August von Kotzebue’s Hyperborean Ass and the Schlegels

August von Kotzebue, Der hyperboreische Esel oder die heutige Bildung. Ein drastisches Drama, und philosophisches Lustspiel für Jünglinge, in einem Akt (Leipzig 1799); reprint: Deutsche Litteratur-Pasquille 3 (Leipzig 1907).

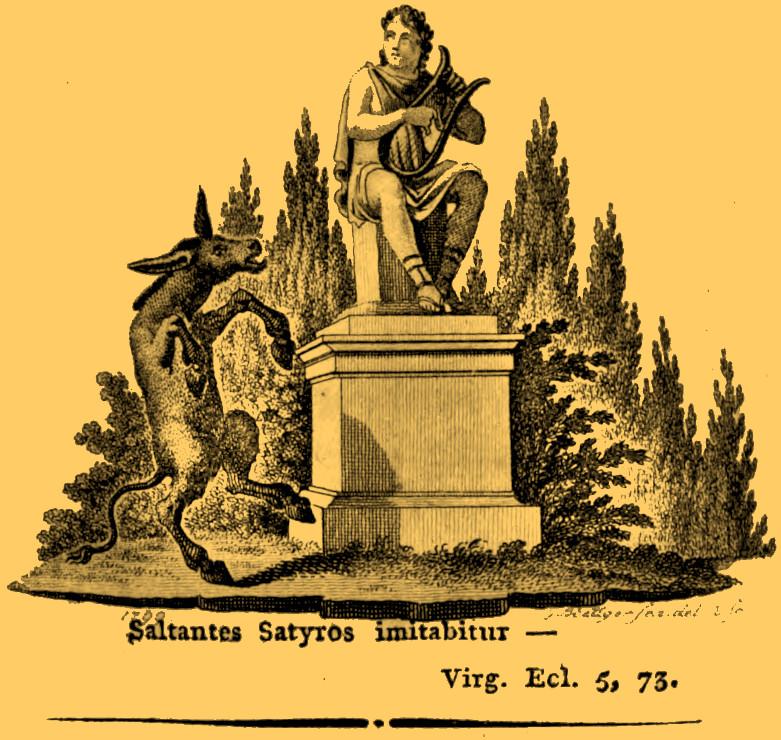

The title and vignette were modeled after Wilhelm Schlegel’s fragment in Athenaeum (1798) 228 (original pagination: 52): [1]

Hardly any literature other than ours can exhibit so many monstrosities born of a mania for originality. Here too are we proved Hyperboreans. For among the Hyperboreans asses were sacrificed to Apollo, who would then take delight in their marvelous leaps.

(The appended quote from Virgil [Eclogues 5:73] refers to “imitating the leaps of the satyrs.”) [2]

Concerning the play’s story, see “Occasional Retrospect of Foreign Literature,” The Critical Review; or, Annals of Literature, vol. 28 (1800), Appendix: Foreign Articles, 545–72, here 570–71:

Der Hyperboreische Esel, oder die heutige Bildung; von A. v. Kotzebue. The Hyperborean Ass, or Modern Education, a Philosophical Comedy for Young Men, in One Act. 8vo (Leipzig, 1799). —

The universities of Germany are overrun with a strange pedantic sophistry and unmeaning jargon, miscalled philosophy. To ridicule this abuse of time and learning, a young man who has studied philosophy under Fichte, morality under Schlegel, and history under Schiller, is brought upon the stage. His widowed mother, uncle, and intended bride, are prepared to adore this prodigy of learning; and a brother who had lived in the country, employed in rustic sports and business, is not a little ashamed of his own ignorance.

But the mother is almost distracted at the first conversation with her learned son, as all his answers are taken literally from the books of the new German school, and she finds him a wretch without feeling, without virtue, full of pride, folly, and atheism. The baron his uncle afterwards converses with him, and is astonished and shocked when the nephew denies his existence. The intended bride cannot reconcile to herself his jests upon chastity, or his proposition that marriage is mere concubinage, and that marriage a quatre would be an improvement. The rustic brother has time only to make excuses for going away to meet the prince, who was to hunt in the uncle’s woods, where he fortunately defended the prince against an attack of a wild boar.

The prince now appears, and converses with the young pedant, whom he finds incapable of filling any office in his dominions, and fit only for an hospital of lunatics. The play ends with the appointment of the young rustic to the mastership of the forests, and his acquisition of the fair one who was intended for his brother.

The species of ridicule introduced into this play may be useful in Germany; but in England it would be difficult to find a single young gownsman so stupid as to weary his relatives or friends with extracts from college lectures: we are apt in this country to run rather into the contrary extreme. We may add, that the exquisite wit of Aristophanes in his Clouds forms a striking contrast to the plain phlegmatic style of the German dramatist.

