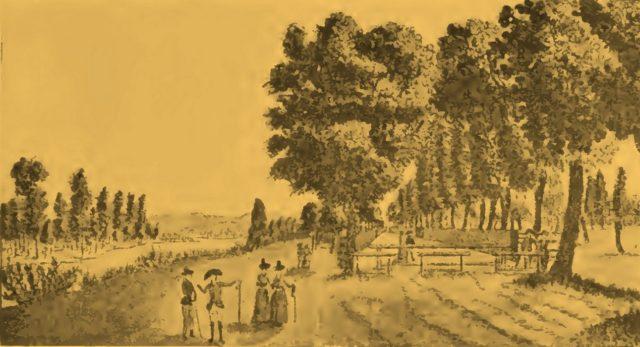

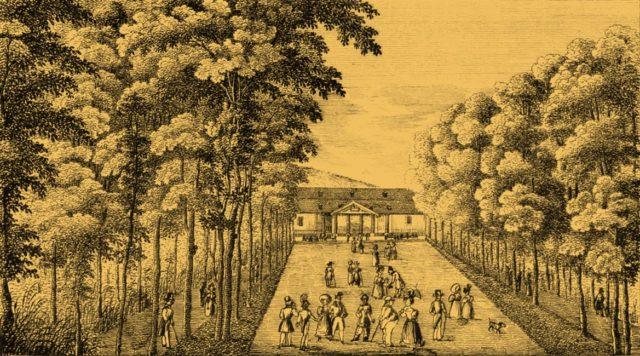

Paradise Greenspace in Jena

Dorothea Veit writes in a letter to Schleiermacher in November 1799:

“Yesterday afternoon I was in Paradise (that’s what they call a certain promenade here) with the Schlegels, Caroline, Schelling, Hardenberg [Novalis], and one of his brothers…and who should suddenly appear coming down the hill? none other than his old Divine Excellency, Goethe himself…Wilhelm introduces me to him, he pays me a very nice compliment…and is cordial and charming, and all ease and attentiveness toward his devoted lady servant…But since Wilhelm could not really get any conversation going, I thought to myself: well the devil take modesty; if he is bored then I have irrevocably lost my opportunity! So I immediately asked him something about the rushing currents in the Saale River, he responded with an explanation, and thus we continued on in a lively manner.”

(Ernst Borkowsky, Das alte Jena und seine Universität [Jena 1908], 125.)

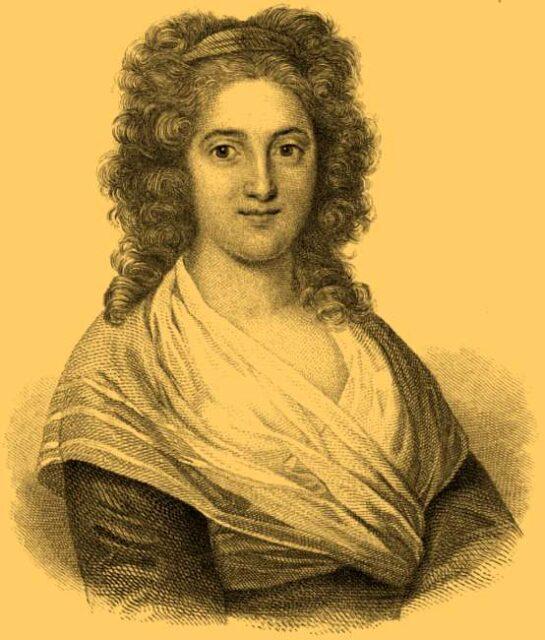

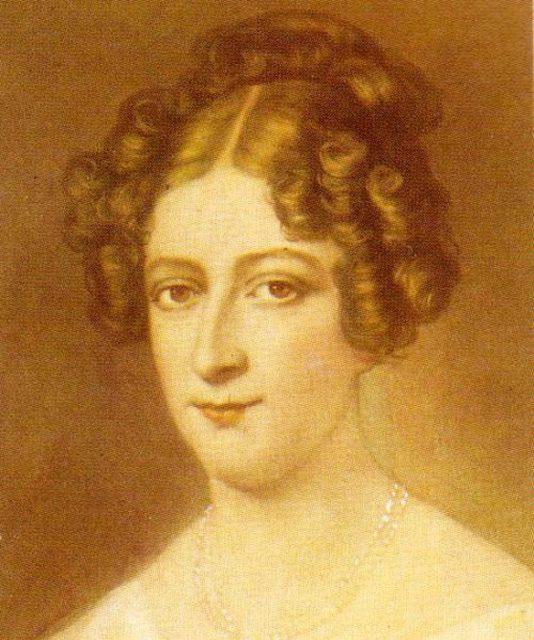

Henriette Herz

The Berlin salonnière in whose literary circle Friedrich Schlegel and Dorothea Veit met. Though Caroline did not know her, Dorothea mentions her often in her own letters, and Henriette’s memoirs offer revealing insights about Dorothea and the period.

