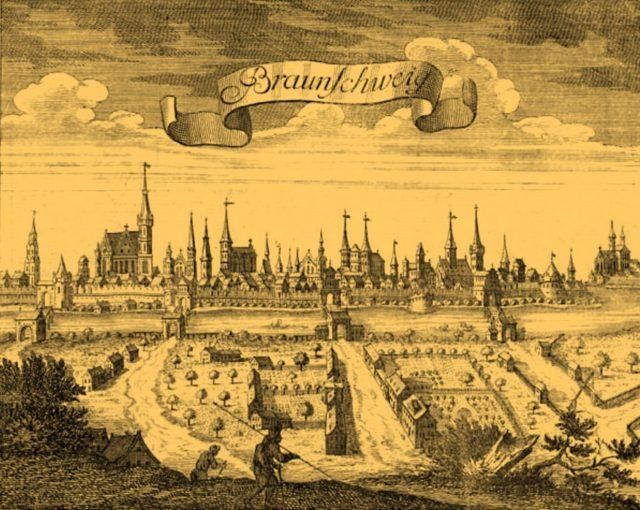

Braunschweig, 1746

Caroline and Wilhelm traveled to Braunschweig from Bamberg in October 1800 after Auguste’s death to live with Caroline’s sister, Luise. The choice of Braunschweig was determined not least by the fact that the government there would accept Caroline as a resident in the first place; her past in Mainz prevented her from moving to, among other places, Dresden.

(Braunschweig, 1746 copper engraving from Schau-Platz, Von drey und neuntzig berühmten Städten, So wol Jn Holland, Flandern und Brabant, als auch in Ober- und Nieder-Sachsen, und dem Reich, Jmgleichen Ein Hundert und dreysig Figuren aus der Heydnischen Götter-Historie, Wie selbige von alten Zeiten her abgebildet und benennet worden. Denen Liebhabern … entworfen [Leipzig 1746], plate 12.)

Braunschweig

Although Caroline managed to settle comfortably enough in Braunschweig, her relationship with Wilhelm was not entirely without issues. Before leaving for Berlin without Caroline in February 1801, Wilhelm apparently saw more of Elisa van Nuys in Braunschweig than Caroline wished. Caroline:

“Madame de Nuys had her portrait done by Anetti, but no one knows what happened to the picture. Some think you took it with you. Is that true?”

Caroline would remain in Braunschweig until April 1801, then return to Jena — without Wilhelm.

(Franz Alt, Braunschweig [1879].)

Caroline’s letter to Goethe

Caroline writes to Goethe on 26 November 1800 concerning Schelling’s depressed state of mind:

“If your own hopes in Schelling, if everything he has already accomplished — indeed, if he himself is as dear and as precious to you as I believe he is, then despite their peculiar nature you will surely pardon these lines in which I am asking you to help him. I know of no one else in the world besides you who could do that now. A series of grievous events has plunged him into an emotional state that could not but destroy him even were his original intention not necessarily to destroy himself by giving in to such a state etc.”

Schelling returned to Weimar with Goethe on 26 December 1800, dined with Goethe and Schiller there on New Year’s Eve, and then rang in the new year privately in a back room with them and Henrik Steffens, where “several bouteilles of champagne were waiting on the table . . . Goethe was loose and merry, indeed high-spirited, whereas Schiller became increasingly more serious.”

[Manuscript facsimile from Erich Schmidt’s 1913 edition of Caroline’s letters, vol. 2, following page. 18.)

