined to believe. As late as 6 July 1800, he wrote to Wilhelm Schlegel: “In a few days, however, she [Auguste] will probably have recovered to the point that we can return to Bamberg” (letter 265), a false estimation for which Schelling will later severely reproach himself, since Auguste’s condition in fact quickly deteriorated. Although an express messenger was dispatched to Bamberg to fetch Röschlaub, Auguste had already been dead several hours by the time he arrived. She died at fifteen years of age on 12 July 1800.

Immediately after her death, Büchler wholly blamed Schelling’s therapeutic intervention for the deadly outcome. Schelling, even according to his own testimony, was in such shock after Auguste’s death that he was unable to defend himself. It was only the arrival of Marcus and Wilhelm Schlegel that prompted Büchler to cease these accusations at least for a time. [14]

But not for long, since a few days later various prominent town citizens met with Büchler in the magistrate’s office of the neighboring village of Aschach, where in all probability the Würzburg theology professor Franz Berg was also present. [15] Here Büchler reiterated his accusations, suggesting as well that he had been coerced into not submitting his subsequent account of the illness for publication in the Journal der practischen Arzneykunde und Wundarzneykunst edited by Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland, Röschlaub’s grand adversary. |279| Marcus had indeed brought such about by convincing Büchler that publishing this account would only bring blame down upon Büchler himself. [16] This discussion in Aschach is of considerable significance insofar as two years later Franz Berg would publish a polemical piece turning those events in Bocklet into a public dispute.

Reactions to Auguste’s Death

The first reaction to Auguste’s death, of course, was profound grief. Wilhelm Schlegel wrote to Ludwig Tieck: “I will never cease to weep over this death. When I first received the news, I thought I would lose my mind.” [17] Auguste’s stepfather also attempted to lend his feelings expression in the cycle of poems Offerings for the Deceased. Schelling was plunged into a profound crisis, plagued by self-reproach to the point of considering suicide, [18] and it was not until two years later that he was able, in a letter to Wilhelm Schlegel, to speak about “the most painful event of my entire life.” [19] It was Ludwig Tieck’s brother, Friedrich Tieck, who in 1804 produced a bust of Auguste, and it was after the model of this bust that between 1811 and 1814 Bertel Thorvaldsen produced another bust and a memorial for the deceased.

These attestations notwithstanding, initial signs of discord and accusation were also already discernible. Friedrich von Hardenberg viewed the matter in connection with the mother’s objectionable lifestyle. “Heaven has now taken her in, since her mother abandoned her and her father surrendered her over. . . . One cannot keep such a child as easily as one does a lover. But now she is completely free.” [20] Auguste’s final letters, however, seem to contradict Hardenberg’s estimation here, giving the impression instead that the relationship between Schelling, Caroline, and Auguste was quite harmonious. Dorothea Veit made no secret of her view of things: “Only imagine, dear Auguste had to serve as an atonement sacrifice for so much guilt on the part of others.” [21] These remarks, based on her disapproval of the relationship between Caroline and Schelling, cannot but come as a surprise, revealing as they do a fundamental discrepancy between the Jena circle’s theory and praxis of morality. At the same time the circle’s members were castigating the hypocritical nature of moral laws in their publications, this alleged transgression of precisely those moral laws by a member of their own circle provoked criticism and rejection.

The dynamic we find at work in virtually every member of the circle — namely, that despite behavior in a manner contrary to bourgeois morality on the part of one of its members, nonetheless a friend’s similar behavior is condemned — demonstrates that their emotions are unable to do justice to the |280| rigorous conceptual implications of their own position . . . In this sense, the Schlegel circle, despite the considerable appearance of an intended and practiced épater le bourgeois, [22] is for all practical purposes merely a miniature copy of precisely the same society whose regnant laws these friends believe they are battling. [23]

Dorothea, moreover, was resolutely convinced of Schelling’s personal culpability in the outcome of Auguste’s illness, albeit without producing supporting arguments. “The Brownian arts are not to be reproached in this instance . . . and on top of that, Schelling meddled in the whole thing” [24] — an utterly self-contradictory statement, since Schelling had “meddled” exclusively according to the Brownian method.

Considerations from the Perspective of Medical History

in the Dispute between Schelling and Büchler Concerning Auguste’s Treatment

According to Schelling, the dispute initially arose because of the application of a tincture of rhubarb and of opium mixed with gummi arabicum. In his opinion, this addition to opium constitutes “a debilitative substance he [Büchler] had admixed with the opium because it would soften the body, make the bowels slippery, and all the other expressions one uses here,” [25] and thus a substance that is in fact contraindicated in such treatment just as is the tincture of rhubarb, that is, a laxative. Schelling therefore prescribed smaller doses of pure opium, something the apothecary, however, was not always able to deliver punctually. [26]

It seems appropriate at this point to discuss the background to this disputed medication in medical history. Büchler’s prescribed treatment of a twofold application of a laxative was theoretically grounded in humoral pathology, according to which illness was ultimately an expression of the deficient condition of various fluids, with “impurities” of various bodily fluids constituting the actual pathological substrate. In the case of infectious illnesses such as dysentery, a putrefaction of these fluids was believed to have occurred. Traditional treatment consisted in removing these rotten fluids, for example, by bloodletting, emetics, venesection, or, as in the present case, by means of purgatives. According to pathophysiological opinion today, however, such measures implemented in cases of dysentery would unfortunately worsen the diarrheal symptoms through laxatives and subject the patient to the life-threating danger of dehydration and severe electrolyte depletion. Röschlaub had already recognized the dangerous consequences of such evacuant treatment |281|: “It is only too true that each year large numbers of people become the victims of the most baseless humoral pathology.” [27]

Brownianism took completely different theoretical considerations as its point of departure. Brown defined the life of an organism with reference to its capacity to react to stimuli. This excitability (incitabilitas) is the fundamental characteristic distinguishing a living organism from inanimateness. Good health obtains as long as stimuli and excitability are in a harmonious relationship. Illness results from a disrupted relationship. A condition of excessive stimuli causes sthenia, one of insufficient stimuli asthenia. In cases of extreme stimuli, the organism reacts commensurately (ultimate excitement) such that its excitability becomes exhausted, leading to a “dialectical” condition, namely, indirect asthenia. The other extreme, namely, the withdrawal of all vitally necessary stimuli, leads to direct weakness. Both extremes constitute mortal danger.

The therapeutic consequences deriving from this theory constituted a fundamental change. According to Brown, the weakening measures traditionally applied in the majority of cases, such as bloodletting, purgatives, clysters, or emetics, were indicated only in the rare cases of sthenic illness. Instead, the considerably more frequent asthenic illnesses were treated with fortifiers such as nourishing food, warmth, or opiates.