(Portrait: after Anton Graff [1792]; frontispiece to her memoirs, Henriette Herz: Ihr Leben und ihre Erinnerungen, ed. J.Fürst [Berlin 1858].)

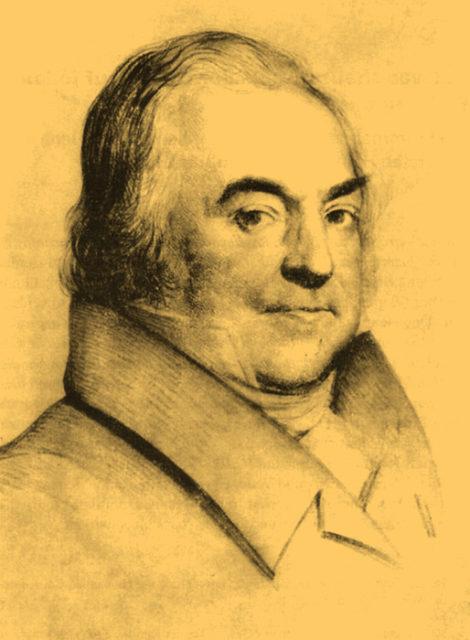

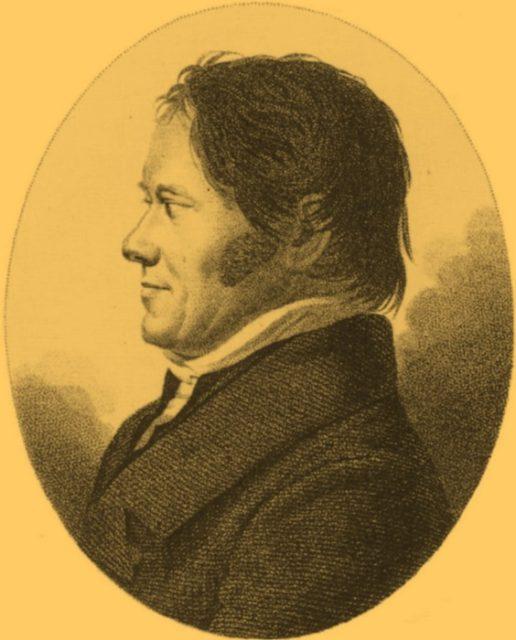

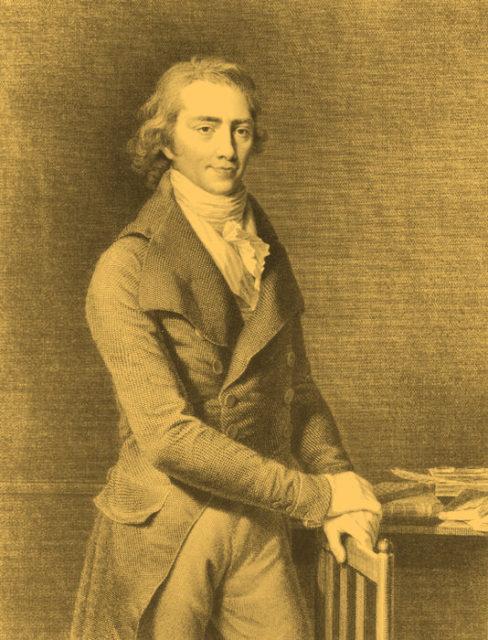

Carl Friedrich Ernst Frommann

Carl Friedrich Ernst Frommann: Jena publisher with whom the Jena Romantic circle had extensive contacts, both business and social, though he did become decidedly impatient with Friedrich Schlegel’s inertia. Caroline to Wilhelm in 1802:

“By contrast, the Frommanns cannot praise you enough; really, at this point you could do whatever you wanted, indeed whatever you were capable of, and you would still be viewed as a jewel of uprightness, as also Schelling.”

(Portrait by J. J. Schmeller [1830].)

