Reactions to Wilhelm Schlegel’s Play Ion [*]

Contents

Background — I. (1) Karl August Böttiger’s suppressed review and (2) Goethe’s replacement review; — II. Wilhelm Schlegel’s set decorations for Ion; — III. Exchanges (part 1) concerning the play Ion between Caroline, Schelling, and Wilhelm Schlegel in the Zeitung für die elegante Welt (1802); — IV. The Berlin Performance of Ion; — V. The scandal surrounding Creusa’s Monologue in act 4, scene 1; — VI. Exchanges (part 2) concerning the play Ion between Caroline, Schelling, and Wilhelm Schlegel in the Zeitung für die elegante Welt (1802); — VII. Other Reactions to Ion

Wilhelm Schlegel began his play Ion. Ein Schauspiel (Hamburg: Friedrich Perthes, 1803) in May 1801. The first act was finished by late June, the second by the end of August, and the entirety by 19 October 1801. [1] The play premiered in Weimar on 2 January 1802 and was repeated on 4 January. It premiered in Berlin on 15 May 1802 and was then performed in Lauchstädt on 29 July and 9 August 1802, and on 6 August 1803, and in Rudolstadt on 24 August 1802. The play was not performed again in Weimar after January 1802. [2]

I.1. Karl August Böttiger’s Suppressed Review

A modest scandal surrounded the revelation of Wilhelm’s authorship of the play, who had wished to remain anonymous. [3] On 19 January 1802 (letter 341a), Wilhelm wrote to Goethe sharply alluding to Dorothea Veit’s role and suggesting that through her and through Friedrich Schlegel’s friends, his, Wilhelm’s, name had become known as the author. Goethe drafted a response at the beginning of February 1802 but never sent it: [4]

Since it is not my habit to be particularly voluble in relationships involving friendships, indeed, since I may even on occasion seem excessively dry in that regard, let me respond all the more quickly this time that I may relate my present disposition. The completion of your piece fortunately came at a time when such was a particularly welcome addition to our theater and when I myself was able to set about producing it with confidence.

I am certainly pleased that the performance was sufficiently successful to be called perfect, from which, however, one must also conclude that the piece itself was rendered as a unity the likes of which one was unlikely to incorporate into it through performance were it not already there. The premature discovery of your name did indeed immediately prompt a considerable wave of opposition that did not subside without some quarreling, the more scandalous elements of which, however, I was fortunate enough to prevent from developing any further.

The “more scandalous elements” refer primarily to a review Karl August Böttiger wrote immediately after the Weimar performance, “Über die Aufführung des Ion auf dem Hoftheater zu Weimar,” intended for the Journal des Luxus und der Moden. Goethe himself, however, got wind of it, secured copies, and suppressed it by essentially threatening the editor of the journal, Friedrich Justin Bertuch, with a visit to Duke Karl August as well as with his — Goethe’s — own resignation as theater director. [5]

Although the review itself was moderate enough, acknowledging not merely the performance, Caroline believed this rather violent muzzling sooner derived from Böttiger’s estimation of Friederike Unzelmann as a mere soubrette. [6]

The editors of Böttiger’s Kleine Schriften thought it necessary to provide an introduction to their publication of his review of Ion, pointing out the unusual circumstances of its original suppression by Goethe. Goethe relates in his diaries with respect to 1802: [7]

Now, the Schlegel brothers had profoundly insulted the opposing party, which is why a blatant attempt at opposition emerged the very evening of the performance of Ion, whose author was no secret. Between acts people were already whispering about all sorts of things worthy of reproach in the play, the occasion for which was admittedly provided not least by the rather questionable position of the mother [Creusa].

An essay attacking both the author and the theater intendant was projected for the Modejournal [Journal des Luxus und der Moden] but then seriously and energetically rejected, since it was not the regnant principle that in the same state, in the same city, any member be allowed to tear down what others had just built up.

Both the Herders and the Knebels completely rejected the play. See Caroline Herder to Karl Ludwig von Knebel: [8]

Just imagine! Böttiger writes a critique of Ion in the Modejournal in which he cannot avoid speaking the truth, and after the type had been set, Goethe demands it from Bertuch [the editor]; after receiving it, he wrote to Bertruch, telling him that if he does not immediately suppress this critique of Ion he, Goethe, will go immediately to the duke and demand his own dismissal as theater director. In the future, he also allegedly intends to supply all the theater reviews for the Modejournal himself, beginning with Ion in the very next issue.

So you can see how things stand with our “theater truth”!

And yet all this is a grand secret that is nonetheless quietly making its way from ear to ear. Böttiger rescued the typeset version as the only printed version — he will certainly send it along to you if you would like to see it.

She had already written to Knebel on 6 January 1802: [9]

The next day [2 January 1802], Ion, freely translated and adapted by Aug. Wilhelm Schlegel, was performed. A more shameless, brazen, morally ruinous piece has never been seen. Everyone in Jena was again summoned to the performance to provide applause, though by the second performance very few people attended, and by the third they no longer risked performing it, since the theater may well have been empty. Alas, my friend, how Goethe has sunk! — But enough!

In his own turn, Karl Ludwig von Knebel composed a derisive epigram “Euripides from the grave” in a letter to his sister, Henriette von Knebel: [10]

Many centuries did I here sleep, believing myself safe; Now along comes Sch[egel] to pour out disgrace on my poor head!

Although Böttiger’s review was suppressed, he had occasion a year later to publish some brief remarks in a British periodical in English about Wilhelm’s play and Friedrich Schlegel’s Alarcos, the latter of which would be performed in Weimar during the late spring of 1802): [11]

Mr. Schlegel, who, for a series of years, has been laboring in almost every department of the Belles Letters, without rising above mediocrity in any, has prepared “The Ion of Euripides” for the German Stage. He has made some alterations in the fable of the original; but these alterations are far from being improvements. Thus, e.g. instead of Minerva, he introduces Apollo himself., and makes him give to Xuthus a very lubricous description, how he had violated the chastity of his wife. Mr. Schlegel has translated some splendid passages from other ancient poets, and interwoven them with this imitation of Euripides’s Tragedy, so that his work certainly contains many beautiful gleanings; but is, upon the whole, uninteresting, and is no longer represented at any theatre, on account of the indecencies in many parts of the dialogue. The author, however, in the mean time trumpeted forth his own praise, asserting, that he had far surpassed Euripides; and unblushingly owns, that he thinks his work an excellent performance. This Mr. Schlegel possesses considerable talents for translating. He has published several volumes of a Translation of Shakespeare’s Works; in which he has indeed been guilty of the absurdity of giving, with a ridiculous Flemish precision, all the blemishes and errors of the original, not omitting even the most unimportant play upon words: he has, however, evinced, that he is well acquainted with the English, and has a great command of the German language.

A brother of the preceding has, on the contrary, brought forth a Tragedy, intitled “Alaricos,” which, for rant, absurdity, and want of taste surpasses every thing that ever emanated from the distempered brain of a writer for the Stage. The hero of this piece, a Spanish Knight, stabs his tenderly-beloved wife, because he had promised to marry a princess, whom he abhors. He does not, however, marry the princess: but stabs himself at the side of his wife’s corpse — the princess dies in a state of insanity; and the king, her father, is frightened to death by an apparition. The language of this work is in the highest degree bombastic, and so farfetched and stiff, as if it had been written for a puppet-show. The public laughed for a while at the ridiculo-horridmonster, and soon forgot it: but the brother of the author, and his partizans, do not cease assuring us, that it is a wonderful master-piece.

On 21 January 1802 Böttiger wrote to Johann Friedrich Rochlitz: [12]

Piqued by that particular nonsense [of Ion], perhaps also by prickling miasma, I wrote a critique for the Modejournal that spared the theater direction itself as much as possible [i.e., Goethe], with whom I wanted least in the world to get into a public war.

Before the piece even left the printer, however, Goethe received word of it and fulminated so violently against me and wrote such threatening billets to Bertuch that the latter immediately withdrew the pages of perdition even though he had freedom from the censor and could have proceeded quite differently indeed.

Goethe, however, immediately threatened to resign from the theater direction if such were to happen. This affair made a considerable sensation here and made anyone who is not a slave of the Schlegelian clique highly indignant. Much is probably being said about all this elsewhere as well.

