• 57. Caroline to Luise Gotter in Gotha: Clausthal, 22 June 1785 [*]

Clausthal, 22 June [17]85

|116| Your husband is a false prophet, my dear Louise, and your own wonderful example seduced me into entertaining false hopes. You are well aware, my dear, how happy the successful birth of your little Gustav and the opportunity to be a godparent made me; but even before the all-important hour itself arrived, a dark shadow was cast on this cheerful prospect by the unexpected death of two daughters of our friends, the Dahmes, one of whom was my favorite. [1]

Closed up in my room here for two full weeks against the foul weather and the fear of contagion, I experienced in anticipation not only certainly all the joys, but also all the afflictions of motherhood [1a] — until at last the day came that would make me, too, a mother, albeit amid a thousand prolonged sufferings and fearful anxiety. The final moments strained my powers to the limit, for I feared the baby was already dead [2] — this notion and the sight of the final, broken rays of the sun falling on the bed opposite me, as if to consecrate it for tears —

O, it was high time to put a stop to such notions. And then there was an all-too-brief moment of joyous exhilaration that spread throughout the entire house — my husband, beside himself now that the lives of his wife and child had been saved, poor Lotte, whom I had not even seen for several days, kneeling next to my bed, her heart full of bliss — and I, enjoying it all. [2a]

I fell into a slumber from which I awoke barely conscious, followed by 14 horrific days and nights spent in a violent nervous fever during which, despite an overwhelming urge to sleep, I could not even close my eyes without being immediately roused by convulsions and frightful hallucinations; a time when Böhmer often feared for my very life |117| and I for my own mind, of whose confused state I was most sadly aware; [3] when I everywhere saw only sadness, when even my precious child did not gladden me apart from the gloomy satisfaction I took, leaning over it, in being able to weep! So weak was I in body and soul that I shrank equally from both rest and activity. —

But it is over, and I thank God for having rescued me through the enormous efforts of my husband, for whom my respect and tenderness have doubled as a result of the countless demonstrations of his own during this episode and as a result of the steadfastness from which he never wavered, not even during the most acute danger. I have recovered only very slowly, and it has only been during the past few days that I have once again felt completely healthy. During this time my parents came for a visit, [4] as did the young Meyers on their way to Hamburg. [5]

There has certainly been no lack of physicians of all sorts for this poor sick woman, and if love could heal, I would surely have been able to get up and walk about again as if moved by a miracle. “Gustav” turned into an “Auguste,” and this charming creature silently requests through her goodness and beauty that everyone be satisfied with her after all; and as far as I am concerned, I would much prefer a daughter — for whom a mother’s heart doubtless beats more sympathetically and with whom I can certainly begin having a relationship much earlier. And the father? — ah, he was only too happy to forget the original choice! [6]

Although I was still very ill when I received your letter, my dear Louise, it certainly did not fail to achieve its amiable goal, and I was exceedingly pleased with its entire content. May heaven repay you through your other children the suffering it brought you in Pauline, and may it allow this poor little one to pass on to a sweet peace soon. [7] The feeling of loss is, after all, less painful |118| once one has reached the point where the loss itself comes as a blessed relief, and our memory is less bitter than if our heart’s precious one passes away in the full blossom of health, amid the most charming enjoyments of life. How painful, wrenching is the feeling then when we have to ask providence — Why? How grudgingly, reluctantly does the image of death then join our memories of the living person. [7a]

You have been guided step by step to the point of surrender — it will not be hard for you now — the gaze with which you [turn] your eyes toward providence can only reveal gratitude for the grief you have successfully endured. Parting is difficult when the loveliest of hopes still fill and inspire our soul; but once those hopes have been borne to the grave — should we really weep more than a single melancholy tear over the tombstone?

Could I but bring Auguste together with my little godchild. Although my good brother has suggested I plan a trip to Gotha at Michaelmas, I cannot even consider it, since, even as it is, I will soon be leaving Böhmer for several weeks while I am in Göttingen. My mother-in-law is once again spending some time at a mineral springs spa near here, [8] and I will be accompanying her there [to Göttingen]; I am really looking forward to it, and they in their own turn are looking forward to seeing me and my child.

Along the way, which passes by Catlenburg — thus the name of the fairy castle of Bailiff Reinbold — I am hoping to see Madam Sturz. [9] Until then I will also be taking several excursions to Gittelde [10] to see Madam Böhmer, Louise B., and the Hofrath.

