• 67. Caroline to Lotte Michaelis in Göttingen: Clausthal, 20 March 1786

Clausthal. Monday evening [20 March 1786]

|143| I almost think I watch winter arrive here with an even lighter heart than I do spring. Winter may well be raw sometimes, and nature herself impoverished and cold. Moreover, for half the day I see nothing of nature then in any case, and for the other half am able to be myself, undisturbed, here in my room. But springtime always makes me homesick; it is always the season of sweet melancholy; but, as there is no occasion for a sweet one, [1] it turns bitter.

But who knows which thousand little things are making me dissatisfied this evening, things having nothing to do with the warmer sun. I myself do not even know. My own burdensome weight is oppressing me. It always happens that if I have not thought about myself for a long time and then do indeed stop and conduct a révue, it just seems that so much needs improvement, my more noble activities have become so lethargic and limp, and in such situations, at least if one is impartial, one then finds that practically everything that makes us ill-tempered is indeed a result of our own lack of precisely such activity. Things do get better afterward — one is better — |144| until one sinks down anew — and lifts oneself up anew.

I am glad I will soon be able to perceive that first improvement; but it is because I know how easy it is to be blind even with eyes wide open that I so often take the opportunity to warn you, my dear sister, something you may not hold against me, since doing so would change nothing, I will not cease to remind you as long as your own fate is still so uncertain. I have no intention of tormenting you, I would just like for your pleasures to seem a bit shaky now and then lest the security of their enjoyment lead you too far astray. I have, after all, expressed no displeasure at all otherwise. Only always be cautious in the face of the wicked world; I cannot really see how that can still come about considering how willful you all are, and yet so much depends on precisely that. [1a]

On Wednesday we were yet able to take a lengthy sleigh ride to which Madam von Reden had invited us. We departed from in front of the mining administration building, 17 sleighs in all, though the procession was admittedly not as impressive as when lead riders are bearing flags. [2] The truth is, we did not have any lead riders, and the sleigh équipage [team] here, especially considering how often one travels by sleigh, in general leaves much to be desired; for example, there are never any feather tassels on the horses, and when one with tassels did recently pass by with an out-of-towner, the ladies talked about it like in the story of the green ass. [2a]

But in return, our ride was the most charming imaginable, taking us through a valley and through an avenue lined with green fir trees that always look quite green close up but then dark from afar. [3] The weather was excellent, and in 3/4 of an hour we arrived at a newly built house in the middle of the forest. There we found music and a magnificent spread of food and drink, everything one could possibly desire; indeed, we stayed even into the evening, and it was Madam von Reden herself who had taken everything out there, even down to the silver candelabra and wax candles. Toward evening |145| we played vingt-et-un for rather high stakes, Madam Reden doubtless losing 3–4 louis d’ors. I quit because I did not want to bet so high, and betting lower tended to be boring by comparison. [4] We spent our time quite tolerably; I spoke with Usslar [5] from Göttingen for quite some time, who is not a bad fellow at all. Madam Reden was — and wanted to be — a very good hostess indeed. Her husband was away on a trip. . . .

22 March

I really should not have written so much the day before yesterday, since the Donna is not leaving until tomorrow. [6] She will be fairly washed hither by the rain; today we had quite respectable thunderstorms, and at sunset an illumination as magnificent as any the sun can offer up. But I for my part am not well, I would rather stick the feather under my nightcap than hold it between my fingers — as a matter of fact, this desire is becoming so strong in me that I must give in to it — and take leave of you for now.

Just this one thing yet: have you nothing for me to read? I have been withering away for some time now because all my book sources are yielding nothing. Marianne sends nothing — Blumenbach is being Papa Johannes [7] — I have canceled my purchases with Madam Volborth [8] — and you? So I am like the person who wanted to invite all these guests, and then they all excuse themselves. Sans comparaison [9] with the blind and the lame, I have now asked Meyer, first, for something entertaining and good one can read while reclining on the sofa. It must not necessarily be an oversized tome, but something one can hold in one hand.