Triesnitz

Triesnitz (with various spellings), originally a rural area on the southern edge of Winzerla, southwest of Jena proper, and in the eighteenth century a popular excursion locale for “academic Jena. Wilhelm Schlegel writes to J. D. Gries in May 1799:

“Yesterday Stakelberg gave a grand, well-attended diné on the Driesnitz, which was very nice indeed — as it were, the first spring excursion. All sorts of people gathered together there, the Hufelands, Pauluses, Loders, Fichtes, Frommanns, and — Kotzebues! I have now both seen and spoken with this wooden idol, who appears inestimably common, lame, and Philistine.”

(Christian Gotthilf Immanuel Oehme, In der Trießnitz um 1780; Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden; also Jena Stadtmuseum.)

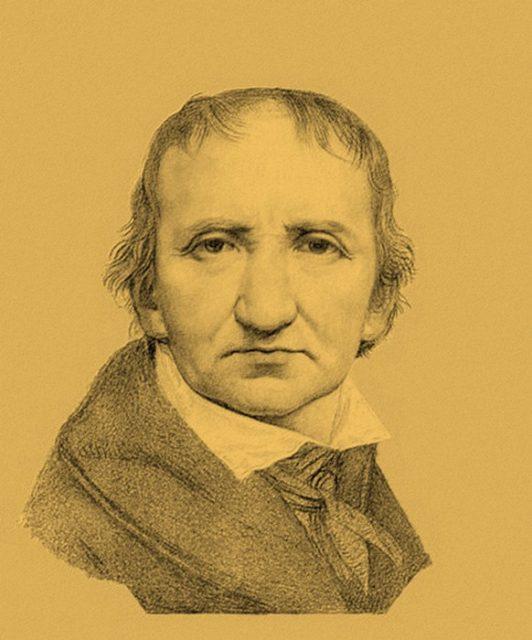

Dorothea Veit

Auguste, in Dessau at the time, writes to a friend in November 1799:

“You probably already know from my mother what pleasant company we have had in Jena this winter. First, Fritz [Friedrich Schlegel] is there from Berlin, and then a lady from Berlin, Madam Veit, is living downstairs in our house; I have not met her yet, but Mother writes that she is quite amiable.”

(Pencil drawing from the Varnhagen Collection; in Briefe von und an Friedrich und Dorothea Schlegel, ed. Josef Körner [Berlin 1926], plate following p. 24.)

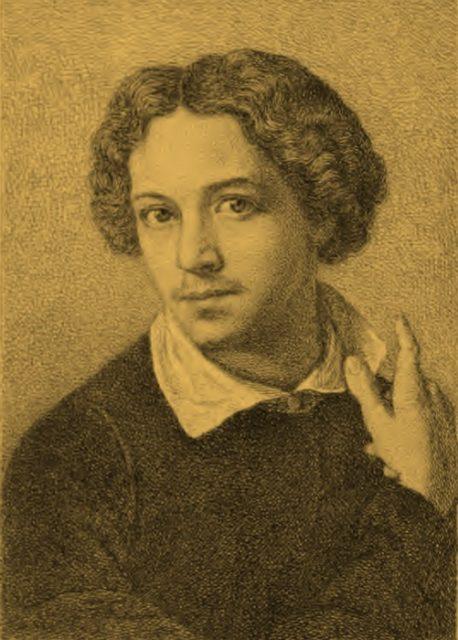

Philipp Veit

Philipp Veit, self-portrait during a later period. Caroline continues in her letter on 6 October 1799 to Auguste after Dorothea and Philipp’s arrival in Jena (Dorothea’s son Johannes remained in Berlin with his father):

“And you have no need to fear the little boy any longer, c’est un joli petit espiègle who will give you loads of fun; indeed, I have already become great friends with him. He is small and supple like a page; we will want to put your livery [from an amateur theater performance] on him.”

(Portrait from Dorothea v. Schlegel geb. Mendelssohn und deren Söhne Johannes und Philipp Veit, 2 vols., ed. J. M. Raich [Mainz 1881], vol. 2, plate following p. 128.)

Dorothea Veit, newly arrived in Jena, writes to Schleiermacher in October 1799 about the relationship between Caroline and Wilhelm Schlegel:

“One does not notice much evidence of the sacrament; they live together more as loving friends who are together voluntarily. But their petty quarrels, which sometimes can go quite far indeed, make me quite anxious; Caroline laughs at me on this account, but every time one arises I simply have to get away.”