I am enclosing for you, with the strictest secrecy, the retrieved proofs, but would like to receive them back because I have no other copy; I would, moreover, also request you show them to no one else and not speak about them unless others bring the matter up first. Judge for yourself whether it contains anything disrespectful of Goethe or whether, to the contrary, there is not perhaps too much praise in it.

In any case, this entire affair is making my own circumstances here even more unpleasant. So be it! I intend to be fearless and to act according to my own convictions.

Christoph Martin Wieland, in a letter to Böttiger on 15 January 1802, takes a cautious stance over against Goethe: [13]

Osmannstädt, 15 January 1802

I greatly regret, dear Böttiger, that the new year has commenced so inhospitably for you here in its very first days. Had the gods but enabled you to withstand the urge to attend Ion on 2 January as seriously as if it were the devil himself, an urge that has now had such disastrous consequences for you!

Since I knew not a word about what transpired because of this bastard of the gods, you can imagine how nonplussed I was when on 13 January I received a letter from Goethe relating to me in the most bitter wording the entire quarrel with you, the intention of which was to prevent my publishing in the Merkur what had been withdrawn from the Modejournal, or anything similar.

I had indeed heard both good and bad concerning this Ion, and could easily imagine that a judge as familiar with Euripides and with the entirety of Hellas as my friend Böttiger would have found considerable material in it for a sharp critique and, being no friend of the author and having no reason to be such, would not have been particularly compassionate with the scourge; but I could not comprehend how Goethe could feel so insulted by the article in question, all the more so insofar as it was conceivable neither that you would intentionally try to insult a man as important as Goethe in Weimar (abstracting from everything else) in a journal published in Weimar, nor that Goethe himself should feel so terribly insulted by some inadvertent bump from someone’s elbow or someone stepping on his toes.

You yourself have now resolved this previously incomprehensible riddle by sending me the corporus delicti [concrete evidence] in its entirety (which I am herewith also returning), albeit resolved truly not in a way delighting my own disposition, but, since I am your friend and as such care about what happens to you, much to my own pain. I can relate to you in a few words my own frank opinion, reflecting my innermost conviction, which you have desired to have.

As in all other things as well, I distinguish here between the formal and the material. As concerns the latter, the objections to the piece are probably accurate, though I hardly doubt that a friend of the author would not find it particularly difficult to adduce much in his defense that genuinely does have substance.

By contrast, I can neither justify nor excuse the formal elements of this article; and only presupposing that you intended to deliver irritating pricks, stings, and stigmata against Goethe (moreover, considerably more serious than the pushes of St. Radegunde and the holy father Francis of Assisi), can I comprehend why, after reading over what you had written (perhaps even that very night, still flushed by the ire that heated you during the performance), you yourself should immediately have realized that Goethe neither would nor could ever, in his entire life, be able to forgive you such public flagellation of Ion, the author, and the person responsible for the performance who spared no effort in making that performance successful.

And yet, since it is equally inconceivable that (unless it be the day before you were to leave Weimar forever) you might actually have wanted, intentionally and brazenly, to make a man like Goethe into your irreconcilable enemy, there can be no other explanation that might render the matter even partially comprehensible than the Shandyan hypothesis regarding the devils of the Archbishop de la Casa, which, insofar as you yourself unfortunately worked on your article en pathesi, must have been assembling in legion numbers around your very inkwell. [14]

An adequate explanation of this, my frank but honest appraisal, would require more time than I have at present, nor do you likely even need such, since your own excellent intellect, were you to reread your piece in a leisurely moment, would unerringly deliver its own sting at every word blackened by your kako daimon [bad demon], sarcasm, ironic praise, kiss of Judas, and stab in the back.

Hence let me add merely this: were you my own biological brother or son, I could, quoad hunc passum [who to this extent suffered], neither defend nor excuse you; and in Goethe’s place I would have perceived the matter the very same, at the very same level, and would have reacted the very same way he in fact did.

The worst part of this whole affair, the thing that makes me most sorry, is that nothing can be done now. Goethe views it as a guerre ouverte [open war], moreover, as a war of annihilation, in which only one of the two parties can remain, or rather: in which one must vacate the field.

Wieland wrote an even more discouraging letter to Böttiger on 19 January 1802: [15]

Well, now Monsieur Schlegel is enjoying his triumph, and you cut a sad figure next to that gentleman. The worst part is that nothing can help you now, since Goethe will not view your silence as at all creditable, and it is as impossible for you to reconcile with him now as it would be to pull the moon down from the sky with your teeth.

I have also been assured that whatever might appear in any German daily that is critical of Ion will be attributed to you. An honorable guerre ouverte would be the best thing for your own renown, but who could possibly advise you such in your present situation? — I for my part intend to keep silent concerning this entire mess, though I will be translating Euripides’s Ion for the Attisches Museum, indeed, this very year.

I.2. Goethe’s Review of Ion in Journal des Luxus und der Moden

Goethe’s threatened replacement review appeared as part of his article “Weimarisches Hoftheater,” Journal des Luxus und der Moden 14 (1802) (March) 136–48, here 140–43:

In this situation, the theater management could not but ardently welcome a play such as Ion. Whereas The Brothers [Friedrich Hildebrand von Einsiedel, Die Brüder. Ein Lustspiel nach Terenz in fünf Akten (Leipzig 1802) was performed in Weimar on 21 December 1801] had approached the disposition of Roman comedy, here the goal was an approximation of Greek tragedy. Purely from a physical perspective, the prospect of an extremely effective performance was promising, since the six characters at once represented an enormous variety.

A lad in the blossom of youth, a god as a youth, a stately king, a dignified elderly man, a queen in her best years, and a sacred, elderly priestess. Care had similarly been taken to ensure distinguished, alternating costumes, and the stage set itself, which remained the same throughout, purposively arranged. [The characters are from left to right: Pythia, Xuthus, Ion, Creusa, Phorbas (Apollo not included):]

The figures of the two elderly men had been tragically enhanced by the use of deft masks, and since the figures appear in various configurations over the course of the play, the succession of groupings was quite pleasing to the eye, and the actors performed this difficult task with all the more facility by having become accustomed, through their earlier performances of French tragedies, to steady gestures and disposition and appropriate positioning on stage.

The play’s primary situations provided the occasion for more animated tableaux, and one might flatter oneself with having provided a largely consummate portrayal in this regard.

As far as the piece itself is concerned, one can say quite without prejudice that it presents itself quite well, progresses in an animated fashion, that extremely interesting situations arise for tying the dramatic knot that is ultimately resolved in part through reason and persuasion, and in part through a miraculous epiphany.

Otherwise the piece is utterly transparent for those not unfamiliar with mythology, and performs the pedagogical service of prompting the other, less educated spectator to seek out a lexicon of mythology at home in order to learn something about Erichthonius and Erechtheus.

No greater respect can be shown the public than not to treat it like rabble. The rabble pushes and shoves its way quite unprepared to the theater, demands that which can be enjoyed immediately and directly, wants to look, be astonished, laugh, cry, and thus presses the director — who depends on them — more or less to condescend to their level, thereby overstretching the theater, on the one hand, and dissolving it, on the other.

We are quite fortunate to be in a position to assume that our audience, especially, as is reasonable, if we reckon those from Jena, will be bringing with them something more than merely the money for their tickets, and that those who experience an obscure or even unenjoyable element at the first, careful performance of distinguished pieces, are nonetheless inclined to allow themselves, with regard to the second, to be better instructed and initiated into the broader goal.

It is solely because our situation allows us to offer performances that appeal to the taste of a more select audience that we are in a position to seek out all the more energetically such that will appeal to a broader one.

Should Ion be performed in other theaters as well, or be published, we would wish to see a competent critic not merely juxtapose this new playwright with the earlier one from antiquity with whom he is already long familiar, but also take the opportunity once again to compare antiquity with modernity in the larger sense. Such would bring to expression many points that, although already addressed on several earlier occasions, can never be addressed too often.

The new author, like the old, has certain advantages and disadvantages, but with quite reverse positioning. What was favorable to the one, burdens the other, and what is favorable to the latter, runs counter to the former. The present Ion cannot be appropriately compared with the Ion of Euripides unless these broader observations precede such a comparison, and we will owe considerable gratitude to the art critic who clarifies for us, using precisely his present example, the extent to which we can and should be followers of the ancients.