I would really like more recent French tragedies, short novels, mémoires, or even something more serious. God! surely he knows what I mean. I welcome anything I have not yet read. Second, I would like something one can read while sitting on the sofa before a table, something like older English history from the age of Alfred; and volume 4 of Plutarch [10] |146| (I have already read the others). I do not want everything at once.

At the next opportunity I will read Win[c]kelmann and Ossian again. [11] Please do spend a bit of time taking care of this for your sister; it really is irresponsible how indifferently everyone is letting me turn into Cinderella. [11a] Make sure Meyer knows how important it is. If I do not receive anything, I will no longer believe in your power over him. [12] That threat at least should show you how serious is my request for reading material. [13]

I really do feel out of sorts. I have to get undressed. Stay well, my dear; love me, follow me, and care for me.

Caroline

Notes

[1] Italicized expression in English in original; unknown provenance. Back.

[1a] Caroline is once more in her advice mode with Lotte (Göttinger Taschen Calender für das Jahr 1793; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung):

[2] Illustration: Almanach der Musen und Grazien für das Jahr 1802; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung:

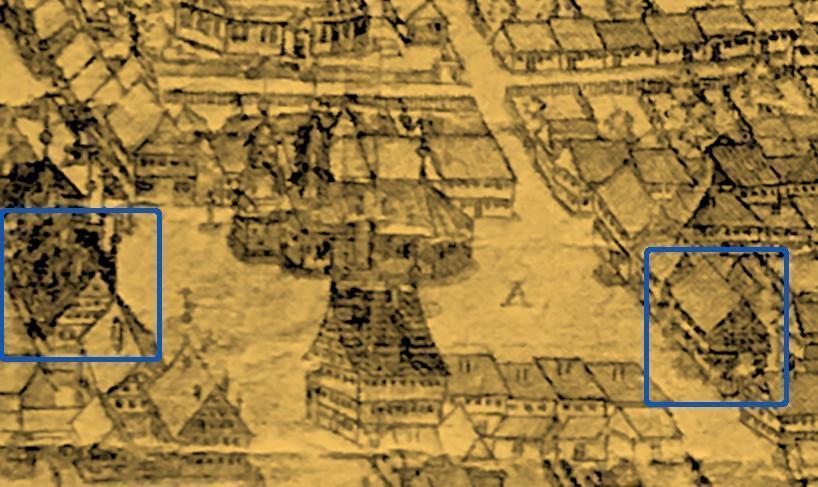

The mining administration building, today the State Office for Mining, Energy, and Geology, was formerly Claus Friedrich von Reden’s office on the main square in Clausthal and directly across from the Church of the Holy Spirit and Caroline’s residence. The administration building is in the center background of this early postcard, the town hall visible just behind the church tower:

Here the town square from the other (southerly) direction with the administration building on the west side of the square, the town hall on the south side at center bottom, and Caroline’s residence on the east side (Adam Illing, Der Marktplatz von Clausthal im Jahre 1661, repr. in the Allgemeiner Harz-Berg-Kalender für das Schaltjahr 1928 [Clausthal 1928], 43):

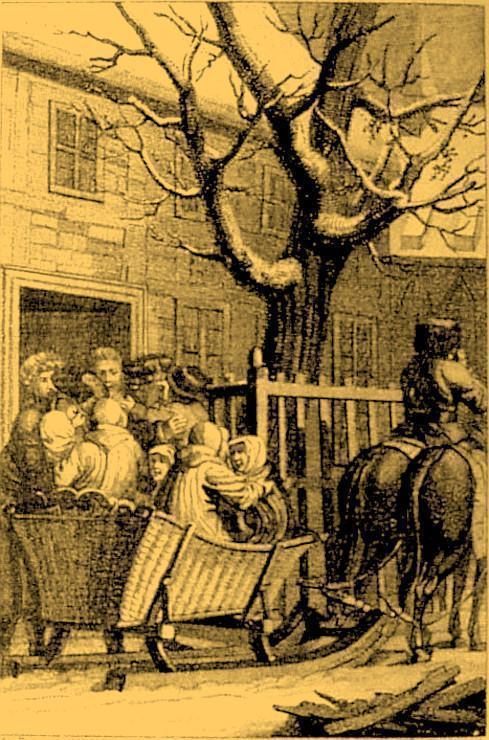

Here the commencement of a sleigh outing on a similar town square (here in the university town of Halle) (R. Fick, ed., Auf Deutschlands hohen Schulen: Eine illustrierte kulturgeschichtliche Darstellung deutschen Hochschul- und Studentenwesens [Berlin, Leipzig 1900, 386):

