• 173. Caroline to Luise Gotter: Jena, October/November 1796 [*]

[Jena, October/November 1796]

|404| My dearest Louise, you mean I can send you such a remarkable thing and yet receive no response at all? [1] I refuse to fear anymore |405| that your husband’s indisposition is the cause. Such is probably merely his customary disinclination toward winter, which he will simply have to overcome again. [2] Let me know if I should send you volume 4 of Wilhelm Meister, or have you already read it? [3] There is nothing special in Die Horen.

But the prolific writer Böttiger in Weimar has written a book about Iffland. [4] I would like to send it to your husband for two reasons; first, that he may read it, and, second, that he may tell me if there is anything to it, to wit, if it is an accurate assessment of Iffland; for we already know from the outset what the story is with any book by Böttiger. Schlegel is to publish a rather violent review of the book and yet has not seen Iffland perform. [5] Hufeland would not accept the objection. [6]

So if Gotter might have the time and inclination to write a bit merely about the roles in which he saw him in Weimar, as well as something relating to Böttiger’s assessment, he would be doing his friend Iffland and his most obedient servant Schlegel an enormous favor. Please write me right away and tell me whether he might be willing and whether I ought to go ahead and send the book.

. . . On Saturday Madam Schütz gave a tea party where there was a delicious apple pie, nothing but dainty little women (with one exception), and one highly scandalous bosom. [7] The poor husband had cramps. But she really is a completely shameless creature, and her affected genteelness quickly becomes offensive. [8] Adieu, dear.

Notes

[*] Chronological note: Caroline’s review of August von Kotzebue appeared on 8 November 1796 in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung. Back.

[1] The reference is to Schiller’s Musen-Almanach für das Jahr 1797 with the Xenien; see Caroline’s letters to Luise Gotter on 4 September, 3 October, 15–16 October, and 22 October 1796 (letters 169, 170, 171, 172). Back.

[2] In fact Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter was already gravely ill with consumption and would die on 18 March 1797. Back.

[3] Volume 4, books 7 and 8, of Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre. Ein Roman appeared in October 1796. Back.