II. Wilhelm Schlegel’s Set Decorations for Ion

Erich Schmidt remarks that, despite Wilhelm Schlegel’s self-righteous asseverations to the contrary, this “bloodless, feeble piece” owes to Euripides alone whatever interest it managed to elicit. [16] Goethe read it on 20 October 1801, calling it, as cited above, a “most welcome” addition to the court theater in Weimar, then expended considerable effort and care in its performance, for which Wilhelm himself supplied painstakingly precise “Annotations concerning the Set of Ion and its Implementation”: [17]

Annotations concerning the Set of Ion and its Implementation

The primary set is the temple of Apollo at Delphi. A peripteral Doric temple, six columns; the entire arrangement of Parian marble. This temple is to be situated in a peribolus, or temple precinct, in front of which there is to be a symmetrically planted grove in which a laurel tree stands on the spectator’s right, a sacrificial altar on the left.

The remaining trees of the grove are to be painted on the side wings. They are to be poplars, as an allusion to Phaethon’s death, whose sisters were turned into such trees on that occasion; except on the left, directly behind the altar, where two cypresses are to be placed to set off the positioning of the altar. The laurel tree, however, which through its trunk must exhibit the slight evocation of a feminine form, with two main branches instead of arms, and a third that has been broken off as the head: this tree must preferably not be painted on a wing flat, but rather made with a completely round trunk with real branches, since it is to shake and its leaves rustle at Apollo’s appearance, whereas a painted wing flat can shake only left and right, producing an inferior effect (act 5, scene 3; Apollo appears in scene 4).

The altar, too, since Creusa is to flee onto it (act 4, scene 1), must be present as a completely concrete prop. The plinth must measure 12 square feet and be two feet high. Ancient temple construction requires high steps, and the style of the tragic performance will also profit from such if one makes all the steps that actors must climb as steep as possible, thereby forcing their gait to correspond best to the element of heroic dignity. The altar’s plinth is accordingly to have 3 steps in the front, each 8 inches high and no wider. The altar itself is to be positioned in the middle of the plinth and measure 6 square feet and a bit over 4 feet high, perhaps 4 1/3. Let it be painted to appear as if made from rosso antico [red stoneware] marble, and its plinth as if from granite.

The foreground wall of the peribolus is free-standing such that one can walk between it and the rear set scenery. It opens up in front to the breadth of the proscenium, or 40 feet. In this opening, 7 or 8 steps lead up into the peribolus, each step 7 inches high and 10 wide. Their more modest height derives from the necessary perspectival narrowing, the broader width from the need to assist the actors, who must often ascend the steps, though also to make this particular rise more imposing without, however, making it excessively high. The foreground wall should fully enclose these steps, and must thus genuinely turn around the corners at both sides.

Behind these steps, at an appropriate depth — a depth which, to the extent the theater dimensions allow, must not be too narrow — the frontispiece rises with its six columns, similarly free-standing before the rear set scenery. This is a cut-out decoration, and since accordingly the columns do not possess any real curvature, the distance between them and the back surface hardly need equal the measurement of the breadth of the corner columns, approximately 4 or 4 1/4 feet. This façade is to be as large as possible, and so that the painter may maintain as closely as possible its character, a geometric outline and ground plan is supplied indicating dimensions. [This addendum is not extant.] These dimensions are figured such that the radius or the breadth of the triglyph is 15 inches. A is the outline and B the ground plan. Everything in the latter positioned behind the line a–b from the temple structure is to be painted on the rear set scenery, the front columns, however, with the gable, on the cut-out set piece standing in front. The three temple steps, however, must again absolutely be concretely rendered as far back as the rear set scenery. Together they are one radius high and each 8 inches wide. If (for example, to avoid offensive, harsh shadows from the frontispiece on the rear set scenery) it becomes necessary to position lamps behind, one would have to spread a covering piece between them, at the height where the real ceiling of the forecourt would have to be so that the actors, when entering the column arcade, do not betray the artificial elements of the set through their unnatural illumination. Such is indicated in the cross section c by the transverse line d.

The temple door, cut out within the rear set scenery, has a purple curtain hanging before it that always hangs down such that the actual door opening is completely covered, and the actors pull it aside when exiting; when Apollo finally appears in the door of his temple (act 5, scene 4), however, the curtain in the middle is raised as indicated in the drawing. To enhance this appearance, a final, stepped elevation must be erected behind the curtain at a height of the door’s threshold, on which Apollo appears as if standing on the floor of the temple cell, as can be seen at e in the aforementioned cross section c.

Finally, on the rear set scenery, at both sides of the temple, one sees the interior column arcades of the spacious peribolus with doors leading to the priestly quarters. Hence here the columns are rendered such that their diameter is a fourth smaller than that of the temple columns, and their entablature has no frieze.

The temple’s column arrangement and hence also the smooth door posts are of Parian marble, the walls, however, as well as the entire peribolus, of travertine stone. By contrast, the plinth of the front wall of the temple courtyard is to be of granite, and the steps of Trieste stone, which is not as yellowish as travertine.

The temple gable area on the cut-out set is to be filled out and decorated with bas-reliefs depicting Apollo among the muses. Since there was not enough space on the drawing of the overall set to depict this appropriately, the fronton there has been left blank, and the enlarged sketch for the bas-relief appended on a special page. [This addendum is not extant.]

The only possible alteration with respect to the given dimensions would be that the quadriga on the peak of the temple be painted gilded rather than bronze, which in part accords to the fashion of antiquity and in part fits various sections of the play better, a notion that occurred to the draftsman only after the renderings were finished.

On the back set scenery, farther to the spectators’ right and beyond the peribolus, one sees the town spread out at varying height; but on the left a pine as an indicator of the climate, and then a peak of the Parnassus (act 1, scene 1), which is treeless on top and surrounded by a forest at the base.

The air is to be quite serene, and no clouds are to be added. The scene is to exhibit the illumination characteristic of early morning (act 1, scene 1), since the sun does not yet stand high in the sky, and its light falls from a forward position on the right.

The front grove need not be particularly deep; it need take up only three wing flats. All the more, however, should one be careful not to be too frugal with the depth of the peribolus, from the front steps up to the steps of the temple; 10 feet is here the minimum. Since the stage perspective narrows toward the back, whereas the actors cannot be reduced commensurate with that narrowing, one must assist the deception by positioning as many lamps behind the front wall of the peribolus to prevent the actor’s form from being accompanied by excessively harsh shadows when entering the same. This will also cause the horizon on the back set to appear brighter and thus clearer, and it will even be advantageous if it appears as if a higher, unusual light reigns around the temple of the sun god himself. But such must not in any way be overly obvious.

A water vessel in the form of a basin of white or yellow marble must stand between the front wall of the peribolus and the steps of the temple. It should be as large as space allows, but not so large that it blocks the passageway there. It may thus be oval and have the following profile [drawing of vessel: a basin widening toward the top with recessed sides and two hanging handles; act 1, scene 1]. It is not, however, to be more than a foot-and-a-half tall. In the perspectival outline, its position is indicated by a. On the uppermost step of the temple itself, in the second column expanse on the left, as indicated in the geometrical outline at f, a basket is to be positioned whose form the costume designer is to determine and in which the garlands have been placed (act 1, scene 1). The geometrical sketch also indicates how the latter are to appear when fixed to the columns. To this end, cords are to hang far enough down on the rear sides of the columns that Ion can comfortably attach his garlands to them without the spectators sensing that he has to expend excessive effort, and then they must rise up on their own. The garland intended as adornment for the upper part of the door should already be equipped with two bronze buttons affixed, for the purpose of hanging the wreath, to either corner in the fashion of antiquity, as shown in the geometric sketch.

When the curtain rises, the stage is empty to enable the spectators to accustom their eyes to the locale. Then Ion emerges from the peribolus to the right. His bow and quiver are leaning next to the door of the temple to the right. (Act 1, scene 1.) Once he has picked them up, he enters through the middle column space, taking up for a moment the same position in which Apollo appears at the end. He then strides forward and down into the grove. Before he gets before the altar line, Pythia must already have appeared to him (act 1, scene 2), coming from the same locale, whereupon she then comes down to him in the grove. At their first entry (act 1, scene 3; act 1, scene 5; act 1, scene 7), Phorbas, Creusa, and Xuthus all emerge from the first wing expanse to the right, immediately behind the laurel; and when Pythia enters the temple for the first time, Phorbas exits where she has just left (act 1, scene 3). When Ion, leaning against the laurel tree, sings his hymn (act 2, scene 1), Xuthus comes out of the temple door and immediately hastens down into the grove (act 2, scene 2). When Xuthus and Ion go to prepare the banquet meal, they exit to the right through the rear wings of the grove (act 2, scene 3). Exactly there is also where Creusa emerges when she flees, disappearing then behind the altar; the same for Ion (act 3, scene 1; act 3, scene 2).