Schelling’s intervention in the case of Auguste Böhmer becomes more comprehensible against this background. Any weakening, purgative, or aesthenitive treatment is contraindicated in the case of an illness involving weakness. According to Brown’s view, dysentery was to be treated with fortifiers such as opiates without the disputed admixture, and never with purgative or weakening remedies. “In purely general, asthenic illnesses, the theory of excitability virtually prohibits any application of remedies that cause a loosening or purging of the bowels.” [28] The tincture of rhubarb and admixture of gummi arabicum recommended by Büchler — which, as Kobert maintains, accomplishes nothing apart from “itself provoking mucus secretion and prompting excessive diarrhea [29] — is contraindicated in the Brownian system. Viewed from this perspective, the distinction between traditional treatment and the Brownian understanding is illustrated in an exemplary fashion in the case of Auguste Böhmer’s illness.

In this context, it is also helpful to consider the politics of class in Germany as such applied to Brownianism at the time. By far most |282| of the medical treatment available to the population at large was in the hands of exclusively empirically trained, guild-associated barbers and surgeons over against a minority of academically trained physicians who did not deal with illnesses normally treated by “chirurgeons.”

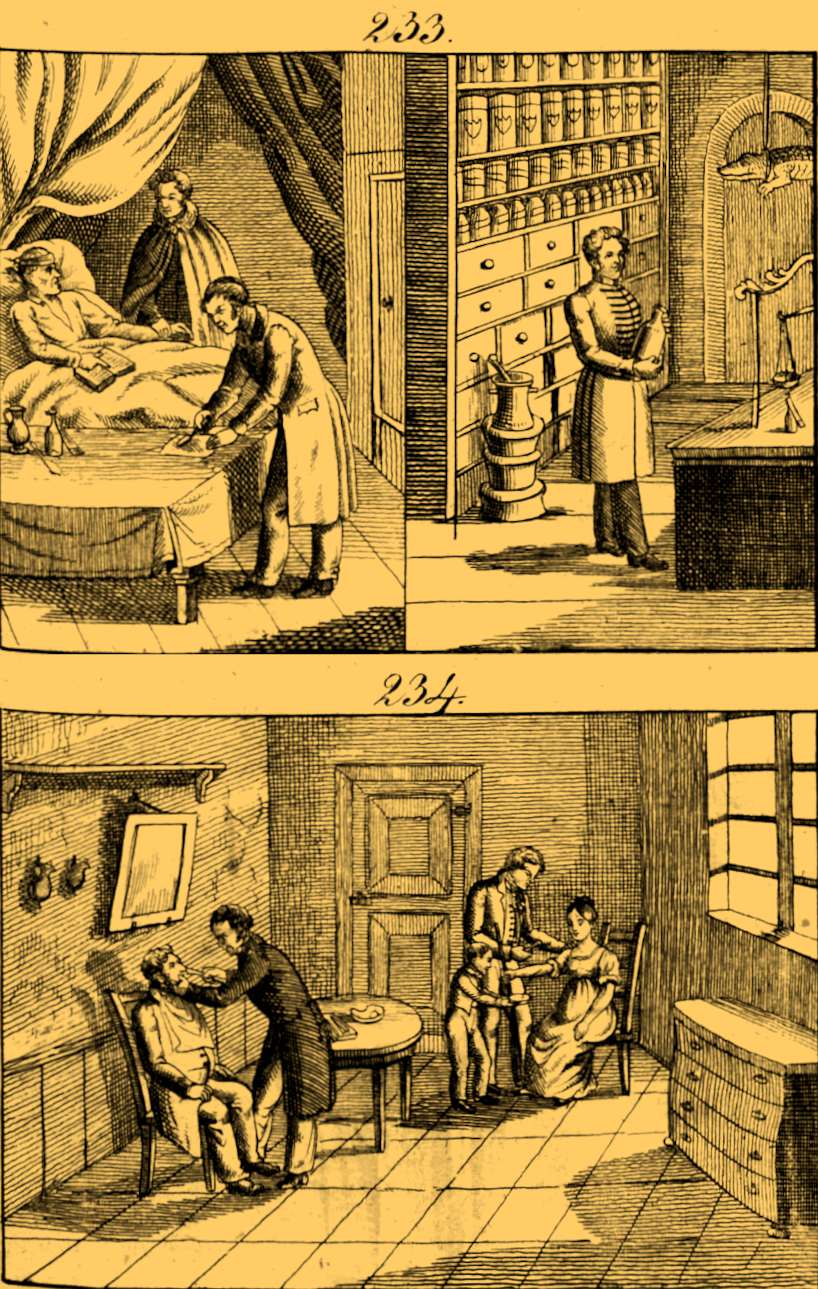

[Ed. note: representative illustrations of [1] the traditional surgeon and [2] the emergent, university-trained physician (Schauplatz der Natur und der Künste, vol. 4 [Vienna 1776], plates 36, 37):]

Röschlaub vehemently advocated consolidating the fields of surgery and internal medicine in the hands of university-trained physicians, a provocative and explosive demand whose implementation would have meant unemployment for the majority of traditional healthcare professionals, professionals for whom Brownianism thus represented an existential threat. These two aspects — the exemplary distinction with respect to treatment and the background of class politics — are indispensable for a proper historical understanding of the ensuing dispute.

[Ed. note: by the 1830s, the distinction was still being made between the university-trained physician, on the one hand (shown here on the left in plate 233; on the right: the apothecary], and, on plate 234, the surgeon or “chirurgeon,” on the other (J. E. Gailer, Neuer Orbis pictus für die Jugend: oder Schauplatz der Natur, der Kunst und des Menschenlebens [Reutlingen 1832], plates 233, 234):]

The Public Attack Against Schelling

Public discussion of Auguste’s death was triggered two years later by the anonymously published piece Encomium for the Most Recent Philosophy by the Würzburg theologian Franz Berg (n.p. [Nürnberg] 1802). On 6 October 1801, the Bamberg prince bishop, Christoph Franz von Buseck, by way of his nephew and coadjutor Georg Karl Ignaz von Fechenbach, had commissioned Berg with producing a satire. Although Röschlaub had dedicated the first volume of his Pathogenie (1798) to the prince bishop, [30] this show of respect changed nothing with respect to the latter’s critical view of the medical faculty. The target of the attack initiated by the prince bishop was to be the disputed doctoral theses of Joseph Reubel at the Bamberg University under the direction of Georg Nüsslein:

While reading through these theses, His Gracious Excellency the Prince recalled quite vividly what we had read a while back in the The Hyperborean Ass about similar philosophical nonsense. Insofar as we have for some time now taken an interest in the direction taken by university studies in Bamberg, and with regret can see from these theses how young people’s minds are being turned askew, we would like for the ecclesiastical Rath and professor Berg to review these theses in the Würzburger gelehrte Anzeigen such that the Bamberg professor feels the merited scourge of satire in as emphatic a fashion as possible. [31]