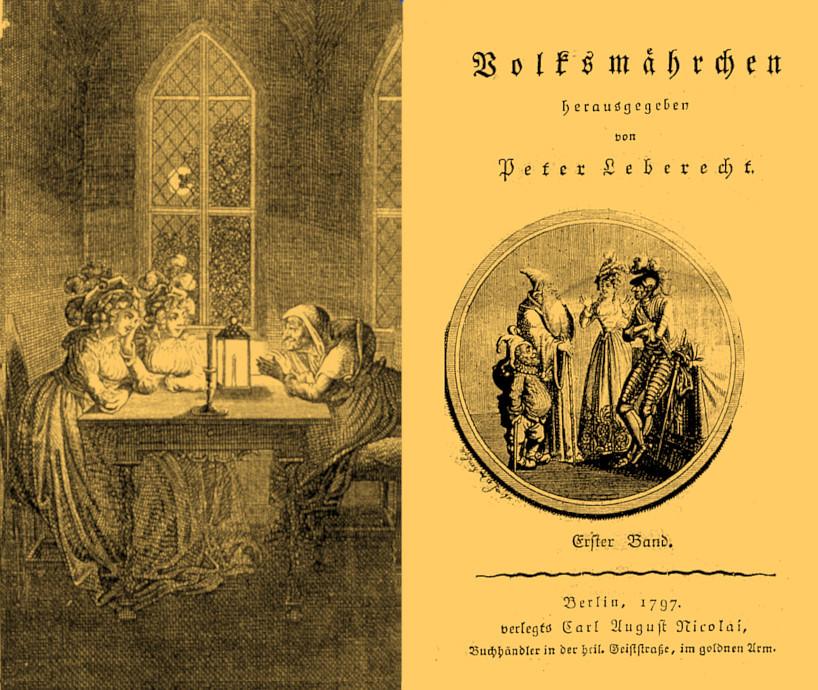

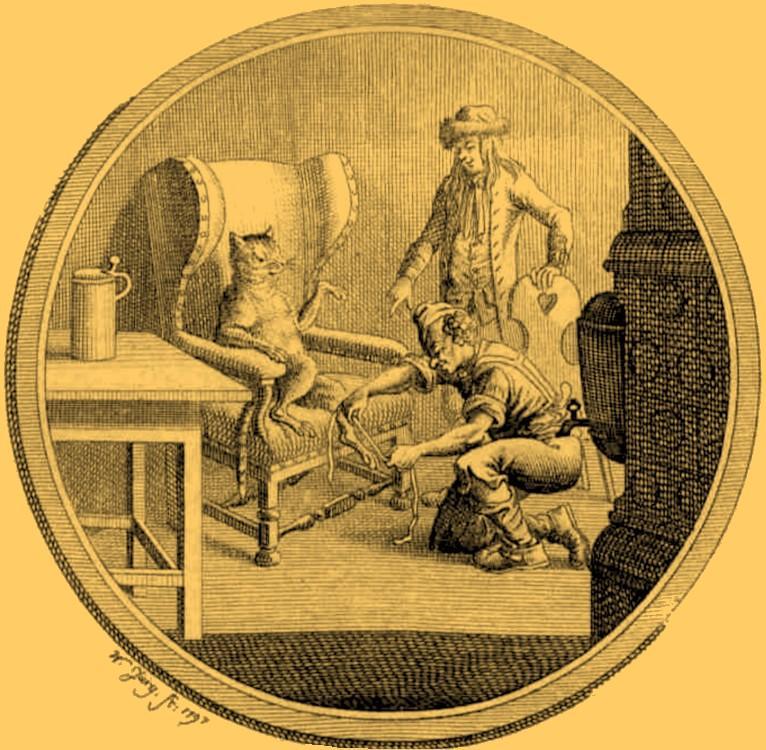

[4] Karl August Böttiger’s Entwickelung des Ifflandischen Spieles in vierzehn Darstellungen auf dem Weimarischen Hoftheater im Aprilmonat 1796 (Leipzig 1796) exhaustively discussed the detailed portraiture style of the guest virtuoso Iffland in Weimar; the book itself was comically taken to task in Ludwig Tieck’s play-within-a-play Der gestiefelte Kater: Ein Kindermärchen in drei Akten mit Zwischenspielen, einem Prologe und Epiloge (the “puss-in-boots” story), in Tieck’s Volksmärchen (Berlin 1797), vol. 1:

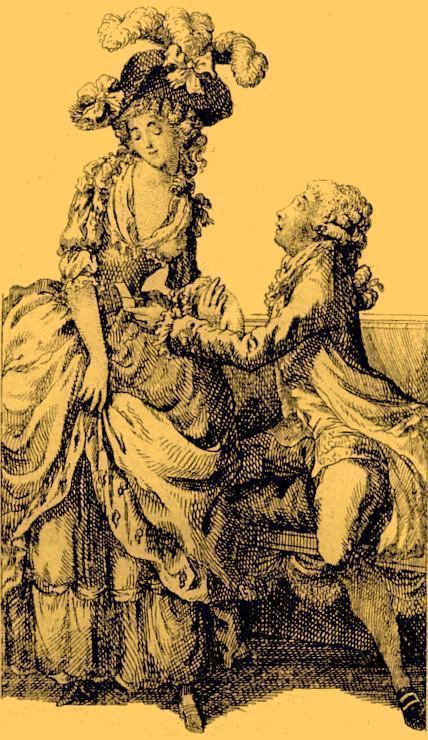

Here the title vignette from the single edition of Der gestiefelte Kater 1797:

Caroline had not yet seen Iffland perform. Back.

[5] For the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung. Although Wilhelm did not publish a review of the book (sending it back to the editors in December 1796 because, indeed, he had not yet seen Iffland perform [Körner (1930), 53]), he did poke fun at it in his Ehrenpforte und Triumphbogen für den Theater-Präsidenten von Kotzebue bei seiner gehofften Rückkehr in’s Vaterland. Mit Musik. Gedruckt zu Anfange des neuen Jahrhunderts (Braunschweig 1801) (Sämmtliche Werke 2:257–342 + 4 pages of musical score; here 2:324, 4th line from the bottom, where Böttiger refers to himself as an “admirer and explicator”). See in general the supplementary appendix on what became known as Wilhelm’s Kotzebuade. Back.

[6] I.e., as one of the editors, along with Christian Gottfried Schütz, of the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung. Back.