But when Creusa returns, she enters from the left, in front of the same, from the foremost wing expanse, fleeing then onto the altar, sitting down on the altar steps, to the left in the place indicated in the perspectival sketch by b (act 4, scene 1). By contrast, Ion returns from behind the altar from the same place where he previously exited, strides across the middle of the stage, and, when approaching the laurel tree but before coming out in front of it, sees Creusa (act 4, scene 3). Hence he is positioned wholly to the right — behind the laurel tree, toward the rear expanse between the line of the tree itself and that of the altar — at the moment he intends to shoot her. This position is indicated by c in the perspectival sketch.

In act 3, Pythia, as always, enters from the peribolus, and at Creusa’s return she has withdrawn into the temple colonnade, where she actually should lie down on the floor in front of the door (act 3, scene 3; act 3, scene 4). So also Creusa, when, veiled, she intends to surrender herself to the arrows, should lie down on the altar steps (act 4, scene 3). Pythia exits right into the peribolus, then returns thence with her maidservant (act 4, scene 4) and addresses Ion just as the first time while still descending the steps of the peribolus. When Xuthus brings captive Phorbas, he necessarily enters from the stage right, approximately from the middle wing expanse (act 3, scene 4), and Pythia in the meantime is standing stage center, to the rear, in the grove . In the final scene, all characters are stage front in the grove such that Ion, when he invokes the god, again initially stands at the laurel tree (act 5, scene 3). This tree must be positioned forward as far as possible, and this time Ion must not touch it. At the first signs of the imminent manifestation, the characters move a bit toward the background, as if miraculously drawn there.

A soft cloud falls vertically to the front of the temple door with a soft clap of thunder and then immediately disappears (act 5, scene 3). This must take place as swiftly as possible, and while the cloud conceals the door itself from the spectators, the curtain there must be raised and the god be seen standing on the threshold in glorious radiance (act 5, scene 4). The curtain, however, must be raised high enough for the god and his radiance to have ample space, so that the grandeur of the empty space not diminish his stature, which, that it may attain its proper height at least to a certain extent, should have extremely thick buskins on his feet.

It should also be noted that the basket containing the flowers must not remain beneath the columns; it is thus advisable for Pythia’s maidservant, as a silent character, to emerge from the left out of the peribolus and take it away while the priestess enters the temple and Ion greets the queen (act 1, scenes 3–5).

Bernhard Seuffert, who published this piece, felt fairly certain Wilhelm prepared it for the performance in Weimar and that Goethe used it in his production (though it may not have been used for the later Berlin performance). Caroline’s own account as well as that of Karl August Böttiger [18] confirm as much. Friedrich Tieck supplied the drawings of the various characters as an accompanying colorized copper engraving in the Journal des Luxus und der Moden. [19] The characters are from left to right: Pythia, Xuthus, Ion, Creusa, Phorbas (Apollo not included):

Friedrich Tieck apparently did not, however, do the set design, since Caroline found it necessary to supply her own drawing of the temple while referring Sophie Bernhardi to her brother’s sketches for the costumes. [20] Wilhelm’s detailed remarks apparently did not suffice for the painters in Weimar, who chose a temple on an old gem as their model. Neither Goethe nor Caroline, however, was satisfied. [21] Goethe wrote to Wilhelm on 3 May 1802: [22]

If you can secure for me a light sketch of Genelli’s set, I would, insofar as possible, implement his idea in our own theater. The temple was the weakest part of our performance, and is something I would very much like to replace with something more appropriate in the future.

Goethe is referring to the plans Hans Christian Genelli had drawn up for the Berlin performance, though even Genelli himself criticized the actual implementation of his plans in Berlin. It is unclear whether Genelli’s designs were used for the performance of Ion in Lauchstädt (29 July, 9 August 1802; 6 August 1803) and Rudolstadt (24 August 1802, 1803). [23]

III. Exchanges (part 1) concerning the play Ion between

Caroline, Schelling, and Wilhelm Schlegel

in the Zeitung für die elegante Welt (1802)

In his appendix to the 1913 edition of Caroline’s letters, Erich Schmidt reproduces Caroline’s review of the Weimar premiere of the play, [24] written with Schelling’s help and, so Schmidt, apparently without any real conviction or enthusiasm on her own part, but rather with considerable effort and quite clumsily insofar as it merely presupposes the content of the play.

Goethe, however, praises her review in his article “Weimarisches Hoftheater,” [25] in which he also discusses the performance of Ion at some length:

We hope that this particular friend of our theater who . . . reviewed the performance of Ion with equal portions of insight and fairness in the Zeitung für die elegante Welt, issue 7, might also take on the task of doing the same with regard to Turandot. [26]

Although Caroline did indeed consider doing such a review, she never carried out the plan. [27]

In any event, the (so Erich Schmidt) [28] vain author himself, however, namely, Wilhelm, was quite dissatisfied with Caroline’s review, and a perusal of the attendant public documents evokes an increasingly comical sequence of in part anonymous epistolary responses in the Zeitung für die elegante Welt (as letters to the editor) extending from January through August 1802.

The first installment in this exchange was Caroline’s initial review after the Weimar performance on 2 January 1802.

(1) “Ion, a Play after Euripides Performed at the Court Theater in Weimar,”

Zeitung für die elegante Welt (1802) 7 (Saturday, 16 January 1802), 49–54

|585| On January 2, Ion, a play in 5 acts, was performed for the first time at the Court Theater in Weimar. Apart from the fable, which indisputably derives from the play of the same name by Euripides, the author is responsible for virtually the entire adaptation, of which there have previously been five or six different others with widely varying characteristics. It seems advisable for now not to say anything about this insofar as it would then be more difficult adequately to survey the play itself and its performance in a single evening. The overall impression, however, was one of complete harmony.

The setting is the area before the temple of Apollo in Delphi. The temple itself was in the background, while an altar stood in the foreground on one side, the sacred laurel alluding to the transformed Daphne herself on the other.

Mademoiselle Jagemann performed the role of Ion, more a boy than a youth, a consecrated servant of the god, a true divine boy in the serene priestly costume. [29]

[Here Karoline Jagemann in the role of Ion, 1803, by Jakob Wilhelm Christian Roux:]

She wore a white, doubly wrapped chiton folded quite precisely in front and extending down to her knees, though leaving the latter uncovered, with a cloak of bright purple fastened at the breast and extending in the back |586| below the knees in unequal lengths, her hair arranged in curls with the Apollonian ribbon over her forehead and a laurel wreath. Most of the time she also had a quiver on her back fastened over the cloak, and carried a golden bow.

And indeed, the audience’s interest in the piece was aroused immediately after the first scene precisely by her initial appearance and by the extremely skillful characterization she brought to the role. She performed her temple service during the earliest part of the morning, setting wreaths on the walls and aspersing the steps. When she then fetched her light weapon, which was hanging on the laurel tree, that she might hasten into the nearby forest, her tone took on such a beautiful lilt that one thought one was actually hearing the sound of her golden bow. Such at least seemed the effect she had on the audience, since the initial greeting of Pythia almost got lost amid the applause.

The dramatis personae included Ion; then also Pythia; Creusa, Queen of Athens; her spouse, Xuthus; along with Phorbas, the old servant of the house of Erechtheus. The weight of the various roles was almost equally distributed, all the roles being equally necessary and hence satisfying within the play itself. It was in this spirit as well that they were performed. The overall coherence was complete, and the performance must have been directed with extreme care, for the entire charitable nature of the monarchy emerges in the actors’ state. Even far larger and more eminent theaters in Germany will have a difficult time equaling what has already been accomplished in this theater at various times. It seemed almost incomprehensible how properly even the most difficult passages were delivered. Although the play is in iambs, it did also contain various other, more difficult metrical forms, including a hymn for Ion |587| that Mlle. Jagemann, perhaps because of the lack of music, which would have bestowed considerable charm on this particular moment, was required to speak, and a monologue for Creusa consisting largely of anapests. [29a] In neither presentation, however, could one detect false accentuation. An element of musical precision emerged here of which one can have no concept amid the naturalism and republicanism of other theaters. [30] That which in such a context can so easily turn into mannerism — and occasionally does indeed turn into such — was rendered here so skillfully as to appear utterly free of mannerism, thereby attaining a new level of excellence.