The Hyperborean Ass mentioned by the prince bishop is a polemic by August von Kotzebue against the Romantics that strings together fragments from Friedrich Schlegel’s Lucinde and the two brothers’ Athenaeum in a way distorting their meaning. |283| Kotzebue, who also otherwise had taken a position of open hostility toward the Romantics, will also use this dispute concerning Auguste’s death in his periodical Der Freimüthige 24 (1803). [32]

Berg’s instructions from the bishop were thus to compose a satire against the alleged danger of “young people’s minds in Bamberg . . . being turned askew.” Yet even though the person primarily responsible for the disputed doctoral theses was Georg Nüsslein, and even though Röschlaub as well had come out against them, [33] Berg went far beyond this initiative, and his review turned into an independent publication. By way of his criticism of Nüsslein, he polemicized as well against the protagonists of such “philosophical nonsense,” namely, Schelling and Röschlaub and the “transcendental epoch” in medicine they had initiated. [34] They, so Berg, were responsible for the “philosophical Saint Vitus Dance” raging epidemically at various universities [35] and for “autotheism” to which so many students had fallen prey: [36] “Only behold these ego’s-gods that are now sprouting up at our universities like mushrooms.” [37] Although only a single sentence refers to the events in Bocklet, that sentence would function to set the entire subsequent dispute into motion:

Except may heaven forbid that he [Reubel] suffer the misfortune of killing in reality those whom he heals in ideality, a misfortune that befell Schelling, the One and Only, in Bocklet in Franconia in the case of M[ademoiselle] B[öhmer], as malicious people maintain. [38]

The response to Berg’s polemic was swift, similarly anonymous, and no less disrespectful, namely, Lob der Cranioscopie: Ein Gegenstück zum Lobe der allerneusten Philosophie (Praise for cranioscopy [here: phrenology]: a counterpart to praise for the most recent philosophy) (n.p. 1802). Johann Baptist Schwab [39] suspected that the author was either Adalbert Friedrich Marcus or Ignaz Döllinger, who as a member of the Bamberg faculty might similarly have felt attacked. Picking up on the phrenology of Franz Joseph Gall, a satirical explanation is offered for why “the vain, obsessed being . . . like a tiny, fire-spitting Berg [Germ.: mountain], nonetheless still insisted on discharging its stinking sulfurous vapors.” [40] In his own response in the Würzburger gelehrte Anzeigen, Berg refers to this publication as being “quite in line with the most recent philosophical terrorism.” [41]

Schelling’s Appointment in Würzburg in 1803

Franz Berg’s polemic at the initiative of the Bamberg prince bishop von Buseck was also set against a political background that would come to bear a bit later and in which the opposing parties were in fact identical. To wit, his piece can also be understood as an attempt to discredit |284| “modern” philosophy, since, after all, the “modern” age was certainly threatening the prince bishop himself through secularization. [42] And indeed, the altered territorial configuration following the Final Recess of the Reichsdeputation (Reichsdeputationshauptschluss; also known as the Principal Conclusion of the Extraordinary Imperial Delegation) in 1803, as a result of which Würzburg and Bamberg both were ceded to Bavaria, along with the process of secularization accompanying the dissolution of the Old Empire, were determinative factors contributing to Schelling’s appointment in Würzburg. For Christian Gottfried Schütz — along with his Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung — was also among the applicants, supported by Franz Berg, involved in the tedious negotiations in connection with which Marcus functioned as Schelling’s advocate, engaging the entire breadth of his own influence to prevent the appointment of the other Jena applicants: “The time has come to destroy the nest that these gentlemen from Jena are intent on constructing in Franconia for the sake of brooding their rotten eggs there.” [43] After Schelling had paid a personal visit to Munich, the decision was made to offer him an appointment, the reform-minded administration under the minister Maximilian von Montgelas wanting to establish a second university in Würzburg (after Landshut) that would not be subject to ecclesiastical influence, and viewing Schelling as a persuasive representative of the new philosophy.

In 1804 Franz Berg, who was now Schelling’s university colleague, would again take issue with Schelling in print with his Sextus oder über die absolute Erkenntnis bei Schelling (Sextus, or: on absolute knowledge in Schelling), albeit now with a more moderate tone (“I do value Schelling, but I value truth more than him”) [44] and now using a considerably less disrespectful vocabulary. This publication served as a cornerstone among many others amid the increasing opposition to Schelling that ultimately prompted him to leave Würzburg in 1806.

The Dispute with the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung

But back to the events of 1802. Franz Berg’s Lob der allerneuesten Philosophie was reviewed in the Würzburger gelehrte Anzeigen (1802, no. 26), in the Oberdeutsche Literaturzeitung (1802, no. 49), and in the Leipziger Literaturzeitung (1802, no. 225). [45] A reaction from those who were actually attacked, however, was provoked only in connection with a review in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (1802, no. 225), which even earlier had already criticized other doctoral theses in Bamberg and accused the faculty there of “scholarly and moral nonsense.” [46] According to this review, Reubel’s propositions contained “such a wealth of genuine, purified philosophical gold, cleansed of all the slag of common human understanding,” [47] that the reviewer finds himself prompted to provide an unabridged rendering of Berg’s own polemic, recommending to Herr Reubel, moreover, “that the latter might form a triumvirate together with Röschlaub and Schelling |285| for dispelling death.” He then quotes word-for-word the single sentence (cited above) referring to the death of Auguste Böhmer.

Schelling, who became aware of Berg’s publication only through this review in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, was profoundly indignant. He informed Wilhelm Schlegel, who similarly felt himself to have been the target of the most vile defamation. An extensive correspondence between the two was now set into motion with the goal of stepping forward together to oppose this attack “and finish Schütz off.” [48]

Wilhelm Schlegel demanded in Schelling’s name that Schütz, as the editor of the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, remove this review, publish another in its place, and print a public apology. All that appeared, however, was a reference in the Intelligenzblatt of the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung on 25 September 1802, signed anonymously by “the reviewer,” to the effect that the quotation was in any case merely the faithful rendering of a particular passage, and, moreover, merely something “malicious people said” rather than an assertion that Schelling caused the death.

Of course, this evasion by way of reference to the merely formal structure of a text and the nature of the statement as a mere quote could not satisfy those who were thus put off. After an arrangement with Schelling and at the latter’s cost, Wilhelm Schlegel published the rejoinder An das Publicum: Rüge einer in der Jenaischen Allg. Literatur-Zeitung begangnen Ehrenschändung (Tübingen 1802), [49] in which he once more summarized the course of events surrounding the review and the accusations against Schütz, and then tried to demonstrate Schelling’s innocence. In addition to Röschlaub’s personal communication that Auguste “died of a convergence of two maladies, either of which alone would have sufficed to bring about her death,” he also provided written statements from both Röschlaub and Marcus, who similarly attested Schelling’s innocence with respect to the tragic conclusion to those events. Unfortunately, the entirety of Röschlaub’s personal communication is not provided, neither in the written statement nor elsewhere. That notwithstanding, among all the pieces published in connection with this dispute, Wilhelm Schlegel’s argument seems the most objective and least overtly polemic.