[7] Here a social gathering similar to that which Caroline seems to be describing (illustration: Der Freund des schönen Geschlechts: ein angenehm und nützlicher Taschenkalender für das Jahr 1808):

In order in Caroline’s sentence here:

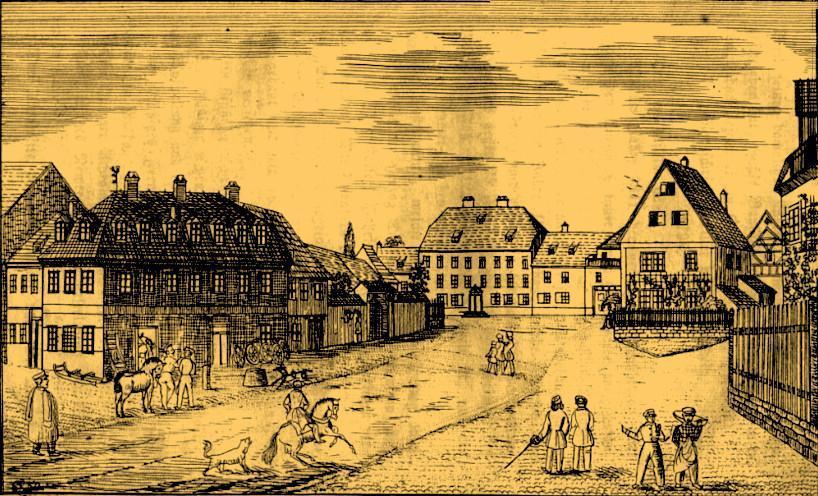

(a) Christian Gottfried Schütz and his wife, Anna Henriette, lived at Engelplatz 8 in Jena until 1804, when they left for Halle (Caroline’s residence at top on Leutragasse; Plan der Residenz- und Universitätsstadt Jena [1884]; Thüringen, Städtische Museen Jena: Stadtmuseum und Kunstsammlung DE-Mb112/lido/obj/12070842; Städtische Museen Jena; ISIL:DE-MUS-873714):

Here an illustration of the Engelplatz looking south, in which case the Schützes’ house would be the one with the fence partially visible at the immediate right (Carl Schreiber and Alexander Färber, Jena von seinem Ursprunge bis zur neuesten Zeit: nach Adrain Beier, Wiedeburg, Spangenberg, Faselius, Zenker u.a.; mit Kupfern Karten. Lithographien u. Holzschnitten [Jena 1850], 197):

(b) Here an illustration of tea being served, from the German translation of Samuel Richardson’s novel Pamela oder die belohnte Tugend, vol. 4 (Leipzig, Liegnitz 1772), plate following p. 326; note the common serving stand for the teapot at right; second illustration: from Iris: Ein Taschenbuch für 1804, Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung:

Here a woman taking her tea, albeit alone, in the mid-eighteenth century with a teapot that looks remarkably modern (Jacques-Philippe Le Bas, Dame prenant son Thé [ca. 1730–55]; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur PFilloeul WB 3.2):

Here two illustrations of tea gatherings, the first from approximately the same period during the mid-eighteenth century but still illustrative of the increasing social acceptance of this drink, about whose health benefits or detriments some still had their doubts, and the second from as slightly later period during the 1820s, illustrating how popular the custom had in the meantime become (in order: M. Blum and G. Spitzel (engraver), Gesellschaft beim Tee, Augsburg mid-eighteenth century; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Signatur GSpitzel AB 2.22; Carl Joseph Haas, Die Familie Vincke [1826: Familie, Tod, Nachkommen, Nachwirkung — Familiengemälde; Privatbesitz Münster, LWL-Medienzentrum für Westfalen/S. Sagurna; no. 79.3.335; cordial communication from Sabine Schierhoff); note esp. the samovar and porcelain service on the table in the second illustration:

There were, of course, more satirical takes on the less genteel side of such tea gatherings, to wit, the danger of their degenerating into gossip and backbiting sessions (“Ein Thé — medisant,” Taschenbuch auf das Jahr 1803: Dem Edeln und Schönen der frohen Laune und der Philosophie des Lebens gewidmet [1804], plate 5; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung):

Wilhelm Schlegel tried to keep abreast of the pros and cons of drinking tea. See esp. his letters to Sophie Bernhardi on 14 and 27 August 1801 (letter letters 327a, 327f): “I hope you have taken to heart my reminders concerning tea”; “Let me implore you no longer to drink as much tea. We have almost done away with it entirely in our household because of its aesthenic effects”; but then on 4 September 1801 (letter 328e): “Tea is now prescribed for you.”