With the aforementioned monologue, one that is important for the cohesiveness of the play and which keeps the audience in perpetual suspense such that it virtually constitutes a monodrama in and of itself, Madam Vohss delivered a performance surpassing everything she has hitherto accomplished. Her most successful moment otherwise was without a doubt when she kneels in reconciliation and with dignity before her spouse, and simultaneously moderates all the bitterness that might otherwise attach too easily to this particular role; one might perhaps reproach her only for having an appearance that was too charming for such a sublime ruler. As for her costume, she wore a white chiton girded once and with short, broad sleeves that just covered her shoulders, and a blue cloak copiously draped over one arm that also occupied the other, both with radiant embroidery; and a diadem on her head [portrait of the actress Friederike Vohss from by Westermayr, frontispiece to the Theater Kalender auf das Jahr 1799 (Gotha 1799)].

Madam Teller has never appeared more to her advantage than here, cloaked in multiple, fine white garments with silver embroidery and the veil of Pythia extending down to her forehead. During Creusa’s monologue, she projected an utterly magical appearance in the door of the temple |588| when a bright radiance illuminated her from the interior. She spoke her beautiful, all-smoothing role perfectly.

The king, to whom the author accorded every possible element of royalty as well as a certain magnificence of bearing, was played by Herr Vohss in an extremely noble style and with a consistent sense of propriety, and one might even maintain that it was precisely through this character that the harmony of the performance itself was rounded off and perfected. Moreover, he looked quite excellent, dressed in a yellowish chiton extending to the knees and a red cloak worn according to the genuine model of antiquity with golden trim and with his black, curly hair and beard lending masculine emphasis to his entire bearing.

He readily elicited and skillfully maintained the audience’s rapt attention for what was in part a necessary and in part a decorative narrative in the third act that constituted as it were a broad, peaceful stretch after two rather passionate appearances of Creusa and Ion.

The role of Phorbas seemed personally written for Herr Graff and for the unique characteristics this highly respectable artist brings to the stage. During one scene, in which the splendor of the house he has served his entire life seemed in jeopardy, he stood there with unmistakable import, wrapped in his broad white cloak of white wool, then breaking forth suddenly with all his repressed wrath, consistently vehement just as such a powerful old man would have been, rather than plying the queen pitifully. Every line he had to speak was in the best of hands.

(Portrait of Johann Jacob Graff by J. Schmeller; Goethe Nationalmuseum in Weimar.)

The character of Ion, however, was greeted with special fondness at every appearance, when the initial, pleasing impression was repeated.

The pure sound of her voice, which with this artist is never |589| wont to fall into feminine softness, and a certain virginal brittleness, boldness, and circumspection of disposition bestowed upon this delicate, pious role a uniqueness that cannot be extolled too highly. She maintained this high level even amid several minor mistakes. Welcoming the arriving queen with considerable grace, she then speaks the following words with a genuine element of shyness:

“Utter no blasphemy, unknown queen!”

And as brittle as she countered the tenderness of the alleged father, just as movingly did she afterward take hold of the mother’s head with both hands when kissing her as such. And just as graceful were the gestures with which she inspected the small basket on her knees that once served as her own cradle, and with which she lifted up the two golden serpents entwined around both hands that announce to her the sublime race, simultaneously providing the audience with a clear view. With her striking profile, beautifully curved lips, blue eyes and blond hair, in the final analysis she almost wholly reflected the appearance of a young Apollo; and it was quite appropriate for her trustingly to ask the god for the sign, and then in a free and childlike fashion to lift her own countenance toward his appearance while the others bow their heads.

In such a superior production, it cannot be viewed as simply chance that at the beginning of the play she remains standing for several minutes in the entry to the temple with her bow in hand just as does Apollo in the exact same costume at the end. In any event, the latter positioning did indeed quite successfully evoke the former for the mind’s eye.

This particular appearance of Apollo provided an extraordinarily resolute and successful conclusion to the play’s animated and complicated plot. This appearance came about in an extremely simple fashion |590| by being first announced by a clap of thunder, after which a cloud descended before the open gate of the temple from which, just as it was descending, Apollo himself emerged while, behind him in the interior of the temple, a transparent sun became visible whose rays seemed to emanate from him. [31]

The figure of Apollo came across very well, and Herr Haide performed equally well in speaking the god’s lines composed in festive trimeters, lines which — considering that the magnificence of a god is indeed infinite — might have been spoken perhaps even more resonantly. Nothing, however, could diminish the overall stirrings of contentment and satisfaction with which the solemnly serene resolution of the play was greeted.

(2) The exchange of responses now begins, with the Zeitung für die elegante Welt (1802) 25 (Saturday, 27 February 1802), 199, publishing a brief “Correction concerning the Play Ion” signed by “Sg.” [translation not included here]. [32] The reviewer acknowledges the originality of the piece over against a simple-minded correspondent in the Oberdeutsche allgemeine Litteraturzeitung [33] and a correspondent from Gotha who spoke only about the “German adaptation” of Euripides and about the choruses.

(3) Yet another essay followed this one, “Jon, neues Original-Schauspiel,” Zeitung für die elegante Welt (1802) 41 (Tuesday, 6 April 1802,), 321–25, almost as long as Caroline’s first one and again anonymous, [34] but now con amore. Here the section in which the anonymous letter writer, presumably Wilhelm himself, provides a brief description of the story line (ibid., 323–24):

The action commences in the early morning, with Ion performing his temple service and then picking up his bow and arrows, quite in the image of Apollo. Pythia approaches him, and from her lines we learn various things about Ion’s circumstances and situation. These two scenes yet breathe the pure, rarified air of the temple. In the third scene, an unknown old man enters as an emissary, and with him, the external world intrudes, as it were, into the sanctuary, bringing with it disquiet and confusion. This scene is purely introductory.

Ion’s ensuing, brief monologue provides the transition to scene 5, in which Creusa appears. The old man has already acquainted us with her public wish; she places her profound secret, though without mentioning her name, into the breast of innocence, namely, that she bore Apollo’s son.

This and the following scene exhibit an elegiac character (scenes in which Creusa, alone, confesses to have been that friend about which she spoke to Ion, and in which the audience becomes almost certain that Ion is indeed her son, though things are arranged such that the characters themselves do not come upon this same idea); the appearance of Xuthus, returning from the cave of Trophonius, whose dark, nocturnal prophecies are nicely contrasted with the serene prophecies of the Delphic god, inserts an anxious, ominous element into the action.

Ion appears first in act 2, and, like his model Apollo, plays the lyre. Xuthus comes out of the temple seeking the fulfillment of the oracle that has promised the next person he meets to be his son. He meets Ion, and a gentle, elegiac scene depicts the youth’s vacillation between sanctity and the restive activity of the hero and ruler. Creusa joins them, begrudging and spurning Ion’s solicitations.

After Ion and Xuthus have exited the scene in order to prepare a banquet, Phorbas (the emissary mentioned earlier), driven by affection for Creusa’s family, advises her to poison Ion. The crime has now wholly penetrated into the sacred circle. This wicked attempt is then made between the second and third acts but thwarted before it can be executed. Creusa flees across stage with Ion unknowingly pursuing his own mother with bow and arrow, in this wrathful form now appearing for the third time as the image of Apollo.

Pythia relates to Xuthus what has happened, enflamed with a desire for revenge against the fettered Phorbas and his absent spouse, a desire Pythia’s gentle wisdom is unable to extinguish completely. This agitation and perturbation is gradually calmed in act 4.

Creusa returns exhausted from her flight and seeks refuge at the altar. Pythia, eavesdropping on her monologue, learns that Ion is her son and leaves to fetch proof of his birth. Ion similarly returns from his fruitless pursuit, sees Creusa, whom even the altar itself can hardly protect from his noble wrath, and is about to shoot her with an arrow when Pythia returns, prompting a touching scene of recognition between mother and son.

In act 5, a reconciliation takes place between Creusa and Xuthus, and finally, to everyone’s satisfaction, Apollo himself appears, that he may acknowledge Ion as his son. The play thus concludes by reestablishing the same sacred peace and calm that dominated in Delphi at the beginning.