Goethe, too, was kept informed of these events, and Schelling was hoping to bring his authority to bear on the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung. Goethe, however, maintained a reserved posture, though he did come to appreciate Schelling’s position and discussed the affair with him. “The personal weight of Goethe could have little effect . . . to the contrary, Goethe would only thereby have exposed himself.” [50] Goethe’s reserve, among other factors, prompted Schelling to abandon the idea of pursuing legal action against Schütz for defamation.

|286| Schütz by no means let the attacks leveled by Schlegel’s publication go unanswered, responding instead with his Species facti nebst Actenstuecken zum Beweise daß Hr. Rath August Wilh. Schlegel mit seiner Rüge, worinnen er der Allgem. Lit. Zeitung eine begangne Ehrenschändung fälschlich aufbürdet, niemanden als sich selbst beschimpft habe (Jena, Leipzig 1803). Although this publication was accompanied by an addendum, Nebst einem Anhange über das Benehmen des Schellingschen Obscurantismus — an allusion to Schelling’s attack on the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung in his Neue Zeitschrift für speculative Physik — its title sufficiently demonstrates that Schütz was no longer focusing on the real issue, namely, the death of Auguste Böhmer. [51] Instead, he was now concerned with denigrating Schelling’s and Schlegel’s lifestyle and philosophy and with reviving once more their earlier dispute with the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung along with the attendant feud, and certainly with portraying these events to his own advantage. The publication, moreover, is full of polemical attacks and passing shots at Schelling, Schlegel, and Röschlaub. With malicious reference to the relationship between Caroline and Schelling, he asks Wilhelm Schlegel “why precisely you, of all people, are seeking to represent Herr Professor Schelling in this matter — who, being of age, is certainly capable of doing so himself — unless, of course, it be that he has already represented you in a different capacity.” [52]

During this phase, the dispute concerning the death of Auguste Böhmer seemed to outsiders to be an equally incomprehensible and self-propelling sequence of polemic, justification, and feuds. Because the events in Bocklet now seemed to function solely as a welcome occasion to continue old conflicts, an examination of the origins and triggering arguments of this conflict is helpful, some of which predate Auguste’s death.

The initial dispute between Schelling and Schütz involved two reviews of Schelling’s Ideen zu einer Philosophie der Natur, [53] both of which Schelling rejected as being wholly inferior and insufficient. [54] He would accept, moreover, only Henrik Steffens as the appropriate reviewer for his Entwurf der Naturphilosophie. [55] Schütz, of course, rejected such editorial patronization, whereupon Schelling felt obliged to publish a thorough presentation of events in his Zeitschrift für spekulative Physik, a presentation he published independently as well. [56] Schütz responded at length in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, [57] and even the addendum, Über das Benehmen des Obscurantismus in the piece contra Wilhelm Schlegel from 1803 is in part referring to these quarrels.

Shortly after these initial tensions between Schelling and Schütz, the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung published a declaration from Wilhelm Schlegel on 13 November 1799 in which he notified the public of his withdrawal from his previously extensive contributions to the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, since in his opinion several reviews “clearly betray a desire |287| to set criticism back thirty years.” [58] The immediate occasion was the review of Friedrich Nicolai’s novel Vertraute Briefe von Adelheid B** an ihre Freundin Julie S*** (Berlin, Stettin 1799), which with rare and unequivocal clarity adduces many of the more substantive arguments contra the Romantics and which Wilhelm Schlegel could not but understand as an allusion to himself and the Jena circle. [59]

Those who have had the opportunity to see and become annoyed by the exclusive wisdom of various young philosophers, by their scholarly egoism and arrogant disregard for civil circumstances and customs, in a word: by the signs of the times — will, while reading this novel, praise the satirist who was able to focus so sharply on these things and castigate this foolishness with such wit and humor.

The essence of this novel, namely, the reeducation, by his steady sister-in-law, of a young man who has run aground as a result of the new philosophy, similarly provides an exemplary parade of the virtues and values the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung felt called to defend and preserve against the “signs of the times” in the year 1799.

Indeed, she resolves to improve him. The stepwise progression of her efforts is described with considerable subtlety, how she first improves his handsome external appearance, then introduces him to society to make him more humane, then awakens in him a longing for specific activities, and finally also prompts him to find satisfaction in bourgeois activities. The mere idea of having a noble woman set such a distorted person aright is an excellent one.

The scope of this dispute between Schütz and the Romantics far transcended a mere exchange of arguments and polemic, culminating instead in a defamation suit as a result of which Schelling was fined 10, Schütz 5 Taler. [60] On a personal level, too, the quarrelling parties distanced themselves contemptuously from one another. At Schütz’s home, for example, essays contra the Schlegel brothers were read aloud as entertainment prior to theater performances. [61]

This dispute concerning Auguste Böhmer’s death coincided with a previously existing confrontation between two camps, and it is only through the specific focus of the various arguments presented at the beginning of the dispute and the self-understanding of its participants that the sequence of presentations and counter-presentations between the Romantics and the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung acquires contours. Rudolf Haym summarized the factors triggering these quarrels as follows: [62]

After Fichte had been labeled an atheist, and Wilhelm Schlegel and his brother had erected a completely different standard in Athenaeum, the feeling [on the part of the editors of the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung] was that they must not allow themselves to be nudged any further to the left, since not only was a disposition this radical incommensurate with the moderate spirit of mediation the editors were trying to maintain, it also seem quite inadvisable to endanger the periodical’s circulation numbers by alienating the taste of the average scholarly public.

|288|

Parallels to the Atheism Dispute

In his assessment, Haym similarly focuses on the atheism dispute surrounding Fichte as one of the central points of departure. Alongside its acknowledged significance in this sense, however, further parallels emerge between Fichte’s dismissal in Jena and the aftermath of Auguste Böhmer’s death. The anonymous publications that triggered the two scandals were printed in the same bookstore, namely, “Nürnberg bei Felseckers Söhnen.” [63] Similarly, in both cases the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung became an unequivocally partisan participant through its published reports. On the one hand, it was the tendentious review of the Lob der allerneuesten Philosophie that ignited public discussion of Auguste’s death; on the other, it was through its distorted portrayal that the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung stabbed Fichte in the back in his own dispute with the authorities.

Friedrich Karl Forberg had published an essay in the Philosophisches Journal — “Entwicklung des Begriffes der Religion” — that Fichte, sensing, in his capacity as editor, the potential for strife, complemented with his own essay, “Über den Grund unseres Glaubens an die göttliche Weltregierung.” [64] It was through the anonymous publication mentioned above that the essays by both Fichte and Forberg became the focus of a public dispute because of the theological positions they represented. In a private letter to Christian Gottlob Voigt, Fichte threatened to leave Jena should he be subjected to an official rebuke. Quite contrary to Fichte’s own wishes, Voigt passed this private letter along to the duke, Karl August, who viewed the statement as a request for dismissal and responded by granting it. The Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung immediately published a commentary in which it presented these events from the perspective of the duke, maintaining that the dismissal was “merely the consequence of his [Fichte’s] own declaration,” [65] a statement with which the editors essentially confirmed what was in fact a false rumor, namely, that Fichte had indeed officially requested his own dismissal.