Kotzebue’s satire arguably represents an iteration of the many satirical takes on the notion of the “dreamy poet” with his head in the (fantastical) clouds rather than in the real world (Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, Der Dichter [1780]; Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Chodowiecki Sammlung [4-209]):

Kotzebue comically pieces together the discourses of the young “fool” Karl in the play from Friedrich’s (and Wilhelm’s) actual fragments; see his preface to the play (p. 18):

The role of Karl has been drawn solely and completely, moreover verbatim from the familiar and famous writings of the Schlegel brothers. All the golden maxims of these wise men have been assiduously stressed, in part lest one believe I am trying to adorn myself with someone else’s quills, in part because — as one of their own golden maxims maintains — everything must be stressed in true prose.

An example of Karl’s philosophical foolishness can be seen in scene 8, in which Karl and his love interest, Malchen (Amalie), appear: [3]

Karl (hastens toward her, then pulling her to his breast). Ha! my Amalie!

Malchen Easy! Easy, my dear cousin! You’re suffocating me.

Karl. There is essentially and congenitally in the nature of the male a certain doltish enthusiasm that readily is godlike almost to grossness. (Tries to embrace her again.)

Malchen (abashed and resisting). Not so impetuous, my dear Karl.

Karl (smiles and observes her). Being an innocent girl really puts one in a funny situation.

Malchen (astonished). What? a funny situation?

Karl. Absolutely, though women will probably have to remain prudish for as long as men are sentimental, stupid, and bad enough to demand eternal innocence and ignorance from them.

Malchen. So you are not demanding innocence from me?

Karl. You are a lovely young girl and thus

the most charming symbol of pure good will. Malchen. A strange compliment.

Karl. We will marry.

Malchen. Perhaps.

Karl. It is true, women have absolutely no sense for art, no talent for science, no sense for abstractions, and wanton malice, combined with naive coldness and laughing insensitivity, are the congenital art of women.

Malchen. What a flattering portrayal!

Karl. And yet I am resolved to make an attempt.

Malchen. An attempt? Please do.

Karl. Almost all marriages are simply concubinages, rather provisional experiments of a true marriage.

Malchen. Cousine, I hope I do not understand you.

Karl. We could even push this wish to the extreme, for example, with a marriage à quatre.

Malchen (almost speechless in astonishment). Excuse me?

Karl. It’s hard to imagine what basic objection there could be to a marriage à quatre.

Malchen. You would really be willing to share your beloved?

Karl. I will endeavor to possess you as if I did not possess you.

Malchen. A pleasant prospect!

Karl. A cynic should really have no posessions whatever.

Malchen (with increasing impatience). My dear cousin, you will probably not possess me at all.

Karl. What, Amalie? Have you already forgotten the wonderful times of the most beautiful chaos of sublime harmonies and fascinating pleasures?

Malchen. That now seems to have turned into a chaos of dissonances.

Karl. What displeases you about me?

Malchen. Your complete lack of delicacy.

Karl. Cute vulgarity and refined bad manners are called delicacy in the language of good society.

Malchen. And your immorality.

Karl. Why shouldn’t there be immoral people as well as unphilosophical and unpoetical ones?

Malchen. You propose a marriage à quatre to me like a game of whist.

Karl. Well, yes.

Malchen. Did it ever occur to you what the rest of the world might think about that?

Karl. To disrespect the masses is moral. etc. etc.

Karl’s exchanges with the prince are similar, with only the subject matter changing from love and morals to political issues:

Prince. I can now see where this conversation is headed. Let me give you some well-meaning advice, namely, not to have anything to do with state administration, at least not in my own land, where peace and morality rule.

Karl. Morality? I hardly believe that. The first impulse of morality is to oppose positive legality and conventional justice.

Prince. That sounds quite like the utterly destructive principles of more recent times.

Karl. It’s natural that the French should more or less dominate the age. They are a chemical nation; likewise, the age is also a chemical one.

Prince. Even better.

Karl. The French Revolution, Fichte’s philosophy, and Goethe’s Meister are the greatest tendencies of the age.

Prince. Well, I think I have heard enough. But I still do not know what you actually learned.

Karl. I understand art. I know how Diderot sets paintings to music.

Prince (smiling). Go on.

Karl. I have a theory ovarium in the brain and, like a hen, lay a theory every day.

Prince (growing impatient). But what position are you capable of holding down?

Karl. I merely wish to be tolerant.

Prince. Tolerant? I know of no such position.

Karl. Tolerance means being almost unaware of being free in all directions and from all sides; means living one’s whole humanity.