The summer, which has arrived so slowly, will pass quickly amid many such distractions. Its end will be accompanied by a separation that I hardly dare even mention. [11]

Fate has some extraordinary things in the works for Therese — the foundation for them resides in Therese herself. God grant that they take a turn for the good! [12]

|119| I also was still rather weak-minded, my good Louise, when I read the finished end rhymes; nonetheless not for a moment would I have claimed to be able to decide who was the author of this and who of that. The heavenly figure of the beloved could not be mistaken in the mouth of the one, and the rather satirical face not in the eye of the other. Might the duchess have appeared quite graciously inclined upon receiving the latter? [13]

I must take my leave from you now, my dearest friend. As soon as I can, I will be with you again. In the meantime, please do not forget your Caroline.

Notes

[*] Extracts from this translation appear in Deborah Simonton, ed., Women in European Culture and Society from 1700: A Sourcebook (London: Routledge, 2014), under the rubrics “Women’s identity in Eighteenth-Century Culture,” chapter 1: “Intimate Lives: Self, Sex and Family,” “Mothers and Mothering.” Back.

[1] These two daughters are otherwise unidentified. Georg Christoph Dahme had twelve children, six of whom survived him. In his eulogy for Dahme in Nekrolog der Teutschen für das neunzehnte Jahrhundert, vol. 2 (Gotha 1803), 224, Friedrich Schlichtegroll mentions how the death of a “beloved daughter and son . . . in the blossom of life” toward the end of Dahme’s life greatly depressed him. Back.

[1a] Raphael Steidele, Abhandlung von der Geburtshülfe, vol. 1: Verhaltensregeln für Schwangere, Gebährende und Kindbetterinnen (Vienna 1803), 73:

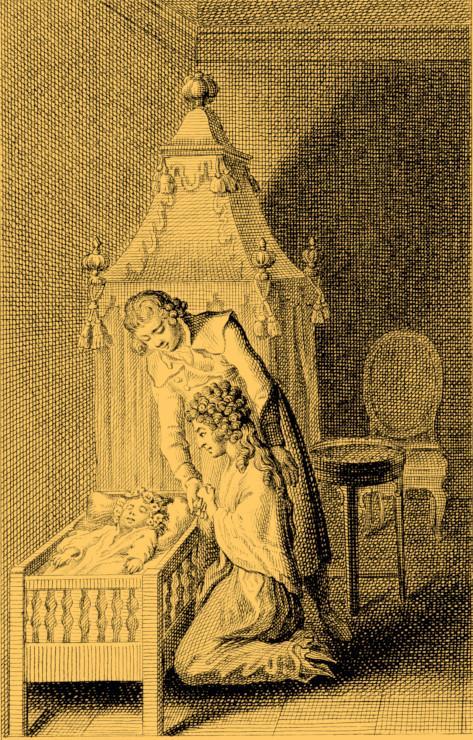

[2] Caroline is not being overly dramatic. Childbed and confinement were never entirely predictable or straightforward affairs during this period, and the period immediately before birth least of all. Here a contemporary engraving by Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki portraying this uncertain time for the pregnant woman at home (Kupfersammlung zu J[ohann] B[ernhard] Basedows Elementarwerke für die Jugend und ihre Freunde: Erste Lieferung in 53 Tafeln. Zweyte Lieferung in 47 Tafeln von L bis XCVI [Leipzig, Dessau, Berlin 1774], plate 29a):

After a child was born, its health in these early days of modern medicine was still constantly at risk. Caroline herself lost two sons in infancy (Johann Franz Wilhelm and Wilhelm Julius), a daughter two and a half years old (see Caroline’s account in her letter to Philipp Michaelis in December 1789 [letter 97]), and then Auguste at fifteen years of age. See below concerning the death of Luise Gotter’s own child.