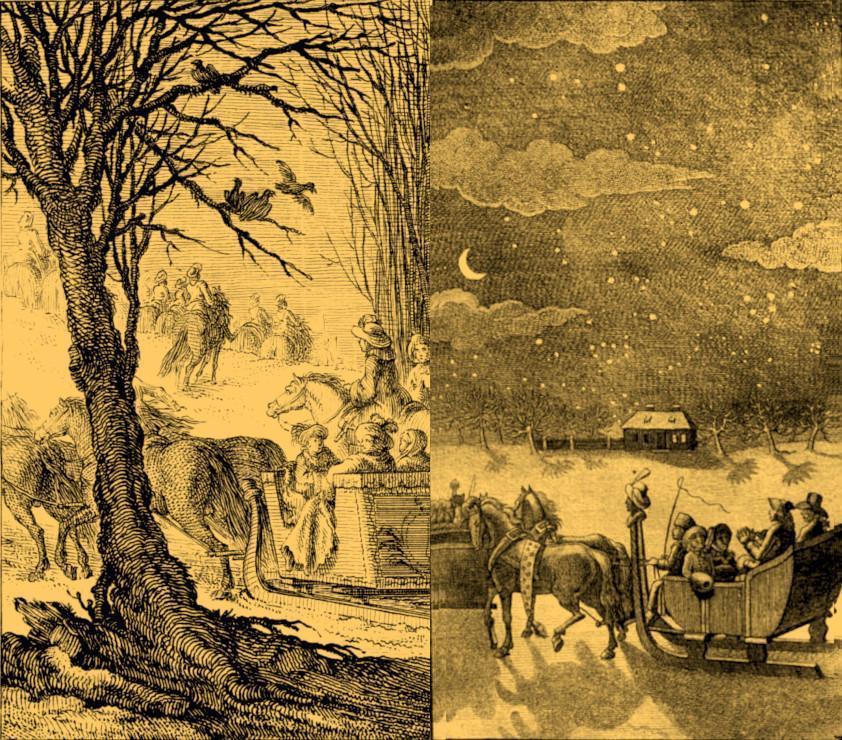

See the following illustrations of such a sleigh outing from 1792 (Johann Wilhelm Mein, Schlittenfahrt [1792]; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur JWMeil AB 3.205), 1787 (at night, as Caroline goes on to mention; Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, Kupfer zu Herrn Professor Salzmanns Elementarwerk nach den Zeichnungen Herr Daniel Chodowiecki, nos. 1, 2 [Leipzig 1787], plate lxi), and esp. the 1902 postcard of Clausthal students preparing for a sleigh excursion and processional as part of Carnival festivities quite similar to what Caroline here describes:

Here an illustration of a student sleigh outing in Jena ca. 1700, where beginning in mid-1796 Caroline herself will live (Georg Steinhausen, Geschichte der Deutschen Kultur [Leipzig 1904], 531):

[2a] Here a sleigh with a more elaborate ornamentation and a lead rider (Taschenbuch für das Jahr 1822: Der Liebe und Freundschaft gewidmet; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung):

Various versions of the story of the “Green Ass” exist, one of the earliest being the simple version in Aesop (“Of the Widow and the Green Ass”). The popular version in German was by Christian Gellert (text see supplementary appendix 67.1). Back.