And finally, in 1817, August von Kotzebue included the following lines in his play Der Ruf: Ein dramatisches Lehrgedicht in drei Acten (1817), act 1, scene 8; Hermine, the merchant’s daughter, speaks, while making tea for her company in a kind of samovar (frontispiece to volume; cordial communication from Sabine Schierhoff):

That would be my drink of choice were I to write a novel, For what fine similarity we find between tea and love! . . . First, those who are lucky Pick both at the most favorable of times: To wit: when both are yet young. For a tea leaf can be rolled just like a rose petal, Providing a savory fragrance, drawn from each when young. And then: both love and tea are preserved in the ardor of passion, Which, when too quickly heated, may devour many a comely leaf. Finally, much that is bitter must be sweetened in both love and tea, One cannot enjoy either without cream and sugar. A woman's gentle temperament provides the sugar —

(c) Here one sample recipe from countless candidates for apple pie or pastry (Caroline spells it Aepfelkuchen) at this time, albeit from a popular cookbook published in the year Caroline is here writing, 1796, that enjoyed numerous editions well into the late nineteenth century, namely, S[ophie] J[uliane] W[eiler] (1745–1810), Augsburgisches Kochbuch, 5th ed. (Augsburg 1796), 489–90 (title vignette to volume):

Line a bowl with thin butter pastry. Cut apples into small chunks according to taste, sprinkle the bottom of the bowl with ground sugar [from a sugar cone] and cinnamon, place apples on top; sprinkle on another layer of sugar and cinnamon with small slivers of butter; then yet another layer of apples, and another layer of sugar and cinnamon. Beat together sweet cream with eggs according to taste, pour the batter onto the mixture, and bake.

(d) “With one exception”: namely, Caroline herself.

(e) One cannot know, of course, which fashion prompted Caroline to view a bosom as “scandalous” (she uses the French cognate skandaleus, for scandaleux) or even whether she is referring specifically to Madam Schütz, concerning whose reputation, however, see the next footnote.

The following discussion is based on cordial communication from fashion historian Sabine Schierhoff: Madam Schütz, at the time about forty-five years old, was in any case no longer really the target age of fashion illustrations in magazines such as the Journal des Luxus und der Moden, which frequently addressed younger women. At the same time, however, she was likely not entirely alone in her wish — if such be attributed to her in this case — to follow fashion trends more concurrently than a “step behind” or with a “more concealed” bosom as suggested by the following author.

To wit, in January of 1796, an anonymous author published an essay in the Journal des Luxus und der Moden concerning the differences between current fashion choices for younger and older women (anonymous letter, “Frankfurt a. M., 16 December 1795,” Journal des Luxus und der Moden 11 [1796] 1 [January], 57–59; copper engravings p. 64a, fig. 1 and 2). Although the author points out that in Frankfurt am Main, unlike other towns perhaps, especially concerning women between 28 and 48 years of age and despite indistinct transitions from case to case, women of middle and more advanced age did not dress essentially any differently than younger women, wearing short-waisted chemises, small hats, flat shoes, cloaks, and larger shawls — in a word: quite the wardrobe of younger women.

That said, he acknowledges that fashion customs might indeed apply differently to women of different ages, making it possible to discern a certain character and conventional type of wardrobe among older or more mature ladies who exhibit both intelligence and good taste in their clothing choices. He enumerates several points that such women might keep in mind when choosing a wardrobe:

(1) Choose gentler, more modest, and more muted colors for clothing and ribbons rather than bright, lively, ostentatious ones;

(2) Do not wear flowers or feathers as head covering;

(3) Wear more modest but deep bonnets and head coverings rather than romantic, wild hairstyles or affectedly youthful head adornment;

(4) Keep one’s bosom less exposed, that is, more concealed than earlier, and enclosed with a scarf;

(5) Wear more cloaks, shawls, and wraps than is the custom among younger women; and in general, with respect to the primary categories of clothing, e.g., Angloises, chemises, Polonaises, foureaus [form-fitting dresses], bonnets and hats: continue to follow the regnant or current fashion, but do so somewhat belatedly, that is, always one step behind, simultaneously avoiding any and all exaggeration.