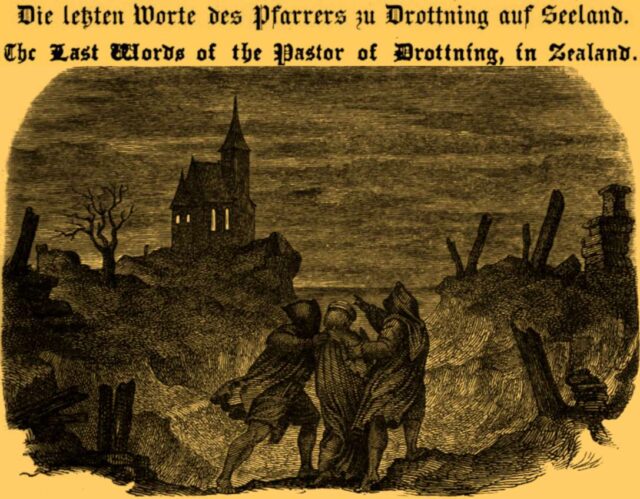

The Pastor of Drottning

Caroline writes on 2 January 1801 concerning their New Year’s celebration and the surprise reading of Schelling’s anonymous and eerie “The Last Words of the Pastor of Drottning”:

“Yesterday we did manage to do something for the new era: Herr and Madam Schlegel gave a souper of an extremely sophisticated kind, with sophisticated guests, sophisticated food, sophisticated wines, sophisticated spirit and wit . . . But listen, let me not conceal from you that the “Pastor” was also read aloud, and not a single person escaped the tremendous effect of this rather incorrect poem. . . . Schlegel himself, who read it aloud, was once again completely captivated by it, and I began to tremble.”

After a prologue, the “pastor’s” account begins: “‘Twas on a Sabbath even, at Christmas-tide. / I watched within my dwelling, through whose drear / Cold rooms the melancholy nightwind sighed / In fitful tones, that fell upon mine ear / Almost like wailings of a soul in sorrow.”

”

([1] Title vignette [in Fraktur] from the “The Last Words of the Pastor of Drottning, in Zealand,” translated by James Clarence Mangan as part of his “Stray Leaflets from the German Oak — Seventh Drift,” Dublin University Magazine. Literary and Political Journal 26, July–December 1845 [Dublin 1845], no. 152 [August 1845], 145–48; [2] illustration below that title vignette from Adolf Ehrhardt, Theobald von Oer, Hermann Plüddemann, Ludwig Richter, and Carl Schurig, Deutsches Balladenbuch, mit Holzschnitten nach Zeichnungen, 2nd ed. [Leipzig 1858], 191 [original German poem on 191–97].)

Luise Wiedemann

Caroline’s younger sister, who had married into the Braunschweig family Wiedemann. Caroline stayed with her after Auguste’s death but then, barely eight months later, witnessed Luise’s own child’s death in March 1801:

“I have again suffered a violent blow…It was almost more than I could bear, being reminded in this way, and having to see all the pain. Yesterday morning it was a week since I took the beautiful, precious child from its mother…and could hardly keep it in my arms it was so lively. Half an hour later, it was taken to its room, howling, and then not brought out again until it had slumbered into death.”

(Otto Cramer Family Archives; courtesy of Martin Reulecke.)

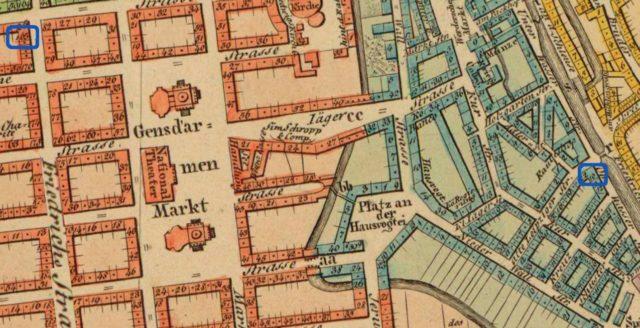

Berlin, 1826

Wilhelm Schlegel departed Braunschweig for Berlin on 21 February 1801 — without Caroline — and during his initial time in Berlin lived at Friedrichsstrasse 165 (top left), possibly in an apartment or furnished room secured for him ahead of time by Schleiermacher and conveniently located near the theater (center left). Wilhelm gave up that apartment at latest by early May and (fatefully) moved in with August Ferdinand Bernhardi and his wife, Sophie Bernhardi, at Jungerfernbrücke 10/Oberwasserstrasse 10 (center right).