[3] The Harz Mountains richly attest the sort of forested roadways and paths Caroline here describes; because in her letters Caroline otherwise rarely expresses much enthusiasm for landscapes, this passage is worth noting. Here an early postcard of what is known as “Goethe’s Trail” in the Harz Mountains moving toward the Brocken:

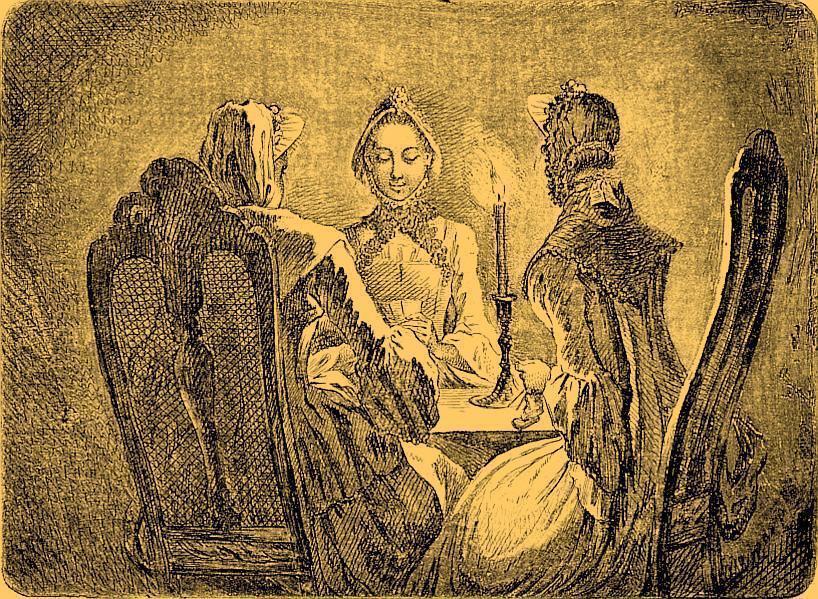

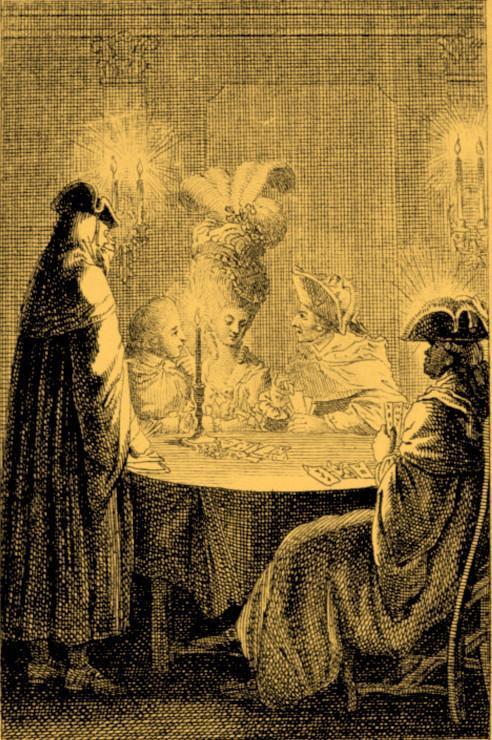

[4] Vingt-et-un, blackjack. With regard to card playing in general, see esp. the custom deck of playing cards published by Johann Friedrich Cotta in 1804. — Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki did a series of vignettes in 1780 with the title Occupations des dames; one of those vignettes, “Gaming,” features five persons playing cards at a table during the evening, possibly whist (Das Spiel [1780]; Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Uh 4° 47 [156]); a second engraving from a different collection features three women playing the card game l’Hombre; and two general gaming illustrations (Sammlung eine ehemaligen Professors der Berliner Akademie und Wiener Adelsbesitz: Kupferstiche Radierungen Holzschnitte Lithographien Farbendrucke Schaabkunstblätter des XVI. bis XIX. Jahrhunderts, Kunstauktion v Hollstein & Puppen, Versteigerung zu Berlin [9 March–12 March 1914], 9; Amusement innocent; Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Uh 4° 47 [213]; Kandide im Spielsalon; Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Museums./Signatur Uh 4°47[88]; Gesellschaft beim Kartenspiel, in Chodowiecki, Künstler-Monographien, ed. H. Knackfuss xxi [Bielefeld, Leipzig 1897], 15):

Here a gaming table from the periodical dedicated to such entertainment (Berliner Almanach für Karten- Schach- und Pharospieler [1805], Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung):

There were, of course, more satirical takes on the ills and risks of gaming (“Der Pharaotisch,” Taschenbuch auf das Jahr 1803: Dem Edeln und Schönen der frohen Laune und der Philosophie des Lebens gewidmet [1804], plate 3):

[5] Possibly the forestry botanist Julius Heinrich Uslar. Back.