The author provides two drawings illustrating the current fashion (1796, when Caroline is here writing) as worn by, first, a young woman, and, second, a more mature woman. The younger woman is wearing, among other things, a

so-called Greek chemise with a small collar and a scarf hanging at an angle from the right shoulder down to the left hip and fastened beneath the woman’s belt. The gold-embroidered belt is gathered along the sides and fastened with a golden cord at the front. This chemise sits on the young women quite well, and lends to both the head-covering and the woman’s overall figure a cheerful, youthful appearance.

Although the fashion sensibility of the Weimar Journal des Luxus und der Moden was sooner of the more modest sort than in, say, the French Journal des dames et des modes, nonetheless the current trend of imitating certain fashion elements from classical antiquity was indeed beginning to surface in German fashion journals as well, e.g., the German edition Journal des Dames et des Modes published in Frankfurt, which published the following illustrations of the current costume parisienne in 1797 with a more exposed (if perhaps not yet scandalous) bosom:

Compare by contrast the illustration from the February 1797 issue of the more modest Journal des Luxus und der Moden, an illustration in and of itself representing the boldest such exposed bosom of that year’s issues:

As early as the late 1780s and early 1790s, the French portraitist Louise-Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1755–1842) began painting portraits in this style imitating antiquity, that is, with delicate, flowing, lightly draped fabrics that represented a departure from the more restrictive fashion of the 1780s, especially as the latter used stiffened stays, which over the course of the 1790s were replaced by short stays.

This change yielded a more flowing, softer silhouette, and light cotton fabrics became increasingly popular for such clothing. Fashion magazines then introduced the middle class to these changes, and at least certain elements of fashion became dictated less by the aristocracy or court, as was earlier the case, than by the sensibility and taste of the middle class.

These changes into lighter and more flowing forms had already begun, if slowly, in 1795, and Caroline may well be picking up on the manifestation of these changes, including the more exposed bosom, even in social gatherings in tiny Jena, presented either by Madam Schütz herself or by one of the other ladies present.

Concerning this fashion trend and Caroline’s tongue-in-cheek remark, see finally the similarly tongue-in-cheek poem “On the Fashion of Bare Bosoms” that appeared shortly thereafter (1801) in the Journal des Luxus und der Moden, a poem echoing the gentle levity of Caroline’s remark in this letter (“On the Fashion of Bare Bosoms,” part of “Poetisches Bonbon fürs Mode-Journal,” Journal des Luxus und der Moden 16 [1801], June, 285–88 here 286–87; approximate prose rendering; the allusion is to the motif as executed in the late fifteenth-century painting Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli or elsewhere):

On the Fashion of Bare Bosoms

When by fashion compell'd, Amoene dear, yet bashful still, The delicate, diminutive, bosom does display But half its comely pair to our eyes: Dearer not is e'en Venus herself, When from the ocean's silver spray She does so virginally arise.

Yet when she who is so portly and plump (You know her name) her bosom o'er-amply endowed So blatanly exposes to the unsuspecting crowd: Then tell me true, is't not as if Venus indeed From the ocean's spray does still emerge, But quite backwards now, showing first her rump? Back.

[8] Garlieb Merkel publicly opined that “although he [Christian Gottfried Schütz] was allegedly not happy in his family life, the assertion — supported by proofs adduced to the contrary — was made that he was in fact not being deceived, but rather merely derisively overlooking what he could not prevent.”

To wit, Jean Paul writes to his friend Christian Otto from Weimar on 23 August 1798 (Jean Paul’s Briefwechsel mit seiner Frau and Christian Otto, ed. Paul Nerrlich [Berlin 1902], 74):

I went to visit Schütz yesterday (Schiller reported being sick), accompanying him then to the Wednesday Assembly. I took a long and circuitous walk with his wife, who is to be reckoned among the most base coquettes, those for whom the most appropriate response is simply to banter playfully with them.

In the gentle evening air she accompanied the author of Hesperus [i.e., Jean Paul himself; Hesperus oder 45 Hundsposttage, eine Biographie (Berlin 1795)] to the top of the most beautiful height (that she, too, might be lofty); although her face is indeed beautiful, her most beautiful feature is her Cleopatra’s eyes, prompting me to keep repeating to her: “I do not believe a word you say unless you are looking directly at me.”

Achim von Arnim, Armuth, Reichthum, Schuld und Busse der Gräfin Dolores. Eine wahre Geschichte zur lehrreichen Unterhaltung armer Fräulein, 2 vols. (Berlin 1809), apparently caricatures her as Niobe, the professor’s wife.