(D. G. Reymann, Neuester Grundriss von Berlin [1826].)

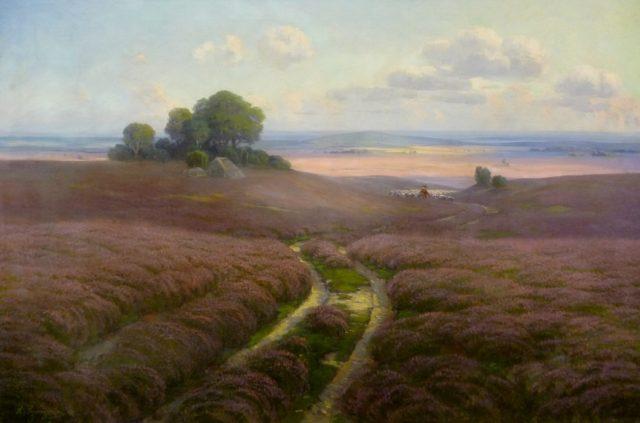

Lüneburg Heath

In early April 1801, while living in Braunschweig, Caroline visited her brother Philipp Michaelis in Harburg, just south of Hamburg. To get there, she and her traveling companions traversed the grand and beautiful Lüneburg Heath. She recounts — confirming once more her peculiar lack of receptivity to landscapes:

“I became seasick from the monotony of the heath and sky, which is the same from Braunschweig all the way here, a single 135 km stretch, nothing but scraggy, brown heath, sand, stunted trees covered with moss and mold.”

(Arnold Lyongrün, Auf blühender Heide bei Wilsede [1910].)

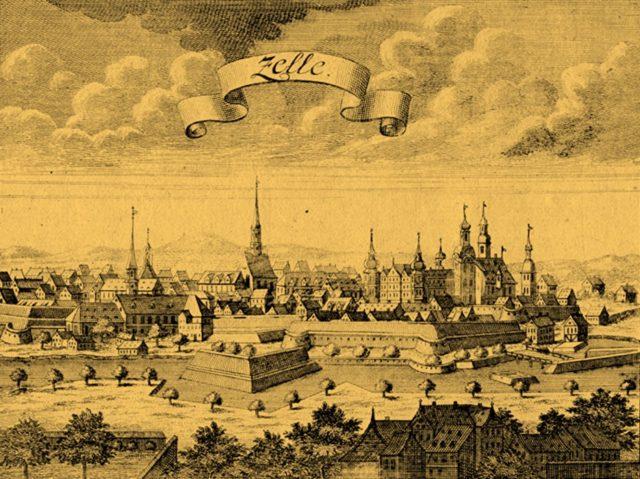

Zelle, 1746

On the way to Harburg, Caroline and her traveling companions stopped in the town of Celle (Zelle), where they visited with Caroline’s old acquaintance from her Clausthal days, Georg Christoph Dahme, as well as her former brother-in-law Justus Ludwig Bechtold Böhmer and the writer Emilie von Berlepsch.

(Celle, 1746 copper engraving from Schau-Platz, Von drey und neuntzig berühmten Städten, So wol Jn Holland, Flandern und Brabant, als auch in Ober- und Nieder-Sachsen, und dem Reich, Jmgleichen Ein Hundert und dreysig Figuren aus der Heydnischen Götter-Historie, Wie selbige von alten Zeiten her abgebildet und benennet worden. Denen Liebhabern … entworfen [Leipzig 1746].)