[6] Presumably the messenger woman. Back.

[7] “Papa Johannes,” Gevatter Johannes: “Gevatter,” generally “godparent,” being colloquially also a form of address for friends and acquaintances, “Johannes” being Blumenbach’s given name (Johann Friedrich); Caroline is intentionally referring to Blumenbach in an ironic, piqued fashion for his apparent failure to address her book requests. Back.

[8] The Göttingen professor and preacher Johann Karl Vollborth, who together with his (according to Erich Schmidt [1913], 1:684) pretty young wife, Christiane, née Offeney, kept a quite sociable and musical house; he was also the head of a reading society in connection with which for a yearly fee of 5 rh. a member received 2–3 new books twice a week; see Pütter, Gelehrten-Geschichte, 2:390:

The convenience of reading several political and scholarly newspapers for a cheap price is provided not only by several newspaper carriers, who through a quarterly agreement will deliver whichever newspapers one chooses to one’s house for two hours, but also by several reading societies that have emerged to share the periodical publications that appear so frequently now.

Professor Volborth [Vollborth] manages such a reading society; for a yearly fee of 5 Rthlr. in gold he sends to every member two or three issues of periodicals or other noteworthy new publications every Monday and Thursday morning. The university apothecary Sander manages yet another society of this sort. In 1784 the antiquarian bookseller Schneider published his own catalog of a selection of German and French books along with the most noteworthy German periodicals as well as political and scholarly newspapers, the agreement being that they could in part be read in his house and in part be taken home by every participant for 1 to 3 days.

As obvious as is the contribution such institutions make toward satisfying this scholarly need of the age, particularly at a university, it is just as certain, on the other hand, given the proliferation of periodicals and other publications serving more for entertainment than scholarly instruction, that one cannot recommend too forcefully that young students ought at least exercise considerable caution, moderation, and abstinence with respect to this sort of reading in order not to take time away from other, more useful activities. Back.

[9] Fr., “beyond comparison.” Back.

[10] Caroline is referring to the different sizes of books at the time such as quarto and octavo and the attendent problems holding the larger formats comfortably (Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, Lesendes Mädchen, in Chodowiecki, Künstler-Monographien, ed. H. Knackfuss xxi [Bielefeld, Leipzig 1897], 95):

The following, on the other hand, is not exactly the sofa scene Caroline has in mind, but a good (if overtly satirical) illustration nonetheless of the use of a table and sofa together during the period; see note 13 below for an illustration of reading at a sofa without using such a table (illustration: Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, Familienszene, ca. [1770–1813]; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum Museums./Signatur DChodowiecki-Kopie Z AB 3.1):

Erich Schmidt (1913), 1:684, surmises that the reference is probably to vol. 4 of Biographien des Plutarchs mit Anmerkungen, translated by Gottlob Benedict von Schirach (Berlin 1778), rather than to Felix Nüscheler’s four-volume translation Moralia. Auserlesene moralische Schriften von Plutarch (Zürich 1768–74). Here the title pages to vols 1, 2, and 4 of Schirach’s edition:

[11] Johann Joachim Winckelmann, though the specific reference is unclear; perhaps his Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums, 2 vols. (Dresden 1764) or the popular piece Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerey und Bildhauerkunst, 2nd ed. (Dresden, Leipzig 1756); here the title vignette:

The second reference is to James Macpherson’s forged publications about the legendary Gaelic warrior Ossian, Fragments of Ancient Poetry collected in the Highlands of Scotland (Edinburgh 1760), Fingal (London 1762), and Temora (London 1763) (though the collection is often referred simply as Ossian), translated into German by Johann Nepomuk Cosmas Michael Denis as Die Gedichte Ossians, Eines Alten Celtischen Dichters, 3 vols. (Vienna 1768–69). The work allegedly reflected ancient Scottish Gaelic epic sources about a legendary warrior society’s history of war and love in a dark, forbidding, primitive Scottish landscape, and considerably influenced literature in both England and on the continent, including German Storm-and-Stress and Romantic literature.

