Munich

Munich from a distance, where Caroline and Schelling moved during the autumn of 1806 and where she would find her final residence.

(Eduard Duller, Die Donauländer nebst Wanderungen etc., 3rd ed. [Leipzig 1847], plate following p. 80.)

Munich, Western City Gate, 1826

On moving to Munich in May 1806, Caroline and Schelling initially lived in this relatively new complex of buildings constituting the western edge of the original city walls with the address Karlsthor 7. They lived in the wing to the right, on the third floor in the next-to-last house on the right, no. 7 (house numbers read from left to right in that ensemble; the corner house was no. 3). The scientist Johann Wilhelm Ritter, their acquaintance from Jena, also lived in this complex of buildings.

(Painting by Franz Thurn [1826].)

Uniform Embroidery for the Bavarian Academy

Schelling, much to Caroline’s pride and delight, was appointed a member of two different societies in Munich: first to the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities (27 July 1807), then to the Academy of Fine Arts (13 May 1808), of which he was also general secretary.

A local governmental publication summarizes the uniform of the members of the Academy of Sciences and Humanities:

“According to the pertinent prescript issued on 19 June 1807, this uniform consists in a garment of dark blue cloth with a crimson silken collar and a rich gold embroidery of intertwined oak leaves and laurel branches; the state garment for all members consistently has this embroidery; the small uniform has it on the collar, facings, and pocket flaps; the dress coat only on the collar. The clothes worn underneath are of white cloth. See the Regierungsblatt (1807) 32, where illustrations of the embroidery can also be found.”

(Illustration: “Die Uniformirung der akademischen Mitglieder betreffend,” Königlich Baierischen Regierungsblatt [1807] 32 [1 August 1807], 1226–31, with embroidery illustrations following p. 1233; text: Denkschriften der königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu München für das Jahr 1808 [Munich 1809], xvi.)

Sophie Bernhardi, née Tieck

Caroline writes on 31 January 1807:

“Madame Bernhardi the Insufferable remained behind there [Rome] with the sculptor Tieck. Knorring will also be returning . . . perhaps there will even be a divorce from Herr Bernhardi, since Knorring is utterly in the clutches of this pale, gaunt, toothless and eyebrowless and hairless woman with her imperious, obstinate, essentially evil character—but Tieckean visions.”

It may be recalled that Wilhelm Schlegel had had an intense affair with Sophie Bernhardi when he lived in Berlin but was still married to Caroline. In any event, Sophie Bernhardi would indeed end up in Munich while Caroline was there.

(Portrait by an unknown artist [ca. 1825], when her last name was in fact von Knorring rather than Bernhardi.)

Madame de Staël

During 15–21 December 1807, Wilhelm Schlegel and Madame de Staël were in Munich on their way to Vienna; Caroline and Schelling dined with them one evening.

During the autumn of 1808, Friedrich Tieck was Madame de Staël’s guest in Coppet, where he did this bust of her. Caroline writes on 23 November 1808 that Tieck “is just now occupied in Coppet with turning Madame de Staël into — well, into a bust.”

(Bust by Friedrich Tieck [1808].)

Caroline’s Final Residence

The last apartment in which Caroline lived, essentially as it looked when she and Schelling were living there. It was located in Munich at the address Im Rosenthal 144 (the later house number 15 was added here later by an unknown hand). She and Schelling moved into this building during the autumn of 1808 (Caroline was already familiar with the apartment in September of that year) and seem to have occupied the third story.

(Münchner Polizey-Uebersicht [1805] xxv and xxvi [Saturday, 25 June 1805], plate xxv.)

Karl Friedrich von Rumohr

A close and entertaining but erratic friend of the Schellings in Munich who shared their enthusiasm for art.

“Our barone,” as Caroline refers to him, was an art historian who published a multivolume, pioneering work on Italian art as well as a book on cooking that is still in print today. Caroline writes in 1808:

“His sense for hearty eating is equally well developed. There can be absolutely no criticism of his understanding of cuisine, except that it is abominable to hear someone speak as intimately about a lobster as about a portrayal of the little Lord Jesus.”