Here two trenchant illustrations of the threat of infant death by Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki. In the first, a mother tries to ward off death while nursing; in the second, death snatches a child while the dry-nurse, unaware of what has just happened, continues to rock the empty cradle (Die Mutter [1791]; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur DChodowiecki AB 3.889; Das Kind [1791] Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur DChodowiecki AB 3.898):

Here the grieving parents and the deceased infant (Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki and Daniel Berger, Nehm er ihm hin der uns ihn gab [1790]; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur DBerger WB 3.4; Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, Totes Kind [1774–75]; Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Chodowiecki Sammlung [1-56]):

In the following illustration of a double tragedy, Sebaldus Nothanker and his daughter Marianne wait and watch at the bedside of Madam Nothanker, who is dying, and next to the Nothanker’s child Charlotte in the coffin (Sebaldus am Sterbebette [1774]; Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Chodowiecki Sammlung [1-52]):

[2a] Similar scenes (Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, Erlauben Sie mir Ihnen vor zu beten [1776]; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur DChodowiecki AB 3.159; second illustration: Frauenzimmer Almanach zum Nutzen u Vergnügen für das Jahr 1799):

[3] Illustrations by Daniel Chodowiecki (Nein, mein Freund ich fühle mich; der Tod dringt auf mich ein; wir müssen uns verlassen [ca. 1782–97]; Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Uh 4° 47 [263], from a novel by Rousseau; Gott, du hörst es, ich will ihr gern mein Glück aufopfern [ca. 1787–95]; Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Uh 4° 47 [265]):

Concerning the related context of confinement, see Caroline’s undated letter to Lotte Michaelis in 1785 (letter 53), note 2. Concerning the perils of childbirth for the mother, see esp. Caroline’s account of the tragic episode with her sister-in-law in her letter to Wilhelm Schlegel on 26–27 March 1801 (letter 303), esp. with additional cross references, including to the equally tragic episode with Lotte Michaelis, in note 6 there. Back.

[4] Johann David and Luise Philippine Antoinette Michaelis. Back.

[5] Friedrich Johann Lorenz Meyer and his new wife, Friederike, née Böhmer, who had just married on 12 April 1785.

Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki did a series of vignettes in 1780 with the title Occupations des dames; one of those vignettes, “Visits,” features two women visiting a third in childbed with her newborn infant; second illustration, Die Wochenstube, from Chodowiecki, Künstler-Monographien, ed. H. Knackfuss xxi [Bielefeld, Leipzig 1897], 16; third illustration: color variation of the first above, Die Wochenstube (painting) (1770):

Another vignette by Chodowiecki similarly portrays the visits of family and friends to the mother and child during the period immediately after birth, and a final vignette by S. Halle offers a similar presentation of the newborn infant to family, friends, and domestics (Kupfersammlung zu J[ohann] B[ernhard] Basedows Elementarwerke für die Jugend und ihre Freunde: Erste Lieferung in 53 Tafeln. Zweyte Lieferung in 47 Tafeln von L bis XCVI, plate 29b; S. Halle, Präsentation des Neugeborenen [ca. 1751–1800]; Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Graph. A1:938):

[6] Caroline and her husband had originally anticipated a son, whom they were planning to name Gustav; see Caroline to Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter on 7 April 1785 (letter 55) (Frauenzimmer Almanach zum Nutzen u. Vergnügen für das Jahr 1798; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung):

[7] Sickly little Pauline Gotter died on 15 August 1785; the Gotters’ daughter by the same name, born 29 December 1786, appears later in these letters. See Caroline to Luise Gotter on 1 September 1785 (letter 60). See also Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter’s poem “Pauline,” in his Gedichte, vol. 1 (Gotha 1787), 214–15 (illustration: .

Pauline 1785

Inexpressible paternal joy, Inexpressible paternal grief, Precious firstborn! But no, my breast I shall not wildly rend at your irreplaceable loss, Nor, with hair torn asunder, Lose myself in an ocean of tears. Instead would I your brief life recollect, Exemplar of acquiescence to God. And, should e'er false fortune's light Again my eyes blind, so upon your grave shall I gaze: Here, in the bud yet unopened, Did descend my bliss, and my pride. Back.

[7a] Such was precisely the situation in which Caroline found herself when she lost Therese and then especially Auguste. Back.

[8] Unclear reference. Back.

[9] Katlenburg (also Catlenburg; Caroline also spells it Catelnburg) in Lower Saxony, ca. 22 km southeast of Clausthal (past Osterode), 20 km northeast of Göttingen; here Katlenb[ur]g-Duhm) (Karte des deutschen Reichs, ed. C. Vogel [Gotha 1907], no. 13):

The chateau from which the locale derives its name is a former fortress and monastery complex built in the eleventh century as an elevated fortress protected on two sides by 50m cliffs and on two sides by the Rhume River; the swampy surrounding area made ingress difficult for advancing enemies (photo courtesy of Birgit and Kristian Schlegel, Katlenburg):

The monastery in the complex was secularized in 1534 after the Reformation. In the late sixteenth century Philipp II of Grubenhagen resided in the complex with his wife, Clara von Wolfenbüttel, changing part of the early monastery complex into a Renaissance castle, where they lived until 1595, after which a bailiff (Germ Amtmann) resided there, functioning as administrator, adjudicator, and manager of the complex.