Denis published a revised translation, Lieder Ossians und Sineds (Vienna 1784), after the appearance of Macpherson’s own second edition, and it is perhaps to this edition that Caroline is referring. — Here (1) the frontispiece to the translation edition of 1768 and (2) the title page to the edition of 1784:

Here several stylized illustrations reflecting the public perception of the Ossian epic, its characters, and its setting from vol. 2 of The Poems of Ossian, translated by James Macpherson, Esq., 3 vols. (London 1812), and vol. 2 (London 1795):

Here an illustration to “Selama, eine neuentdeckte, köstliche Reliquie Ossians,” by Freiherr von Harold, from the Bergisches Taschenbuch für 1800: Zur Belehrung und Unterhaltung (Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung), with the bard Ossian at left:

[11a] Caroline could have been familiar with this popular fairy tale from any of a number of sources during the late eighteenth century, though it may be pointed out that the Grimm brothers’ version was not published until 1812. One of the earlier versions during the century, and one that in its own turn drew from earlier Italian versions, was that of Charles Perrault with the glass slipper, from which the following illustration was taken and with which Caroline, with essentially fluent French and an appetite for French reading material from an early age, may well have been familiar (Charles Perrault, “Cendrillon ou la Petite Pantoufle de verre,” Histoires ou Contes du tems passé. Avec des moralitez, rev. ed. [Amsterdam 1742], 64–81, here 64):

[12] Concerning Lotte’s relationship with Friedrich Ludwig Wilhelm Meyer, see Caroline to Lotte on 18 October 1785 (letter 61) and Lotte to Caroline in November 1785 (letter 64). Back.

[13] Young girls in middle-class families were usually taught to read from a relatively early age, often by a tutor or governess, as seems to have been the case in the Michaelis family, or directly by a family member (illustrations [1] Johann Friedrich Cotta, Taschenbuch für Damen auf das Jahr 1800 [Tübingen 1800]; [2] Allmanach auf das Jahr nach der gnadenreichen Geburt Jesu Christi 1786; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung):

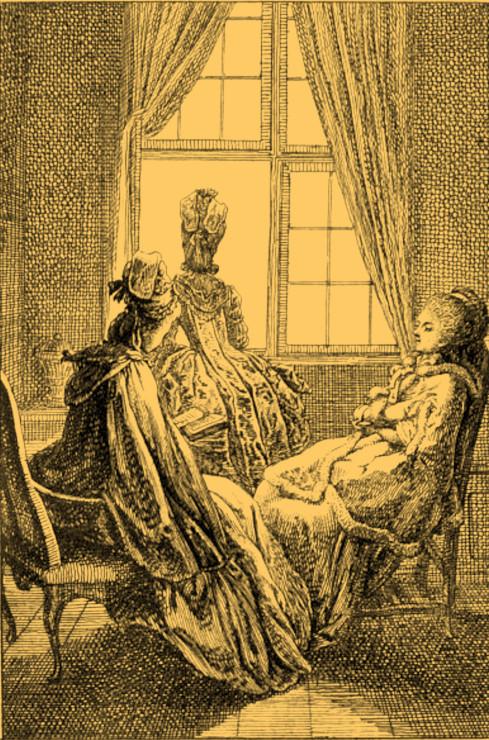

One of Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki’s vignettes in the series Occupations des dames mentioned above, “reading,” features two women reclining in chairs, one of whom is reading aloud, and a third standing and looking out the window; the second vignette features a young woman on a sofa (much as Caroline describes in this present letter) reading Goethe’s Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (Leipzig 1774) ([1] Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Uh 4° 47 [165]; [2] Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur DChodowiecki AB 3.814; third illustration, Lesende Dame, in Chodowiecki, Künstler-Monographien, ed. H. Knackfuss xxi [Bielefeld, Leipzig 1897], 97):

Here an illustration from a slightly later date that also reflects the slight change in fashion after the turn of the century (La belle assemblée or, Bell’s Court and Fashionable Magazine [1808] 5 [July 1–December 31 1808], plate following p. 44):

Translation © 2011 Doug Stott