(Portrait: oil by F. C. Gröger [1802].)

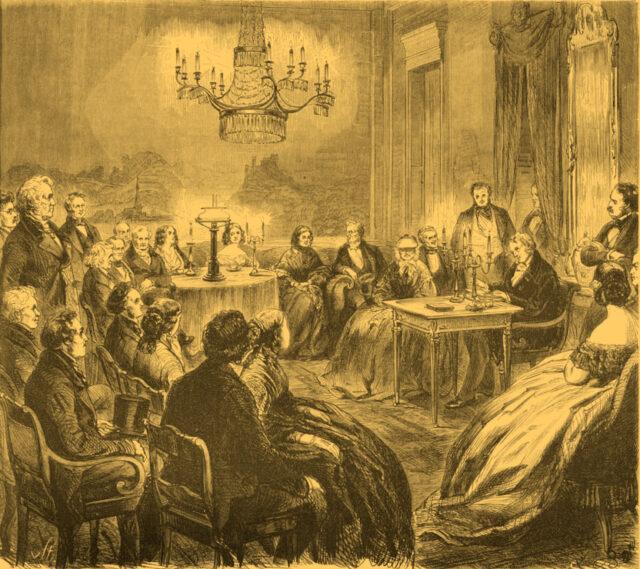

Dramatic Reading by Ludwig Tieck

Ludwig Tieck, who had arrived in Munich with his sister, Sophie Bernhardi, in October 1808, had often done similar dramatic readings back when the Romantic circle had been gathered in Jena. Here an illustration of such an evening with Tieck, seated at the table on the right, reading before friends after he moved from Dresden to Berlin in 1840 (Schelling is seated at far left).

Caroline writes on 23 November 1808:

“Tieck, who reads plays aloud and who on several evenings has already transported us into that illusion where one feels one is sitting before a stage on which every role has been assigned to the most select actor. Although he was already excellent at reading aloud earlier, now it is the best one can experience in that genre, indeed, it is something quite singular. He virtually shapes each piece precisely by reading it as he does.”

(Ludwig Pietsch, “Ein Abend bei Ludwig Tieck,” Der Bazar. Illustrirte Damen-Zeitung [1866] 42 [8 November 1866], 337–38, illustration on p. 337.)

Bettina Brentano

Bettina Brentano writes from Munich on 6 November 1808:

“Yesterday when I visited them [Ludwig Tieck and Sophie Bernhardi], I found Madam Schelling already there, as ugly as a worn-out fur wrap. She invited me to come visit her that evening with Madam Bernhardi, but since her husband is no less handsome than she herself, I thought that such a feast for the eyes would be a bit too opulent for my own, and that my eyes might well overeat having to gaze upon these countenances during an entire evening.”

Caroline:

“Then also Bettina Brentano, who looks like a little Berlin Jewess and racks her brain for wit, not that she is by any means wanting in intelligence, tout au contraire, but it is so sad to see how she strains, distends, and distorts that which she has. All the Brentanos have an extremely unnatural nature.”

(Portrait: unknown artist [ca. 1810]; citation: Schelling im Spiegel seiner Zeitgenossen, ed. Xavier Tilliette [Torino 1974], 200–1.)

Friedrich Tieck’s Bust of Schelling

Caroline writes on 21 February 1809:

“The sculptor will be doing a bust of Schelling, something the crown prince wants for his marble collection of great German men, about which you have probably already read in public newspapers, though in reality it includes some less great men as well. He chose Schelling alone from Munich and the Academy….a move which, as he himself says, will doubtless arouse at least some feelings of envy.”

Bettina Brentano then writes to Goethe during the spring of 1809:

“Friedrich Tieck is at present employed on Schelling’s bust; it will not be handsomer than he, — and therefore very ugly; and yet it is a beautiful work.”