Other considerations also suggest that the quarreling parties were quite similarly juxtaposed in both the atheism dispute and Auguste Böhmer’s death. Whereas the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung attacked Fichte behind his back, Schelling displayed his solidarity with Fichte. “Schelling has behaved nobly on my behalf . . . The jurist Hufeland and Schütz feebly and in part vilely,” Fichte remarked. [66] Röschlaub, too, took Fichte’s side, dedicating to him in April 1799 the second volume of his Magazin zur Vervollkommnung der theoretischen und praktischen Heilkunde with an unmistakable reference |289| to the atheism dispute, and remarking unequivocally in his foreword that he, too, was unfortunately anticipating assessments of his own medical system that were equally false and incompetent “as, for example, the assessment published in the name of the Electoral Saxon commission concerning several essays in your [Fichte’s] Philosophisches Journal” (p. vi). After Fichte’s dismissal, Schelling suggested Bamberg as a refuge: “Politically you doubtless have nothing to worry about in Bamberg. Röschlaub has some influence among the ministers.” [67] Although Fichte’s response is unknown, he in any case remained in Berlin. These parallels to the atheism dispute also demonstrate that Auguste Böhmer’s death became a point of contention within a previously existing constellation.

The Events in Bocklet in Historiography

Over the course of time, portrayals of the events in Bocklet became increasingly florid and ornate. In 1817, Georg Michael Weber revisited the story under the pseudonym Antibarbarius Labienus, this time with imaginative names and the copious attendant rumors. Schelling is described as a “hierophant created as a physician purely a priori from energy and because of his idealist natural science.” [68] Alongside an attack on him, it was again his relationship with Auguste and Caroline that provided the target of polemic. “He [Schelling] was to be most pitied, having forfeited possession of beautiful Aglaje [Auguste] and finding himself forced . . . to throw himself into the arms of the fat mother, Cybele [Caroline]. [69] In 1879, the entire affair was for Johannes Janssen ultimately an expression of a scandalous decay of morals. “After marrying Schlegel, it was two years before Caroline’s ‘cult of free love’ again found the ‘right one,’ namely, the philosopher Schelling.” [70] Such was the case, Janssen explained, because although Caroline had originally designated Schelling for Auguste, “Auguste’s unexpectedly sudden death in July 1800 disrupted these plans and — nowhere does the Lady of Culture appear more repugnant than here — we now see step by step how the undutiful woman seduces the characterless philosopher into her net.” [71] Fuhrmans (1962), however, considers the rumor Janssen is here propagating, namely, that Caroline had actually designated Auguste to be Schelling’s wife, to be equally unfounded and false.

Hans Jörg Sandkühler seems to characterize accurately the aftereffects of the events in Bocklet when he writes in summary: “Schelling bitterly defended himself against these accusations, and yet — semper quid haeret. [72]

|290|

The Dispute within the Social Framework of Romanticism

As the previous presentation of events has shown, the death of Auguste Böhmer and the subsequent disputes invariably appeared in connection with other incidents, and never free from polemic. Only within the milieu through which the death of a young girl could turn into a scandal can one understand this affair historically, and to the extent one understands the story not merely as the chronicle of a scandal, one should certainly also examine its historical significance.

The social constellation of this dispute — a situation that seems to typify and simultaneously handicap any political evaluation of Romanticism — obtained for but an extremely brief period. As early as 1806, when Schelling left Würzburg, his position on the faculty, his relationship with Röschlaub and with Brownianism, as well as the influence of this particular medical system at large had all changed. [73]

Three thematic focal points are discernible: literary Romanticism, post-Kantian philosophy, and Brownianism, represented by Wilhelm Schlegel, Schelling, and Röschlaub. Those engaged in polemical over-simplification construed these points and representatives as a unity by way of the comprehensive epithet “scientific, scholarly, and moral nonsense.” Since in this context the terms “scientific, scholarly,” and “philosophical” were essentially understood synonymously, the defamed group associated with the scandal surrounding Auguste Böhmer’s death symbolized the community of those intent on breaking with tradition. The maliciousness attaching to these accusations derives from their insistence on identifying this group and its ideas with the death of a young girl.

Literary Romanticism has been the subject of extremely broad and comprehensive scholarly examination, albeit ultimately without any consensus having emerged. “The scholarly understanding of Romanticism during our century is characterized by the most heterogeneous approaches and the most contradictory assessments.” [74] Schelling’s philosophy of nature is similarly quite present in contemporary discussion. [75] Things stand quite differently with Brownianism. Although for a short period around the turn of the century it enjoyed strong resonance, even pushing aside established medicine for a time, its historiographical assessment — if it has undergone such at all — has been almost exclusively negative apart from some somewhat more differentiated recent opinions. [76] Even though fundamental therapeutic changes, for example, the abandonment of exclusively purgative and evacuative treatments, continued to endure, the historical fate of this system, a system |291| whose significance Schelling once compared to that of Kant’s philosophy, remains an unresolved question today. [77] The scandal generated by the death of Auguste Böhmer offers points of reference for what will invariably be complex, multilayered assessments.

Concerning the events themselves: One can no longer ascertain with any certainty the extent to which accusations are justified that Schelling caused Auguste’s death through inappropriate intervention. Quite apart from the general difficulties attaching to any such causal queries, information pertaining to this particular case is inadequate in any case. Especially the full content of Röschlaub’s assertion cited by Wilhelm Schlegel can no longer be ascertained, namely, that Auguste in fact suffered from two extremely serious illnesses. That said, if Schelling did indeed merely order that the administration of two purgatives be stopped and that the opium dose be reduced, then according to contemporary pathophysiology he in all probability influenced Auguste’s illness positively by helping to thwart the serious and clearly deleterious effects of purgative (evacuant) treatments.

Concerning the aftermath of the events: What began with mutual accusations within a Jena circle at odds with itself acquired increasingly broad dimensions; these accusations, moreover, allow certain conclusions concerning the circle’s inner structure. The adversaries changed, however, once the public debate ignited two years later, and the spectrum of accusations was broadened into a comprehensive attack, the antagonists now including Franz Berg at the initiative of the Bamberg bishop, and Christian Gottfried Schütz with his influential review periodical, the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung. Rather than dealing primarily with the concrete medical evidence and events in Bocklet, however, the two publications focused instead on a general criticism of philosophy, lifestyle, and Brownianism.