Here, then, one has complete harmony, complete satisfaction. The dispersed poetic sections in Euripides have been organized in part through invention, and in part through recasting of older material, into the totality of a true work of art.

___________________________

Because all the exchanges except Wilhelm’s final response (see below) were anonymous, and because Horst Fuhrmans disagreed with Erich Schmidt’s attribution of authorship in the 1913 edition of Caroline’s letters, a digression at this point concerning that authorship will be helpful in following the sequence of authors and responses.

Horst Fuhrmans, in his discussion of the authorship the two articles just mentioned, [35] Zeitung für die elegante Welt (1802) 25 (27 February 1802) and 41 (6 April 1802), cites Schelling’s letter from Jena to Wilhelm in Berlin on 16 July 1802: [36]

Quite by accident, and long after I had forgotten it even existed, I came across the letter in the Elegante Zeitung regarding the account of the Weimar performance of Ion, and I confess I could not help being a little perplexed, [37] and, so that this fun might be continued a bit further, genuinely did prepare something concerning it that Spazier has promised to include, even though the review comprising four printer’s sheets on the Berlin performance has pressed him a bit in view of the entire dispute concerning Ion. [38]

In consideration of the discourtesy in which the author [i.e., Wilhelm himself, though Schelling is here allowing the “game” of anonymity to continue] allows himself to engage toward a lady [i.e., Caroline], and the delicacy of feeling of which one can believe him capable, I felt I had to go at him a bit harshly at every turn; in the meantime, however, I do hope he will understand how to make sense of it by way of his otherwise fine sensibility.

That is, Schelling here announces to Wilhelm that he, Schelling, will come to Caroline’s defense in a coming letter to the editor, though all the while maintaining the cloak of public anonymity. His contributions were published in the Zeitung für die elegante Welt issues 90 and 91 (29, 31 July 1802) (translation not included here).

Horst Fuhrmans provides the following summary and explanatory note: [39]

The performance of A. W. Schlegel’s Ion on 2 January 1802 in Weimar had stirred up considerable dust. Caroline herself had sent a review of the performance to the Zeitung für die elegante Welt 7 (16 January 1802). Karl August Böttiger had intended to violently “shred it [the play] to pieces.” Only the extremely energetic intervention of Goethe himself prevented this “shredding critique” from being published. . . . Since the piece had been viewed as unoriginal, that is, as merely a kind of translation of Ion by Euripides, issue 25 (27 February 1802) published a “correction” signed by “Sg.” It was probably written by August Wilhelm Schlegel.

Schlegel was not particularly pleased with Caroline’s review, alleging that it addressed only the actual performance while saying nothing about the piece itself. Hence he resolved to publish something “against” Caroline’s review. [40] A second article appeared in issue 41 (6 April 1802). In his own edition of Caroline’s letters [i.e., the present edition], Erich Schmidt suspected or assumed that the article had been written by Caroline and Schelling and thus published it in his edition. [41] It was certainly not by either Caroline or Schelling. As already said, it was in all likelihood by A. W. Schlegel himself, or by a friend whom Schlegel prompted to write it. Schelling thought that Caroline had not come off well at all in this particular article, and he accordingly responded in issues 90 and 91 (29, 31 July 1802).

In his article there, he suggested that the author [i.e., Wilhelm] of the submission in issue 41 (6 April 1802) had understood little of the whole, and that one could only pray: God save us from our friends. Schelling’s formulations above [42] show that he knew A. W. Schlegel was the author (in reference to the notice in issue 41). Cordially criticizing the article in issue 7 (the one by Caroline on 16 January 1802) had constituted a bit of “fun” for Schlegel, and now Schelling in his own turn created some “fun” for himself, namely, to “dispense” with the allegedly unknown author in issue 41.

Karl Spazier, editor of the Zeitung für die elegante Welt, had in any case concluded those articles [i.e., Schelling’s] in issues 90 and 91 (29, 31 July 1802) with a note to the effect that, really, enough, indeed almost too much, had already been said about Ion (in issues. 81, 82, 83, Hans Christian Genelli had discussed the Berlin performances on 15, 16 May 1802 in depth), and the best course would now be to let A. W. Schlegel himself the last word. And so it was. Schlegel published an article in issues 100 and 101 (21, 24 August 1802), acting as if all the previous authors were unknown to him.

The following attribution seems to reflect the correct authorship:

(1) Caroline: Zeitung für die elegante Welt 7 (16 January 1802)

(2) Wilhelm: Zeitung für die elegante Welt 25 (27 February 1802)

(3) Wilhelm: Zeitung für die elegante Welt 41 (6 April 1802)

(4) Schelling: Zeitung für die elegante Welt 90, 91 (29, 31 July 1802)

(5) Wilhelm: Zeitung für die elegante Welt 100, 101 (21, 24 August 1802)

Hans Christian Genelli discussed the Berlin performance of Ion (15 May 1802) in the Zeitung für die elegante Welt 81, 82, 83 (8, 10, 13 July 1802)

___________________________

(3)

“Ion: A New, Original Play (To the Editors),”

Zeitung für die elegante Welt (1802) 41 (Tuesday, 6 April 1802,), 321–25

|590| In issue 7 of your newspaper, you included a report on the performance of an extremely interesting play in Weimar, Ion, which I read with great pleasure. Your correspondent seems to be a man who has made a thorough study of what constitutes dramatic or pictorial effect in the theater and who knows how to express his insights quite well. Perhaps he has merely focused his attention too exclusively on the theatrical effect and has become accustomed to examining dramatic works from this perspective alone. How else might it be possible to dispense with this play, which in and of itself does otherwise invite such a plethora of interesting observations, with so few and — why should I not be quite frank? — such inadequate and incorrect remarks? – Please permit me to justify this assessment with a few remarks of my own.

|591| The reviewer maintains that the author of Ion worked after the model of Euripides. But is he really familiar with this Euripides? Is he aware of how fleetingly this rhetorical writer, with whom the ruin of Greek drama itself commences, comprehends and treats his subjects? How he continually strives for the most material of effects and to that end alters the myths? Has he examined how everything in Euripides is calculated for the momentary effect, for that which is both quick and shocking? How all his plays are geared solely for visual effect, indeed, for a one-time performance in whose haste the harmony and cohesiveness of the whole cannot be precisely comprehended? And how after repeated readings through which this tension is diminished, they thus lose their effect? Furthermore, if we might speak of Euripides’ Ion in particular: How disharmoniously do all the various parts of this composition fall asunder and flee one another! What repetitions in the descriptions, in the story itself! How often is the abandoned condition of Creusa described! How strange that Xuthus comes together with his spouse but a single time, and even then only in an extremely uninteresting moment! And can one possibly say about the fact that, at the end, the chorus, Creusa, Ion, Pythia, and Minerva all come to an understanding almost like conspirators in resolving to deceive Xuthus about Ion’s true lineage? And what a repugnant role does the latter play toward his own mother, whom he interrogates almost as if in court concerning the signs surrounding his birth! And the way the lengthy, wholly extraneous discourses disturb any sense of cohesiveness and symmetry!

Let us now consider the German Ion in comparison. Nothing in it belongs to Euripides except what in reality does not belong to the latter either, namely, the fable, which nowhere appears as complete as it does here, which is why anyone who works with this subject matter will of necessity have to take refuge in Euripides. One might also point out that |592| in its individual parts and organization as well as in the meaning and spirit of the whole, this play is completely new, as even a brief overview will demonstrate. [Lengthy presentation of content.]

Here, then, one has complete harmony, complete satisfaction. The dispersed poetic sections in Euripides have been organized in part through invention, and in part through recasting of older material, into the totality of a true work of art.

By the way, the play has no chorus, and the dialogue is written in iambic pentameters interrupted by one hymn spoken by Ion in a choric meter borrowed from the Greek, then also by trochaic tetrameters in the tempestuous movement at the beginning of the third act, then anapests in the passionate monologue spoken by Creusa, and finally trimeters in lines of Apollo (everything with a purity and classicistic element as might be attained only by a poet bearing a spiritual kinship with the Greeks), all of which open up the prospect of future, more strict compositions after the model of the dramatic forms of antiquity. The unity of place and the constancy of time, both of which are of such importance for the simplicity of action, are observed without coercion and with ease and yet without denying the spectator a single necessary or more vivid view of the various individual occurrences. In his respect, the play accomplishes what the French tragedians were always aiming for but usually managed to accomplish only surreptitiously. Compared with their works with respect to elegance, it more closely resembles the works of the Greek tragedians as far as sheer energy is concerned. Given these superior inner characteristics, the performance of this play, under the direction of a master such as Goethe, could not fail to have the most unblemished and pleasing effect.