One important consideration when assessing Caroline’s references to the locale involve the names themselves. Because at the time everything on the elevation was called “Catlenburg” and was part of the administrative complex there, and everything in the village below was called “Duhm” (from 1865 Katlenburg-Duhm, from 1974 Katlenburg), Caroline is referring to the administrative complex on the elevation, not the village. Hence she was apparently quite familiar with both the complex itself and the current official, Senior Bailiff Johann Arnold Reinbold, her mother’s maternal uncle, who held the position from 1785 till he died on 5 January 1793; that she refers to him by last name only suggests Luise Gotter was already acquainted with the name as well.

When Caroline passes by the same estate in April 1795 on her way from Gotha to Braunschweig, she mentions the windows of a “very familiar house” (to Luise Gotter on 16 April 1795 [letter 149) (see in general Katlenburg und Duhm. Von der Frühzeit bis in die Gegenwart, ed. Birgit Schlegel [Duderstadt 2004]; also Birgit Schlegel, “Caroline und das Feenschloss,” Südniedersachsen: Zeitschrift für Regionale Forschung und Heimatpflege, vol. 39, no. 1: March 2011, 4–7) (thanks to Birgit and Christian Schlegel for photos and historical information). Back.

[10] Gittelde is a small village located 10 km due east of Clausthal (K. Baedeker, Northern Germany as Far as the Bavarian and Austrian Frontiers, 11th ed. [Leipsic 1893], map following 378):

Here in engravings ca. 1650 (Vaterländische Geschichten und Denkwürdigkeiten der Vorzeit . . . Braunschweig und Hannover, 2nd ed. Wilhelm Görges [Braunschweig 1881], 275) and by Matthäus Merian ca. 1658:

It is unclear what Madam Böhmer was doing there. Back.

[11] Is Caroline referring to her and Auguste’s arrival back in Clausthal at the end of August after her first visit back to Göttingen since her marriage? See Caroline’s letter to Lotte Michaelis on 25 August 1785 (letter 59). Back.

[12] Therese Heyne had become engaged to Georg Forster on 18 April 1784 and would be marrying him only a couple of months after Caroline’s letter here, on 4 September 1785. Back.

[13] Bouts-rimés (or bouts-rimez), “rhymed ends”, a kind of poetic game defined by Joseph Addison, in the The Spectator 60 (Wednesday, 9 May 1711), 7–8, as

a List of Words that rhyme to one another, drawn up by another Hand, and given to a Poet, who was to make a Poem to the Rhymes in the same Order that they were placed upon the List: The more uncommon the Rhymes were, the more extraordinary was the Genius of the Poet that could accommodate his Verses to them.

That is, the more odd and perplexing the rhymes, the more ingenuity is required to give a semblance of coherency to the poem. See Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter, “Liebeserklärung in vorgeschriebenen Endreimen,” Gedichte, vol. 1 (Gotha 1787), 297–99; concerning the “duchess” Caroline mentions, see the subtitle glossed in a footnote to Gotter’s piece: “The following piece was prompted by the capricious whim of a charming princess to test the author’s imagination by selecting the most Baroque rhymes along with several expressions not found even in poetic dictionaries”:

Declaration of Love in Prescribed End Rhymes 1785

Thee I love more than was Hannchen by Christel, Though snow-cold the bosom that nigh bursts its Nistel [lace] And deaf your heart be as an unfeeling Distel [thistle]. Early and late do I sing bass and Fistel [falsetto]; Write e'en in my dreams, the most pathetic epistle. From grief does my heart wilt as does the stale Mispel [medlar]. My body a shadow, my voice but Gelispel [whisper]. When in my head will repose the loud Haspel [bobbin or winch]? When death release this pris'ner from the Raspel [rasp]? Pray bring to an end, O Lachesis, your Zaspel [thread-bobbin]! (But sense and rhyme flee, the word now being Bastel [handicraft].) Ah, might I but serve as your night-table Schachtel [box]! I dwell in the cage there instead of your Wachtel [quail]! Ah, but for a kiss (and be the payment a Dachtel [slap]) Would I gladly pay with my life's entire Achtel [eighth portion]! Back.

Translation © 2011 Doug Stott