The scope and intensity of the accusations and the embittered vehemence of the debate itself can be understood as a conflict between rival social groups. Those who were the object of these attacks represented philosophical and medical positions, with all the attendant social implications, that were as relevant as those of their adversaries; that is, they were not merely contentious individuals. Several factors support this assertion. For a time, both Röschlaub and Schelling enjoyed considerable popularity among students, which indeed was one reason they had received appointments in the first place. Both similarly enjoyed a certain measure of support from the administration in Munich, and the faculty in Landshut similarly was on their side, even bestowing an honorary medical doctorate on Schelling. For Schelling’s adversaries, of course, this honorific distinction constituted a brazen provocation, representing as it did for them little more than cronyism between Röschlaub and Schelling. Those adversaries were, moreover, utterly convinced of this “a priori doctor’s” culpability in the death of Auguste Böhmer. That notwithstanding, the accusation of favoritism for Schelling by way of Röschlaub does not really correspond to the facts, since the resolution to bestow the honorary doctorate was unanimously accepted by the |292| faculty in Landshut, and Röschlaub himself, reporting the news of this honor to Schelling, remarks that the idea did not derive from him in any case, being instead a wish “voiced by my colleagues even before my own arrival.” [78]

The dispute concerning Auguste Böhmer’s death as a feud contra new ideas in medicine, literature, and philosophy picked up on three previous, ongoing conflicts. First, on the withdrawal of both Wilhelm Schlegel and Schelling as contributors to the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung. The disposition of argumentation can be articulated in terms of certain temporal metaphors that at once also betray the self-understanding of the parties involved. While the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung tried to oppose the intolerable “signs of the times,” Wilhelm Schlegel feared that criticism would be set back “thirty years.” Romantic literature and post-Kantian philosophy understood themselves as that which was “new,” and their adversaries as “behind the times,” such as “Herr Schütz, who has never been able to elevate himself above the merely memorized letter of Kantian philosophy.” [79]

The second point was Fichte’s dismissal in the wake of the atheism dispute. Here, too, the same parties emerged. Alongside substantive criticism of Fichte’s pantheistic understanding of God, this dispute now also acquired a political note. “Of course, as Fichte doubtless knew, behind the accusation of atheism lurked the very concrete suspicion of the nontransparent heresy of subversive democratic intrigues, a suspicion similarly fostering mistrust against ‘independent thinking’ as the ‘source of all bourgeois disquiet.'” [80]

The third and final point involved the disputed doctoral theses at the university in Bamberg, which functioned as an excuse both for the bishop and for the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung to launch polemics against “scientific, scholarly, and moral nonsense” in the stronghold of Brownianism in Germany. And indeed, Reubel’s theses do seem nonsensical, glibly abbreviated, and incomprehensible, nor were they without opponents even among the Bamberg faculty, though this polemic does portray the actual circumstances quite well. Röschlaub, convinced that the theses were untenable, tried to protest but was met by Marcus’s resistance, who expressed his lack of understanding of Röschlaub’s position as late as 1813: “At the time you seemed to me to have been hitherto dressed in a quite worldly fashion, and then, suddenly, once again put on a monk’s habit. Toward poor Reubel . . . you behaved like a Dominican monk recently arrived from Spain. [81] And not least, it was these disputed doctoral theses that induced Röschlaub to remark that “it was not the opponents alone who discredited Brown’s teachings among the ill-informed, but rather even many of its alleged friends, patrons, and followers.” [82]

|293| Criticism of these doctoral theses, however, like the entire dispute concerning Auguste Böhmer, seems merely to have functioned as a welcome occasion to launch attacks against the real enemy, namely, Brownianism in its German variant. The alliance between the “speculative” philosophy of nature and medicine, a direction Berg disqualified as a “transcendental epoch,” did indeed contain considerable “concrete” potential for initiating change, since this medical system threatened with radical change not only the theoretical basis of medicine, but also therapeutic praxis as such as well as the structure and organization of the health professions at large.

What initially appeared to be a tragic incident and its consequences proved to be an occasion for significant positional struggles within a turbulent, complex age. The result was that this medical scandal hardened the adversarial fronts and heightened the previously existing controversy surrounding Brownianism. Ultimately the polemic concerning Auguste Böhmer’s death undermined attempts at reforming medicine.

Notes

[*] Original: “Der Tod der Auguste Böhmer. Chronik eines medizinischen Skandals, seine Hintergründe und seine historische Bedeutung,” History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 11 (1989) 275–95. Pagination in the text refers to the original article. — Translated with the kind permission of the author, Urban Wiesing, and the editor of the History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, Staffan Müller-Wille. Urban Wiesing is director of the Institute for Ethics and the History of Medicine at the Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen.

English abstract:

When fifteen-year-old Auguste Böhmer, daughter of Caroline Schlegel and stepdaughter of Wilhelm Schlegel, died on 12 July 1800, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling was accused of being responsible for this tragic event after trying to treat her according to the medical system of John Brown.

The ensuing scandal became a symbol of the danger inherent in every progressive movement of that time: Romantic literature, Schelling’s philosophy of nature, and Brownianism in its German version as represented by Andreas Röschlaub. An attempt is made to analyse the social and political background of the scandal and to understand its historical significance as a fight against a fundamental reform of medicine. Back.

[1] [Translator’s note: Elsewhere in this project, the term “Brunonianism” is used, being the term commonly used in England during the late-eighteenth century at least by some of John Brown’s followers (see the supplementary appendix on “Of the Brunonian Doctrine”). In this present essay, the term “Brownianism” is used commensurate with common modern usage.] Back.

[2] Ideen zu einer Philosophie der Natur (Leipzig 1797), Von der Weltseele (Hamburg 1798), Erster Entwurf eines Systems der Naturphilosophie (Leipzig 1799), and System des transzendentalen Idealismus (Tübingen 1800). Back.

[3] K. E. Rothschuh, “Naturphilosophische Konzepte der Medizin aus der deutschen Romantik,” in Romantik in Deutschland. Ein interdisziplinäres Symposion (Stuttgart 1978), 243–66, here 244. Back.

[4] Schelling, “Anhang zu dem voranstehenden Aufsatz, betreffend zwei naturphilosophische Recensionen und die Jenaische Allgemeine Literaturzeitung vom Herausgeber,” Zeitschrift für spekulative Physik, ed. F. W. J. Schelling, vol. 1, no. 1 (Jena, Leipzig 1800), 49–99, here 81. Back.

[5] An das Publicum. Rüge einer in der Jenaischen Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung begangnen Ehrenschändung (Tübingen 1802), 14; trans. To the Public. Rebuke of a Defamation of Honor Perpetrated in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (letter/document 371b). Back.

[6] Friedrich Schlegel to Friedrich von Hardenberg in mid-September 1797 (letter 185a). Back.

[7] See Inge Hoffman-Axthelm, “Geisterfamilie.” Studien zur Geselligkeit der Frühromantik (Frankfurt 1973). Back.

[9] Ibid. Back.