(Bust by Friedrich Tieck in the in the Valhalla Commemorative Hall; repr. as frontispiece to Schelling als Persönlichkeit: Briefe, Reden, Aufsätze, ed. Otto Braun [Leipzig 1908].)

Maulbronn Monastery

Caroline and Schelling left Munich on 18 August 1809 for a period of rest and relaxation with his parents in the bucolic environs of Maulbronn in Württemberg, just northwest of Stuttgart, where his father was rector of the boarding school housed in the former monastery.

(Illustration: “Kloster Maulbronn,” Schwäbisches Taschenbuch auf das Jahr 1820 [Stuttgart].)

Schelling writes from Malbronn to Caroline’s brother Philipp Michaelis on 29 November 1809, after her death:

“Once, while standing at a window in Maulbronn, she said to me, ‘Schelling, do you think perhaps that I might die here?'”

(Evocative illustration from 1786 by Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, Oh perdez cette indifférence, et vous connoîtrez le vrai bien, from Isabelle de Montolieu’s novel Karoline von Lichtfield, published in the Gothaischer Hof Kalender zum Nutzen und Vergnügen eingerichtet auf das Jahr 1788; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur DChodowiecki AB 3.704 [1786].)

Schelling writes to Luise Gotter in September 1809:

“During a brief excursion from Maulbronn — to one of the most beautiful areas in the surrounding countryside here — which she also wanted to take but which — alas! I am now only too certain — contributed toward exhausting her energy despite the fact that such exercise and excursions otherwise usually strengthened her — during this entire excursion she was very quiet and withdrawn, and was so in a rather peculiar manner despite having an external appearance of the most perfect inner serenity.”

([1] Frontispiece to Bibliothek der Romane, vol. 13 [Riga 1786]; [2] Johann Christian Klingel, Frau mit Hut und Sonnenschirm [1781]; Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Graph. A1: 1372d.)

Maulbronn Ephorat

Maulbronn, Ephorat (headmaster’s residence), where Schelling’s father and mother lived when Schelling Sr. was headmaster, or Ephorus, at the school.

On 7 September 1809, Caroline died on either the third (the headmaster’s private residence) or second floor (the guest quarters).

(Undated photo, repr. in Carmen Kahn-Wallerstein, Schellings Frauen Caroline und Pauline [Bern 1959], plate following p. 176.)

Illustrations evoking the poignant situation in which Schelling along with his parents and brother found themselves during Caroline’s final hours.

([1] Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, Alexander sitzt auf Minchens Totenbett [1779]; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur DChodowiecki AB 3.313; (2) Aglaia: Jahrbuch für Frauenzimmer auf 1802; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung.)

Wake, funeral.

(Illustrations from Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, Höltys Elegie auf ein Landmädchen [1794]; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur DChodowiecki AB 3.985.)

Gottliebin Schelling

Schelling’s mother writes from Maulbronn in September 1809 to Meta Liebeskind, one of the original “University Mamsells,” thus also closing the circle, as it were, of Caroline’s life:

“Because my dear son is unable to direct his quill sufficiently to write, it falls to me, his elderly mother, to take on the painful task of informing you that his dear wife, our good Caroline, is no more. Oh, but how this news will pierce right through you.”

(Portrait: unknown artist, private collection of M. Bergfeld-von Schelling; repr. in Carmen Kahn-Wallerstein, Schellings Frauen Caroline und Pauline [Bern 1959], plate following p. 208.)

Maulbronn, Faust Tower and Former Cemetery

The obelisk Schelling had made to mark Caroline’s grave site in the former monks’ cemetery in the Maulbronn monastery was removed with all the other headstones during the nineteenth century and now stands elsewhere on the monastery property. Here, however, is a view from the back of the Ephorat, where Caroline died, across the former cemetery and toward the “Faust Tower.” Caroline is buried somewhere in this area still intersected by paths between the former grave sections.

(Postcard [1907].)