The passage occurs in vol. 1, section 2 of the novel, “Reichtum” (Wealth), chapter 10, “Stories from the Life of Pastor Frank.” Pastor Frank relates how early in his life his mother had an inordinate, almost obsessive fear of him being seduced, though, he remarks, “I am still not quite clear just what I understood by the word ‘seduce.'”

She eventually accompanied him to the university, even to his lectures, waiting for him to come out again. She ceased only after it became clear he would otherwise end up having to fight those who were mocking him. The narrator picks up the story:

In the meantime, since it seemed that some liaison or other with a woman was yet necessary for my education, I decided to try my luck with the wife of a certain professor, she being the only respected woman of my acquaintance in the town and rumored to be frivolous. . . .

I timidly used this situation of complete darkness [during the presentation of a “magic lantern”], where my own embarrassment would not be evident, to whisper sweet nothings to her, gently placing my hand in hers, which she then held tightly; I was absolutely certain I was about to gain an easy victory here. And please consider for yourself whether my conclusion was so off the mark, since among the eight children this Niobe was rearing to be both beautiful and strong through a carefully considered plan of physical upbringing, three were attributed to other fathers.

The husband himself did not contest this situation, maintaining that before his own praxis had grown to its present size he was indeed able to devote himself to his wife, whereas now he was constrained to sacrifice his own happiness to a broader sphere of activity and grant his wife her freedom.

I visited her the next day; again she cordially squeezed my hand, and I again began to speak tenderly with her. Halfway through, she already knew what I wanted, told me so, and yet assured me that, as fond as she was of me — for she insisted she had grown as fond of me as of her own son — that was one favor she could not do for me.

[Goettinger Taschen Calender vom Jahr 1789; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung:]

She explained to me that her love belonged only to the most distinguished, cultivated mind; for just as she herself was able to give her children excellent health, so also should they receive the most complete intellect from their father. Whereupon she named the fathers of her three youngest children, and I was astonished to hear the names of three distinguished men, some whose acquaintance she had traveled great distances to make. She swore that though none among them was as handsome or charming as I, her entire soul had clung to them, and that I for my part should first distinguish myself in the exercise of some splendid talent or other. Then, she said, I should return to her, and she would fall at my feet.

This utterly straightforward confession relieved all the embarrassment oppressing me, and in taming one part of my curiosity, it awakened yet another, namely, to learn more from this unique woman who was carrying around with her a completely developed system of metaphysics void of all literary pretension. “Every chorus,” she continued,

left to itself, imperceptibly begins to sing at a lower pitch; mere impulse, physical inclination thus inclines toward the inferior; without a higher disposition, entire nations can stupefy, and wars are thus necessary for such nations because it is only under duress that most people come to view talent as truly grand and worthy. I myself have a natural reverence for intellectual magnificence, so much so that I quite naturally, without coercion, surrender myself to such talents; indeed, it is precisely because of his comprehensive intellect and mind that I chose my husband.

I swear to you, it is solely the fault of the mother herself who brings healthy stupes into the world from the usual race, stupes born utterly without any higher sense and who even in the most ordinary circumstances of daily life flee before every divine nature. She no doubt allowed herself to be deceived by some unworthy man, calling “love” what was in fact merely animal instinct within her.

Love is a terribly abused expression. Love is wholly intellectual, spiritual, and involves the most profound humility before another nature. Its organ is sensuality, nothing more.

And now ask yourself whether you — who have developed absolutely no unique character of your own, who are still preening yourself with sham knowledge and clothes, who still do not even know what you want and are not yet driven by any real element of enthusiasm — whether you really had the right to make declarations of love to a woman like me. I have heroically endured eight childbeds, which is the same as enduring eight major battles; at least that is how I approach it, namely, with the disposition of a hero: I hear the trumpets, the battle is difficult and painful, but is also the highest thing I can accomplish.

But just as wars are not there merely for the sake of war, so also birth not merely for the sake of birth, or so that the same issues from the same — for in that case our lives would be unworthy — but so that something higher be attained. Young man, if you feel something of this in yourself, merely despising the age will not help; you must first come to understand this age. Truly, my own children will far, far surpass me.

After these words, she got up, kissed me as if wanting to lay me on her breast, and said, “I must to my dairy; I have to nurse my child.”

[Goettinger Taschen Calender vom Jahr 1787; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung:]

Translation © 2012 Doug Stott