[10] See Nelly Tsouyopoulos, “Reformen am Bamberger Krankenhaus — Theorie und Praxis der Medizin um 1800,” in Historia Hospitalium (Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Krankenhausgeschichte) 11 (1976), 103–22; idem, Andreas Röschlaub und die Romantische Medizin. Die philosophischen Grundlagen der modernen Medizin (Stuttgart, New York 1982). Back.

[11] Dorothea to Schleiermacher on 15 May 1800 (letter 259s). Back.

[12] Schelling to Wilhelm Schlegel on 6 July 1800 (letter 265). Back.

[13] Schelling to Wilhelm Schlegel on 3 September 1802 (letter 369d). Back.

[14] Schelling to Wilhelm Schlegel on 3 September 1802 (letter 369d). Back.

[15] Attested in Christian Gottfried Schütz, Species facti nebst Actenstuecken zum Beweise dass Hr. Rath August Wilh. Schlegel der Zeit in Berlin mit seiner Ruege, worinnen er der Allgem. Lit. Zeitung eine begangne Ehrenschändung fälschlich aufbürdet, niemanden als sich selbst beschimpft habe / von C. G. Schuetz. Nebst einem Anhange über das Benehmen des Schellingischen Obscurantismus (“Species facti [the particular character or peculiar circumstances of the thing done; the particular criminal act charged against a person] along with documents proving that Herr Rath Schlegel, currently residing in Berlin, has rebuked no one but himself with his Rebuke, in which he falsely accuses the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung of having committed a defamation of honor / by C. G. Schuetz. With an addendum concerning the comportment of Schellingian obscurantism”) (Jena, Leipzig 1803), 25. Back.

[16] Wilhelm Schlegel to Schelling on 27 August 1802 (letter 369b). Back.

[17] Wilhelm Schlegel to Ludwig Tieck on 14 September 1800 (letter 267e). See also Fichte’s letter to Wilhelm Schlegel on 6 September 1800 (letter 267c). Back.

[18] Gisela Dischner, Caroline und der Jenaer Kreis. Ein Leben zwischen bürgerlicher Vereinzelung und romantischer Geselligkeit (Berlin 1979), 155. Back.

[19] Schelling to Wilhelm Schlegel on 3 September 1802 (letter 369d). Back.

[20] Friedrich von Hardenberg to Friedrich Schlegel on 28 July 1800 (letter 265h). Back.

[21] Dorothea Veit to Schleiermacher on 28 July 1800 (letter 265i). Back.

[22] [Translator’s note: Fr., “to amaze, dumbfound, flabbergast the bourgeois.”] Back.

[23] Inge Hoffmann-Axthelm, “Geisterfamilie.” Studien zur Geselligkeit der Frühromantik (Frankfurt am Main 1973), 202–3. Back.

[24] Dorothea Veit to Schleiermacher on 22 August 1800 (letter 266a). Back.

[25] Schelling to Wilhelm Schlegel on 3 September 1802 (letter 369d). Back.

[26] Wilhelm Schlegel to Schelling on 27 August 1802 (letter 369b); Schelling to Wilhelm Schlegel on 3 September 1802 (letter 369d). Back.

[27] Andreas Röschlaub and Georg Oeggl, “Ueber die sogennanten Vorbauungscuren,” Hygiea: Zeitschrift für öffentliche und private Gesundheitspflege 2 (1804), 168–215, here 209. Back.

[28] Andreas Röschlaub, “Ueber die Stuhlverhaltung in asthenischen Krankheiten,” in Magazin zur Vervollkommnung der theoretischen und praktischen Heilkunde 4 (1800) no. 1, 261–91, here 264. Back.

[29] Rudolf Kobert, Compendium der Arzneiverordnungslehre für Studirende und Ärzte, 2nd ed. (Stuttgart 1893), 109. Back.

[30] Andreas Röschlaub, Untersuchungen über Pathogenie oder Einleitung in die medizinische Theorie, 3 vols. (Frankfurt am Main 1798–1800). Back.

[31] Handschriftenabteilung der Universitätsbibliothek Würzburg, Nachlaass [literary estate] Franz Berg, M.ch.q. 334/13, no. 181. Back.

[32] See Wilhelm Porstner, “Der Freimüthige (1803–1806) im Kampf gegen Goethe und die Romantik,” diss., Vienna, 1930; Urban Wiesing, “Der Dichter, die Posse und die Erregbarkeit: August von Kotzebue und der Brownianismus,” Medizinhistorisches Journal 25, nos. 3/4 (1990) 234–51. Back.

[33] Nelly Tsouyopoulos, Andreas Röschlaub und die Romantische Medizin: Die philosophischen Grundlagen der modernen Medizin (Stuttgart, New York 1982). Back.

[34] Franz Berg, Lob der allerneuesten Philosophie (n.p. [Nürnberg] 1802), 21. Back.

[35] Ibid., 24. Back.

[36] Ibid., 18. Back.

[37] Ibid. Back.

[38] Ibid., 29. Back.

[39] Johann Baptist Schwab, Franz Berg an der Universität Würzburg (Würzburg 1869). Back.

[40] Anonymous, Lob der Cranioscopie: Ein Gegenstück zum Lobe der allerneusten Philosophie (n.p. 1802), 2. Back.

[41] Würzburger gelehrte Anzeigen (1802), Beilage 19, p. 20. Back.

[42] [Translator’s note: i.e., in the context of mediatization within the dissolution of the Old Empire (Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation).] Back.

[43] Adalbert Friedrich Marcus to Schelling on 1 August 1803 (letter 380c). Back.

[44] Franz Berg, Sextus oder über die absolute Erkenntnis bei Schelling: Ein Gespräch (Würzburg 1804), ii, in the introduction, dated 10 April 1804. Back.

[45] Schwab, Franz Berg an der Universität Würzburg, 329. Back.

[46] Collective review under Arzneygelahrtheit, Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (1802) 101 (Saturday, 3 April 1802) 31–32. Back.

[47] Anonymous review of Franz Berg’s book in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (1802) 225 (Tuesday, 10 August 1802) 327–28, here 327, following citation: 328; for a translation of the review, see the notes to Caroline’s letter to Wilhelm Schlegel in September 1802 (letter 370). Back.

[48] Schelling to Wilhelm Schlegel on 19 August 1802 (letter 369a). Back.

[49] To the Public. Rebuke of a Defamation of Honor Perpetrated in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (letter/document 371b). Back.

[50] Schelling to Wilhelm Schlegel on 3 September 1802 (letter 369d). Back.

[51] [Translator’s note: Schütz’s title translates approx. “Disposition of the facts along with official documentation proving that Herr Rath August Wilhelm Schlegel, in the rebuke in which he falsely accuses the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung of having committed a defamation of honor, has rebuked no one other than himself; with an addendum concerning the comportment of Schellingian obscurantism.”] — Schelling’s piece: “Benehmen des Obscurantismus gegen die Naturphilosophie,” Neue Zeitschrift für speculative Physik, ed. F. W. J. Schelling, 1 (1802) no. 1, 161–88; trans. as “The Comportment of Obscurantism contra the Philosophy of Nature”. Back.