Caroline Wilken, née Tischbein mentions a similar scene from the summer or autumn of 1799:

“A relationship had developed between Schelling and his hostess under which [Wilhelm] Schlegel suffered greatly. I can still recall that after a modest ball at the Schlegels’ home, after all the guests had departed and I myself had returned to the hall to fetch something or other, Schlegel and his wife strode in together quite agitated. He was weeping, while she looked extremely resolute and flushed with anger.”

(Frontispiece to [?] Koch and Johann Jacob Wagner, Abendmusse zweier Freunde, vol. 3 [Leipzig 1794].)

Dorothea writes to Schleiermacher about Auguste in May 1800:

“Auguste is an extremely amiable creature who clings to her mother with the most ardent affection — which is precisely also her great misfortune, since she depends wholly on her mother instead of thinking for herself. She has also already been completely ruined, thinks of nothing but her external appearance.”

(Frontispiece to Moritz August von Thümmel, Reise in die mittäglichen Provinzen von Frankreich im Jahr 1785 bis 1786, vol. 4 [Leipzig 1810].)

Henrik Steffens

The Norwegian was another of the scientists associated with the Jena circle — if less bizarre than Ritter — and a lifelong admirer of Schelling. There is some evidence that he was romantically interested in Auguste. He was in any case almost speechless with grief after her death.

(Portrait: unknown artist; Frederiksborgmuseet.)

Johann Christian Stark

Prominent physician in Jena, personal physician of the ducal family in Weimar, of Schiller and Goethe, and also treated Friedrich von Hardenberg (Novalis) and his fiancée Sophie von Kühn. Caroline recommended Stark to Hardenberg to treat his second fiancée, Julie von Charpentier.

(Portrait: frontispiece to vol. 1 of Johann Christian Stark, Handbuch zur Kenntnis und Heilung innerer Krankheiten des menschlichen Körpers [Jena 1799].)

Dorothea Veit

Dorothea Veit. Caroline writes to Auguste after Dorothea’s arrival on 6 October 1799:

“She does not seem pretty to me; her eyes are large and glowing, but the lower part of her face is too slack, too pronounced. She is no taller than I am, perhaps a bit broader. Her voice is the gentlest, most feminine thing about her. That I will grow fond of her I do not doubt for a moment.”

(Portrait from Dorothea v. Schlegel geb. Mendelssohn und deren Söhne Johannes und Philipp Veit, 2 vols., ed. J. M. Raich [Mainz 1881], frontispiece to vol. 1.)

Louise Seidler

Later an artist of some note, Louise Seidler recounts vignettes of her confirmation instruction with Auguste in Jena:

“I fell flat onto the ice, tall and gangly, with my Bible, hymnal, and catechism books flying everywhere.”

Her letters and memoirs are also otherwise an important source of information about life in Jena at the time.

(Self-portrait; SLUB / Deutsche Fotothek; df_hauptkatalog_0102906.)

Ludwig Tieck

Though he did not publish anything in the periodical Athenaeum, Ludwig Tieck was nonetheless part of the early Romantic circle proper, living in Jena during the winter of 1799–1800 with his wife, Amalie. “Malchen” does, however, come in for some rather unkind criticism by others in the group, and apparently by Tieck himself.

(Portrait by Joseph Karl Stieler.)

Caroline writes to Auguste in October 1799:

“So Wilhelm and Tiek sat down yesterday evening and presented him [their resolute Berlin adversary Garlieb Merkel] with a despicable sonnet. What a celebration it was to watch their brown eyes flashing sparks across the room and with what cheerful boisterousness this wholly justified malice was perpetrated! Madam Veit and I were almost rolling on the floor with laughter.”

(Frontispiece to August Lafontaine, Rudolph und Julie,, vol. 1 [Halle 1801].)

Puss in Boots

In 1797 Ludwig Tieck published a boisterously humorous fairy tale in burlesque dramatic form based on the figure of Puss in Boots from Charles Perrault. Once when Tieck entered the room, Auguste quipped:

“What? You come in through the door? I would sooner expect you to come striding in like your cat, across the rooftops.”

(Illustration from the original edition of Charles Perrault, Histoires ou contes du temps passe: Avec des moralitez [Paris 1697], 83.)

Friedrich Schlegel

In early September 1799, Friedrich Schlegel arrived back in Jena — before Dorothea — and took up residence with Caroline and Wilhelm Schlegel in their house on Leutragasse. Problems quickly emerged when he and Dorothea noticed Caroline’s interest in Schelling.

(Portrait: 1799, by F. Gareis.)