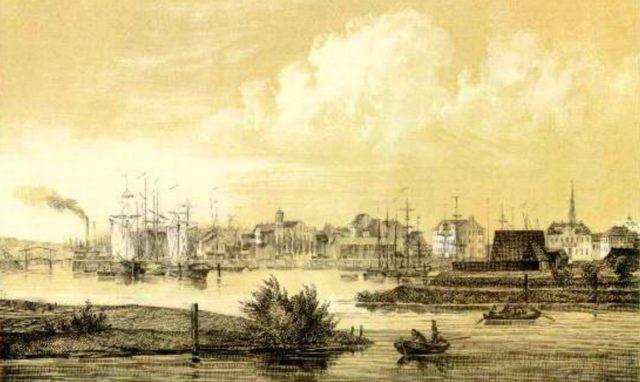

Harburg

After arriving in Harburg, just across the river Elbe from Hamburg, Caroline once more attests her, in this case, morose insensitivity to natural landscapes:

“Here, too, the shoreline is anything but beautiful, and the view of Hamburg exists really only as an idea. I will see it up close the day after tomorrow…If I drown in the Elbe tomorrow, remember that today I sensed it would happen.”

(Lithograph by Robert Geissler, Harburg: Gesamtansicht von der Neuländer Fähre aus gesehen [ca. 1850].)

Hamburg, 17th Century

Caroline, of course, did not drown as she imagined, and instead visited acquaintances and relatives and attended the French theater in Hamburg. She stayed first in Altona and then with the family of Friedrich Johann Lorenz Meyer, the same Canon Meyer who had been present when Caroline, Lotte Michaelis, and a certain student by the name of Frankenberg had “cavorted in an unseemly manner” in a barn outside Göttingen back in 1783.

(Painting by unknown artist.)

Susanne von Bandemer

Caroline attended a déjeuner given by a certain Madame de Sierstorff in Braunschweig also attended by this poetess. Caroline recounts the gathering itself:

“Madam de Sierstorf told Madam von Bandemer that Madam von Haugwitz (wife of the Prussian minister) was here, had heard that she was passing through, and would be coming to speak with her. Well, the poetess was completely beside herself at this news, and then Madam von Haugwitz genuinely did arrive, and now there was a whole spectacle of insipidness and subalternity and self-conceit and sentimentality — and I was as amused as if I had been at the choicest little French comedy. . . . An innocent little pastor’s daughter from the city came with the permission of Madam de Sierstorf so that she, too, might make the acquaintance of Madam Susanne. Ah, but she had heard so much about her, since her uncle allegedly also ate with her in the Blue Angel, where they really did spend such magnificent evenings, and Mademoiselle Kirchgessner was there and the harmony of the spheres and all of them allegedly just so blissfully blissful etc. Just try to imagine all this wretched stuff.”

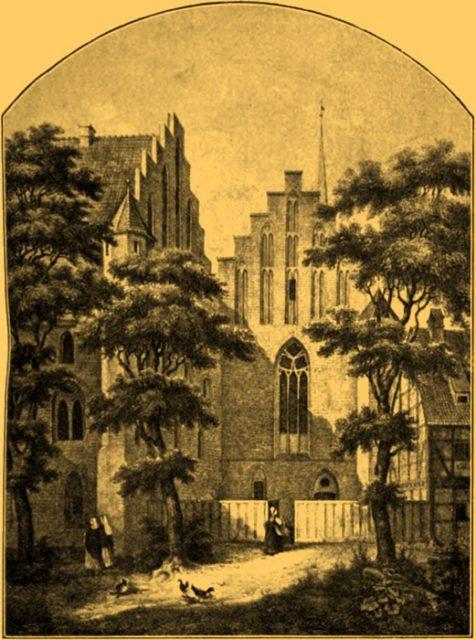

Wienhausen Convent

On 16 April 1801, Caroline departed Harburg to return to Braunschweig but first met her mother in Celle, who then traveled back to Harburg to stay permanently with Philipp Michaelis. During this stopover in Celle, Caroline along with her sister Luise Wiedemann, the latter’s daughter, Emma, and her mother again visited the family of Christoph Dahme. Chanoinesse Louise Schläger, an acquaintance from Caroline’s very early period in Gotha, is also there. Caroline and her companions accompany her back to her convent in Wienhausen just outside Celle. The chanoinesse will visit Caroline in Jena in August 1802.

(O. Vorlaender, “Ein Klostermuseum in der Heide,” Die Denkmalpflege 4 [1902] 14 [5 November 1902], 109–13, here 109.)