[52] Schütz, Species facti nebst Actenstücken, 9. Back.

[53] Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (1799) 316 (Thursday, 3 October 1799) 25–30; 317 (Friday, 4 October 1799) 33–38. Back.

[54] Schelling, “Anhang zu dem voranstehenden Aufsatz, betreffend zwei naturphilosophische Recensionen und die Jenaische Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung vom Herausgeber,” Zeitschrift für spekulative Physik, ed. F. W. J. Schelling, 1 (1800) no. 1, 49–99, here 56. Back.

[55] Erster Entwurf eines Systems der Naturphilosophie: Zum Behuf seiner Vorlesungen (Jena, Leipzig 1799). Back.

[56] Ueber die Jenaische Allgemeine Literaturzeitung. Erläuterungen, vom Professor Schelling zu Jena. (Aus dem ersten Heft der Zeitschrift für spekulative Physik besonders abgedruckt) (Jena, Leipzig 1800). Back.

[57] Intelligenzblatt of the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (1800) 57 (Wednesday, 30 April 1800) 465–80; 62 (Saturday, 10 May 1800) 513–20. Back.

[58] See Wilhelm Schlegel’s farewell in the Intelligenzblatt of the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (1799) 145 (Wednesday, 13 November 1799) 1179 (letter/document 255a). Back.

[59] See the supplementary appendix on Friedrich Nicolai’s Vertraute Briefe von Adelheid B** and on the coquette Caroline , which includes Ludwig Ferdinand Huber’s review of Nicolai’s novel in part cited here. Back.

[61] Fichte, Gesamtausgabe, 3:4:113. Back.

[62] Die romantische Schule 730–31. Back.

[63] Schelling to Wilhelm Schlegel on 8 October 1802 (letter 371b). The two pieces were the previously discussed Lob der allerneuesten Philosophie by the Würzburg theologian Franz Berg (1802), and, in Fichte’s dispute, Schreiben eines Vaters an seinen studierenden Sohn über den Fichtischen und Forbergischen Atheismus (1798). Back.

[64] Fichte, “Über den Grund unseres Glaubens an eine göttliche Weltregierung,” Philosophisches Journal einer Gesellschaft Teutscher Gelehrten 8 (1798) (November) 1–20; Friedrich Karl Forberg, “Entwickelung des Begriffs der Religion,” Philosophisches Journal einer Gesellschaft Teutscher Gelehrten 8 (1798) (November) 21–46. Back.

[65] “Vermischte Nachrichten,” Intelligenzblatt of the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (1799) 88 (Wednesday, 17 July 1799) 700. Back.

[66] Gesamtausgabe 3:3:359. Back.

[67] Schelling to Fichte on 1 November 1799 (supplementary appendix 241.1). Back.

[68] Labienus, Höchstwichtige Beyträge zur Geschichte der neuesten Literatur in Deutschland aus den nachgelassenen Papieren des Magisters Aletheios (St. Gallen 1817), 456. Back.

[69] Ibid., 463. Back.

[70] Johannes Janssen, Zeit- und Lebensbilder, 3rd ed. (Freiburg im Breisgau 1879), 173. Back.

[71] Ibid., 177. Back.

[72] [Translator’s note: Latin (said of slander, defamation, etc.): “Something always sticks.”] Hans Jörg Sandkühler, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Sammlung Metzler (Stuttgart 1979), 69. Back.

[73] See Sandkühler, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling; Tsouyopoulos, Andreas Röschlaub und die Romantische Medizin; idem, “Der Streit zwischen Friedrich Wilhelm Josef Schelling und Andreas Röschlaub über die Grundlagen der Medizin,” Medizinhistorisches Journal 13 (1978), 229–46. Back.

[74] Helmut Prang, ed., Begriffsbestimmung der Romantik (Darmstadt 1972), 6; see also Richard Brinkmann, ed., Romantik in Deutschland. ein interdisziplinäres Symposion (Stuttgart 1978). Back.

[75] See Ludwig Hasler, ed., Schelling — Seine Bedeutung für eine Philosophie der Natur und der Geschichte. Referate und Kolloquien der Internationalen Schelling-Tagung (Zürich 1981; Stuttgart 1981); Hermann Krings, Rudolf W. Meyer, Reinhard Heckmann, ed., Natur und Subjektivität. Zur Auseinandersetzung mit der Naturphilosophie des jungen Schelling, Schelling-Tagung Zürich 1983 (Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1985). Back.

[76] See the pieces by Bernhard Krabbe, “Jahrbücher der Medizin als Wissenschaft (1805–1808). Untersuchungen zu einer medizinisch-philosophischen Zeitschrift der Romantik mit unveröffentlichten Briefen aus dem Schelling-Nachlass (Ost-Berlin),” med. diss., Münster, 1984; Guenter B. Risse, “The Brownian System of Medicine: Its Theoretical and Practical Implications,” Clio Medica 5 (1970), 45–51; Hans Joachim Schwanitz, Homöopathie und Brownianismus 1795–1845. Zwei wissenschaftstheoretische Fallstudien aus der praktischen Medizin (Stuttgart, New York 1983); Nelly Tsouyopoulos, Andreas Röschlaub und die Romantische Medizin. Die philosophischen Grundlagen der modernen Medizin (Stuttgart, New York 1982); idem, “Reformen am Bamberger Krankenhaus — Theorie und Praxis der Medizin um 1800,” Historia Hospitalium (Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Krankenhausgeschichte) 11 (1976) 103–22. Back.

[77] See Schwanitz, Homöopathie und Brownianismus 1795–1845. Back.

[78] Andreas Röschlaub to Schelling on 15 May 1802 (for entire letter, see notes to Caroline’s letter to Wilhelm Schlegel on 21 [29?] June 1802 [letter 367]). Back.

[79] Schelling, “Anhang zu dem voranstehenden Aufsatz, betreffend zwei naturphilosophische Recensionen und die Jenaische Allgemeine Literaturzeitung vom Herausgeber,” 56. Back.

[80] Frank Böckelmann, ed., Die Schriften zu J. G. Fichtes Atheismus-Streit (Munich 1969), 10. Back.

[81] Adalbert Friedrich Marcus, “An Dr. Andreas Röschlaub über den Typhus,” Ephemeriden der Heilkunde 8 (Bamberg, Würzburg 1813), 61–107, here 62. Back.

[82] Andreas Röschlaub, “Empfiehlt die Erregungstheorie zur Erhaltung der Gesundheit unbedingt den Gebrauch heftig reizender Dinge?” Hygiea. Zeitschrift für öffentliche und private Gesundheitspflege, ed. Georg Oeggl and Andreas Röschlaub, 1 (1803), 149–67, here 150. Back.

Translation © 2014 Doug Stott