Prince. You poor dreamer! No one can do that who is a member of society, which demands that he be industrious and useful.

Karl. Industry and utility are the angels of death who, with fiery swords, prevent man’s return to Paradise.

Prince. Great heavens! What an abominable assertion!

The prince finally has enough:

Prince. Young man, I am going to send you to the insane asylum for a time, also requesting that you, sir, by virtue of your bold arbitrary powers, view this insane asylum as poesy.

Karl (proudly exiting). The life of the Universal Spirit is an unbroken chain of inner revolutions; all individuals — that is, all original and eternal ones — live in him. He is a genuine polytheist and bears within himself all Olympus. (Exits.)

Ludwig Ferdinand Huber seems to have been the reviewer (see Caroline’s letter to him on 24 November 1799 [letter 257]; see also her letter to Johann Diederich Gries on 27 December 1799 [letter 258]) who, albeit without mentioning the Schlegels, found the play’s wit somewhat “wanting” in the review of the play in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (1799) 415 (Saturday, 28 December 1799) 822–24:

Literary satire can be directed against a school, against the public’s own errors of taste, or even against popular writers. Thus [George Villiers] Buckingham’s Rehearsal [1672; a parody of heroic plays that similarly strings together passages] was a masterpiece of this genre in its time, and even today continues to maintain its status, a century and a half later. Thus also do Tiek’s grotesques deserve more general approval among us than they can expect to receive given the circumstances of our own literature.

Satire can then also demonstrate primarily the merit of pure willfulness, and in this respect the name Tiek once again suggests itself to the impartial critic; in that case, it approximates more closely the genre of French parodies, which never detract from the value of the works they parody.

Satire can also, as in Liscov’s, Pope’s, and Rost’s works, pass judgment on presumptuous foolishness, intolerance, and lack of taste. And, finally, it is often enough, as in Voltaire, Palissot, et al., the instrument of literary factionalism. It admittedly almost always has a bit of the latter, of course, insofar as the angels in heaven are not wont to write satires.

But just as pointed wit and comic talent always lend it higher value regardless of the source from which such may flow, so also can the disposition of the objects on which it practices its craft, be they ever so suited for satire as such, not excuse the lack of pointed wit, or of comic talent.

Herr von Kotzebue doubtless has more wit at his disposal than he saw fit to offer up here; that he was overly considerate in this respect here seems to derive from the notion that the passages he has the character of Karl speak were already in and of themselves so ridiculous and comical that he could put the weight of his entire satire on their shoulders.

But by being satisfied with juxtaposing these passages with ordinary life, he in fact fell well short of the demands made of literary satire. These passages are admittedly also ridiculous here; but if they are indeed more ridiculous here, are they then ridiculous in a different fashion than in the writings from which they were drawn?

Instead, through that particular contrast, passages that would not have been ridiculous could be made ridiculous or comical, and such would indeed have accorded with the innocent genre of the French parody. If one has a young man, amid the utterly normal circumstances attributed to the protagonist of this drastic drama [the subtitle], speak no other language than the most beautiful language of our best writers and philosophers, that language will genuinely be funny.

For precisely that reason, however, the gibberish spouted by this or that philosopher or writer in our age that disdains all healthy human understanding, by being placed in the mouth of a young man in those particular circumstances, is in fact not being satirized at all. And if one is supposed to laugh at such language, regardless of where it may be spoken, then Herr von Kotzebue has contributed too little of his own wit for the entertainment of his readers to prevent whatever gratitude he may receive from legitimately and by all rights being sent back to the proper authorities.

Insofar as, by contrast, Herr von Kotzebue, through his adventurous clichés, compromises his protagonist in this piece with pious and princely persons, he doubtless has not considered that under present circumstances such can all too easily turn into something more than satire.

It is perhaps Kotzebue himself who challenges the reviewer on various points in the Intelligenzblatt of the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (1800) 18 (Sunday, 8 February 1800), 142–44; the (still anonymous) reviewer responds in the same issue.

Notes

[1] Reprinted in Friedrich Schlegel, Jugendschriften, 2:234 (not 2:134 as in Schmidt, [1913], 1:748), fragment 197; trans. Friedrich Schlegel’s Lucinde and the Fragments, trans. Peter Firchow (Minneapolis 1971), 188. Back.

[2] See esp. the team of “Hyperborean asses” pulling the carriage of Romantic aesthetics in Kotzebue’s 1803 caricature “The Most Recent Aesthetics.” Back.

[3] Trans. of Athenaeum fragments and passages from Lucinde from Friedrich Schlegel’s Lucinde and the Fragments, trans. Peter Firchow (Minneapolis 1971). Back.

Translation © 2013 Doug Stott