IV. The Berlin Performance of Ion

In the meantime, the Berlin performances of the play on 15 and 16 May 1802 had taken place (Wilhelm probably attended with Caroline and Schelling, who were in Berlin at the time), though there was never any performance in Vienna (see Wilhelm Schlegel to Goethe, on 19 January 1802 [letter 341a]). August Wilhelm Iffland, in a letter to Franz Kirms on 6 February 1802, [43] initially rejected both Ion and Schiller’s Turandot, for which he also had disdain:

Here is my opinion for you alone: Ion is a piece with much reason, no heart, and no really sophisticated understanding of propriety. — I will not take Thurandot at all, for that would be to mock good taste . . . .

Wilhelm negotiated long and hard concerning the stage set for the Berlin performance, exchanging several letters with Iffland, e.g., acknowledging on 6 February 1802 his own authorship of the play, agreeing on 9 February 1802, not to publish the piece before the Berlin performance, and receiving a letter from Iffland on 4 March 1802 in which the latter alerted Wilhelm to the probability that the play would be performed in late April or early May and offering to set up a meeting with the set designer. Wilhelm responded on 3 April 1802: [44]

Since your esteemed sir, in your missive of 4 March, expressed an inclination to accord my suggestions concerning the set of Ion a certain measure of influence, and because I believe a drawing would make my thoughts clearer than any verbal description, I spoke to a friend who is an architect with considerable learning and acumen. The latter did much more than I dared wish, presenting me with not only an outline sketch, but also a precisely rendered illustration with regard to which nothing more is left to do besides execute the plans themselves.

Several artists have as a favor offered to implement a beautiful set for Ion. The trees and background landscape for the set have been painted by a well-respected landscape painter, and the bas-relief for the fronton on a separate page came from the hand of a sensitive sculptor.

You will easily discern the hand of a master in the entire conception and organization, in the pure architectonic style, and finally also in the illumination and disposition of the set as a whole. It is not only wholly correct and internally coherent, which in itself is a rarity, but it also provides a completely beautiful, picturesque view, and consistently exhibits a meaningful relationship with the play itself, thereby contributing considerably and with clarity to an enhancement of the action, in which regard I commend to your attention the enclosed remarks [presumably the “Annotations concerning the Set of Ion and its Implementation”]. Since the scenery in Ion does not change, its rendering is, to be sure, of considerable importance; all the less difficult is it, however, to make the necessary arrangements. I naturally reserve ownership of the drawings for myself and also request they be returned after serving their purpose.

I have also enclosed drawings of the lyre, the flower basket, and Ion’s cradle. I will very soon also return the costumes to Herr Pauly, which he has just been so kind as to send me at my request. They are adequate for their purpose, since the colors have been more faithfully maintained than in the extremely bad copper engravings in the Modejournal [Journal des Luxus und der Moden 17 (1802) March, included in Goethe’s article “Weimarisches Hoftheater”; see above], albeit with respect to the drawing only bad copies of the originals provided by the theater in Weimar. The artist will be staying here another two weeks and is certainly willing to give advice should doubts arise concerning the cut of the clothes and the manner in which they are to be worn.

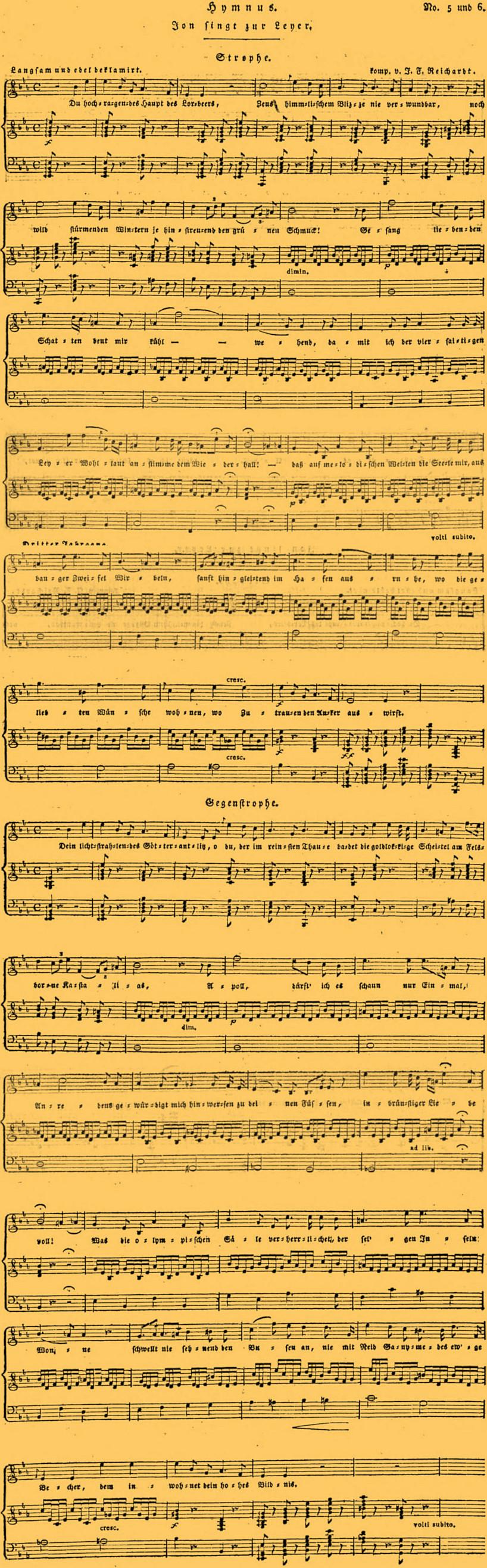

Herr Music Director Reichardt has told me that while reading through the manuscript he noticed various copying errors that distort the meaning; hence I would very much like to receive that manuscript that I might read through it and remove such errors as well as add a few altered passages provided by Goethe which I would like to incorporate.

As far as possible abridgement is concerned, approximately 20 verses could be deleted from Xuthus’s long narrative without creating problems with cohesion, though I would be disinclined to do so because this discourse falls precisely to you yourself and thus will doubtless be rendered with both clarity and emphasis. Creusa’s monologue might also be shortened by as much, though I believe one would thereby be treading a perilously close to the actress’s own art, since such can develop precisely in the alternation of passions in that discourse.

If you are disinclined to supervise a reading of the entire piece by the cast, I offer my services in that regard. Perhaps such might be of some use particularly as regards the passages written in unusual meter.

I have the honor of offering my complete respect as your esteemed sir’s

Most devoted

A. W. SchlegelBerlin, 3 April 1802

The architect and art critic Hans Christian Genelli designed the sets in Berlin, in which regard Friedrich Tieck writes from Berlin to Goethe on 3 April 1802: [45]

[Wilhelm] Schlegel sends you his devoted regards. Ion has not yet been performed here because so many other plays were already scheduled. But it will be performed during the first few days or first half of next month. The architect Genelli, whom you already know in various other capacities, drew a set decoration for Schlegel that possesses considerable value as an architectural piece quite apart from its handsome effect as a painting. One can thus hope that the piece will be performed here in Berlin with a considerable degree of perfection in this particular regard. This set genuinely was quite necessary for Berlin, since the inferiority and stupidity of the theater painter here is truly indescribable.

Genelli was quite dissatisfied with the implementation of his plans: [46] “As far as the set is concerned . . . Its implementation [according to the design] was admittedly so inferior as to be beneath criticism.”

After some initial, somewhat pointed comments concerning only the anonymity of the author, the journal Der Freimüthige (1802) 7 (15 August 1802) speaks in a strikingly positive fashion about the “wonderful gift” of this author who, “when he so desires and when literary partisanship does not blind him,” can function as an appointed mediator.