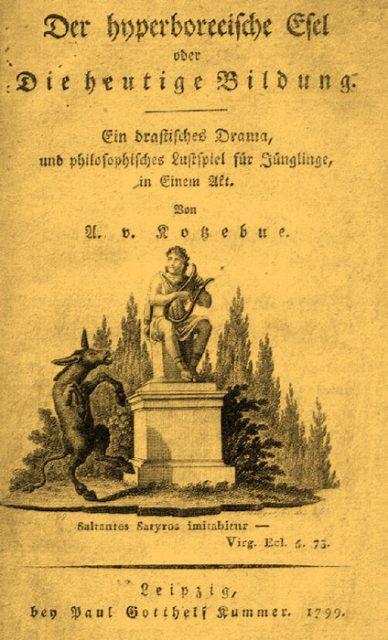

The hyperborean Ass

Auguste von Kotzebue’s romantic satire Der hyperboreeische Esel (Leipzig 1799) lampooned the Schlegels’ Athenaeum by incorporating direct quotes from Friedrich Schlegel’s fragments into the accordingly nonsensical dialogue. Although Wilhelm Schlegel arrived too late in Leipzig for the performance, Friedrich did attend. The play was immediately banned.

The appended quote from Virgil [Eclogues 5:73] refers to “imitating the leaps of the satyrs.”

In the following sample dialogue snippet, Karl (who has read Athenaeum) is speaking to the concerned prince:

Prince. I can now see where this conversation is headed. Let me give you some well-meaning advice, namely, not to have anything to do with state administration, at least not in my own land, where peace and morality rule.

Karl. Morality? I hardly believe that. The first impulse of morality is to oppose positive legality and conventional justice.

Prince. That sounds quite like the utterly destructive principles of more recent times.

Karl. It is natural that the French should more or less dominate the age. They are a chemical nation; likewise, the age is also a chemical one etc.

Johann Wilhelm Ritter

In some ways the mad scientist of the Jena circle and the source of some of the most interesting if bizarre events and material associated with the group, including investigations of such phenomena as dowsers and raising the dead through galvanic columns. Caroline to Novalis in 1799:

“What can I tell to you about Ritter? He is living in Belvedere and is always sending frogs over here, of which there is a surplus there and a lack here.”

(Portrait reproduced in Stanley Finger, Marco Piccolino, and Frank W Stahnisch, “Alexander von Humboldt: Galvanism, Animal Electricity, and Self-Experimentation Part 1: Formative Years, Naturphilosophie, and Galvanism,” Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 22(3) [April 2013], albeit without attribution.)

Johann Gottfried Schadow

This prominent Berlin sculptor and artist, though consulted on Auguste’s monument, eventually came into conflict with the emergent Romantic movement in the arts as represented not least by his own pupils, including Friedrich Tieck. Object of some of Wilhelm Schlegel’s critical public needling.

Rahel Levin

Dorothea’s letters to this Berlin salonnière provide considerable, often detailed information about the Jena circle, though also often less than complementary:

“You think Caroline Schlegel is not hard? Well, you are wrong, even had you never been wrong before. Hard, hard as stone; we — you and I, my love — are soft as silk compared to Caroline!”

(Portrait by Moritz Michael Daffinger.)

Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland

Jena physician as Caroline would have known him. Attended the Duke of Weimar, Goethe, Schiller, Wieland, Herder, and also Caroline during her intense bout of “nervous fever” during the late winter and early spring of 1800. Only after being badgered by Schelling did Hufeland agree to treat Caroline according to the “Brunonian method.”

(Portrait, 1802, after Johann Friedrich August Tischbein; plate 11 from J. F. Frauenholz Suite der Staatsmänner und Gelehrten [Nürnberg 1795–1809].)

Visit to an Apothecary

Dorothea Veit writes on 15 May 1800 about Caroline’s illness during the spring of 1800, an illness that prompted the decision to seek out a mineral-springs cure:

“I would, however, consider it abominable, and thus utterly impossible, that she, who always went on and on so enthusiastically about ‘nature’ and about the ‘beautiful area’ around here, that precisely she would be capable of spending this entire, divine spring in bed, in a closed room, morose, and amid all sorts of disgusting smells and arrangements, merely to create a mask with which she might then be able to exit.”

“Disgusting smells,” that is, not least from apothecary concoctions.