Although the journal Brennus. Eine Zeitschrift fur das nördliche Deutschland (Berlin 1802), 1:670, calls the Berlin performance exemplary (role assignments: Ion: Friederike Unzelmann; Creusa: Henriette Meyer; Xuthus: Iffland; Apollo: Franz Mattausch, whose “dialect astonished, truly not Attic at all”), it nonetheless reproached the piece as “an extremely boring product of the new school,” also chastising Apollo’s and Xuthus’s amorous inclinations as nothing but “momentary animalistic pleasure . . . the aberration of a couple of dissolute fellows who stray into a brothel.” And indeed, at the initiative of her spouse, Henriette Meyer declined any further appearances in the “offensive” role of Creusa.

V. The Scandal Surrounding Creusa’s Monologue in act 4, scene 1

Some viewers — including Henriette Meyer’s husband, as just seen, who forbid her from performing the role again [47] — found certain elements in Creusa’s monologue offensive and even indecent. Such include especially the allusion to Ion’s concealed lineage from the god Apollo, who begot him with Creusa in a cave sixteen years before the play takes place, and to Xuthus’s affair with a bacchante following a drunken celebration of his own heroic deeds, also sixteen years earlier, prompting him to believe a false prophecy indicating that Ion was in fact his own biological son. Creusa exposed Ion after giving birth and concealed her tryst with Apollo later from her husband, Xuthus, then tries to kill Ion as part of the action of the play after Phorbas convinces her Ion is in fact the son of the bacchante, the latter of whom, if found, would eventually replace the seemingly barren Creusa in the household.

In the middle section of her monologue, Creusa laments her seduction by Apollo and her exposure of the infant at the shrine of Apollo:

Act 4, scene 1

Creusa. So be it, I can endure it no longer.

O this fear is thousandfold death!

I would rather offer my neck to him here,

That with a single blow he swiftly strike

And free me from this torment and shame.

An interminable hour have I to and fro

Covertly wandered about, trembling, like a hind

Who hears the young lion’s roar.

I heard him roaring, beseeching forest and cliff

To betray where concealed I did lie,

On whose head he did pour every god’s curse.

Round about did the echo double

The pursuer’s voice, and then did call out

To him his companions: Ion! Ion!

As if that name were the hunting cry

Wherewith from every side they did terrify me.

Finally did I pull myself up, daring

To venture forth in the light of day.

What might I be risking? Alas, Creusa!

Wretched, despairing woman!

After what you have done, and suffered,

Is anything yet left for you in the world

But to endure your death with matching courage?

How is it that cowardice now seizes you?

But no! Let me not falsely accuse myself;

It is not death whose gaze I shun,

But that it be the youth’s own hand that offers it to me,

That, that is what I cannot overcome,

Thus does madness drive me in confusion forth;

And though with swollen pride I did try

My breast from within to harden

As often as I did expose it to the arrow,

Yet did dissolve the aegis of cold hard courage

Into fear and gentle hope in life.

Let us see whether this sanctuary might shield us.

But how? Its occupant himself does pursue me.

Nonetheless this seat will I choose,

Awaiting here my fate, in inextricable

Embrace, my arms around the altar.

(She sits down on the altar steps and embraces it.)

And if I must die, then shall at least

My blood stain this place of sacrifice,

So dreadfully indeed that never again

Shall incense, nor purification, atone it clean.

Through the heavens shall my final cry

Penetrate to the blessed seat of the gods,

So heart-rending that he who brings my ruin cannot but blanche.

Thus the woman’s sole vengeance:

Helplessly and mortally to breathe out

Her wretched soul before the very countenance of her destroyer.

Woe! Thus do you reward your beloved, Apollo?

O how different your earlier vow to me,

When as an unsuspecting child of virginal step

I did wander alone on springtime meadows,

Gathering into folded cloak the colored brilliance

Of flower and leaf,

When you did appear, gracious and grand,

With head of golden locks, in ambrosial fragrance,

Smiling in eternal youth and beauty,

Then with sweet flattery did you seize my hand

Such that the flowery treasure, innocently lamented,

Did tumble from the bosom of the, alas! resisting girl.

Gently did you call to me: “Nymph, fear not! let

Wilted adornment disperse on the ground,

For in sweet profusion even on your own lips

Do the scarlet blossoms of desire now swell,

Newly budding as often as does a kiss pluck one.

Impede not their flourishing, and behold, how comely

The immortal garland love now weaves of them.”

Thus did your words, intoxicating illusion, envelope me,

Nor did help my impotent cries, as quickly

Into the cave of Pan you did draw me.

Woe, woe to you, O day! O secretive bed,

Divine embraces, pregnant with baleful menace!

Woe, and woe to you all!

As a sea rages wild, so did quickly beset me

Dreaming ruefulness, languishing grief,

Blushing awe, paling fear.

Nor succor from woman’s hand did the orphan have,

Silently did I, alone, carry the burden of the secret,

Of the life that seemed to promise me death, —

Whose mouth does speak from the mother’s distress in birth,

Abandoned by gods and mortals alike?

And then, O shame! like crime and rape

To deny Apollo’s sacred offspring!

O knowing crevice, whither I did carry him,

To the very bed that once gave him life,

Silence and darkness, accomplices alone!

Witness my endlessly suffering lament,

For indeed did you hear it when the infant boy did

Stretch out his hands to me, desiring the very breast

That forever did cruelly tear itself from him.

Yet thus did I leave him them, like a precious pledge,

Not like a uselessly burdensome possession

That in haste one casts aside in the street;

Wrapped in swaddling clothes, which I myself did stitch,

Oft sprinkling them with tears while at work.

And many a precious piece did I leave with him,

And the serpents of gold, document of his sublime lineage,

Which even me did once guard in the cradle.

But you, Apollo, did neglect him,

Ungrateful to the bed of love, and to me,

As not even the coarsest barbarian would have done;

To the predators of the forest did you surrender your child.

And to the birds of heaven as a banquet,

Whilst you, at ease in serene Olympus,

Binding the grape-laden locks of your hair

Commence the zither’s genial play,

Soothing with song the melodic heart.

And leading the muses’ immortal chorus.

And more yet! When I, long childless,

Did finally put aside just pride

And seek at the oracle counsel and comfort,

The great god now decides to do away with me,

Since my presence does now shame him here.

To the spouse whom I did tolerate to join

He now appoints as son, as temple servant,

Whom I with pleasure did foolishly behold,

Who with flattery alone did pry my trust.

But soon did Phoebus appoint him my slayer,

And then leave over, like a target too small,

The once beloved breast to the false boy.

O all-too-disgraceful humiliation!

Am I not worth even one of your arrows?

Here I sit, defying your anger:

Slay me with your lightning projectiles,

Compassionately, and end my torment!

For everything Niobe once felt

When you strangled a nation of her children,

Cruelly leaving not a single one,

Do I now feel for the infant, your son.

Alas, that mere thought turns me to stone!

The hard marble does already falter in my heart,

And makes it way, icily, through all my members.

If I do call in vain for quick death,

Then shall my eyes keep this entrance,

As if gazing into your countenance,

Till I turn into tearful stone,

A monument to your love, to your lust!

(Falls in exhaustion.)

In addition to Genelli’s account of the scandal concerning Henriette Meyer (Genelli spells it “Mayer”) and the role of Creusa, see also the letter of a certain Herr von Redtel to Johann Friedrich Reichardt from Berlin on 8 June 1802: [48]

There can be nothing more regrettable than that the performance of this play now be denied us for so long, perhaps forever. Perhaps you already know that Herr Meyer has reservations about allowing lines as allegedly indecent as those in Ion to continue to be uttered from the mouth of his wife; a considerable part of the public agrees with him, and since the piece is viewed as being boring in any case, castigating it as immoral serves as yet another means to deliver it over to obscurity. Iffland is currently away on a journey, so any efforts on behalf of the play are for now quite fruitless. Let me implore you to exercise whatever influence you have over Iffland in prompting him to break Meyer’s stubbornness (even in a larger sense such recalcitrance is a threat . . . to the theater) or to fill the roles otherwise as effectively as possible to avoid denying us such excellence.

This view of Ion is reflected in Karl August Varnhagen von Ense as well: [49]

[ . . . ] here, too [in Wilhelm Schlegel’s Ion], his opponents had to acknowledge its considerable merits while secretly delighting that the physician Dr. Heinrich Meyer intended no longer to allow his wife to perform the indeed ambiguous role of Creusa, thereby thwarting for good any further performances of the piece, which had in fact been received with considerable applause.

Wilhelm, however, had a quick opportunity for revenge in a review of the play Rollas Tod: [50]