(Schauplatz der Natur und der Künste, vol. 4 [Vienna 1776], plate 34):

Bamberg

Bamberg, in Upper Franconia on the river Regnitz: Caroline, Auguste, and Schelling spent several weeks here in May and June 1800 before Caroline and Auguste continued on to nearby Bocklet, where Auguste died on 12 July 1800. Wilhelm Schlegel arrived shortly after her death and remained in Bamberg with Caroline and Schelling during that late summer and early fall.

(Ludwig Lange and Ernst Rauch, Original-Ansichten der vornehmsten Städte in Deutschland, ihrer wichtigsten Dome, Kirchen, und sonstigen Baudenkmäler alter und neuer Zeit: nach der Natur aufgenommen [Darmstadt 1832], plate 25).

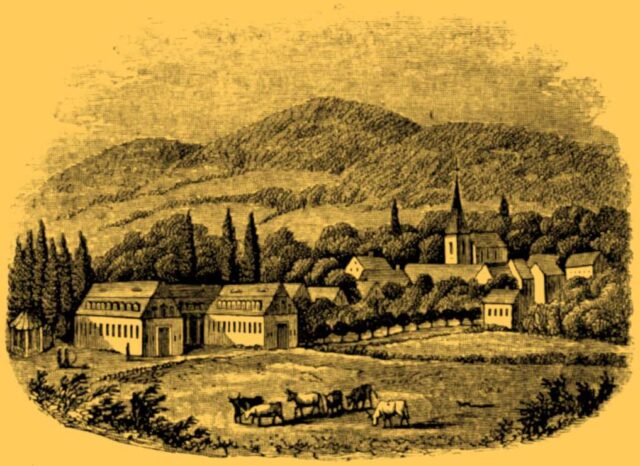

Bocklet in 1831

Bocklet on the Franconian Saale River, where Auguste died on 12 July 1800 and is buried. Wilhelm writes to J.D. Gries on 7 July 1800 to explain the name:

“I am so sorry, my dear friend, for causing your divinatory acumen to be so laboriously and moroever also so futilely taxed. It was, however, no doubt less a matter of my own handwriting than that you simply did not want to believe that the name of the locale really was exactly as you read it, and then also a problem with your geographical, statistical, and topographical books, which contained no reference to it. Said mineral spring and spa resort is called Bocklet, written bocklet, Bocklet βοκλετ, and is located near Schweinfurt in Franconia, which you will want to add to the address if, for example, you are writing to Caroline. She will be staying there until toward the end of July, and has described the setting and surrounding area there as being quite pleasant.”

(Illustration by J. B. C. Foerisch, frontispiece to C. J. Haus, Bocklet und seine Heilquellen für Aerzte und Nichtärzte [Würzburg 1831].)

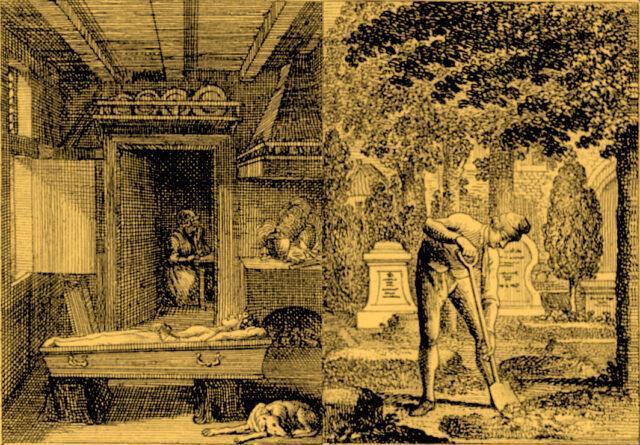

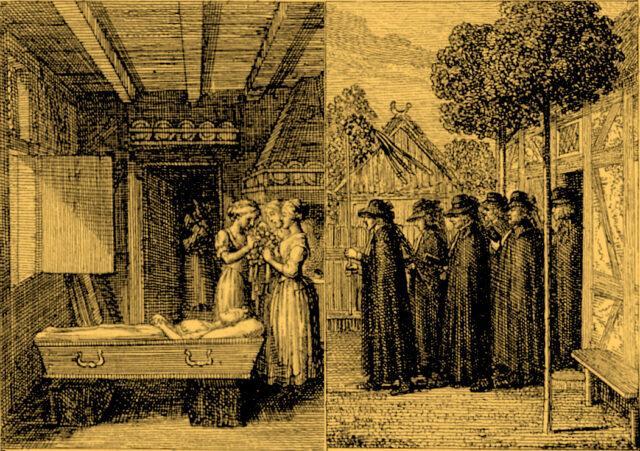

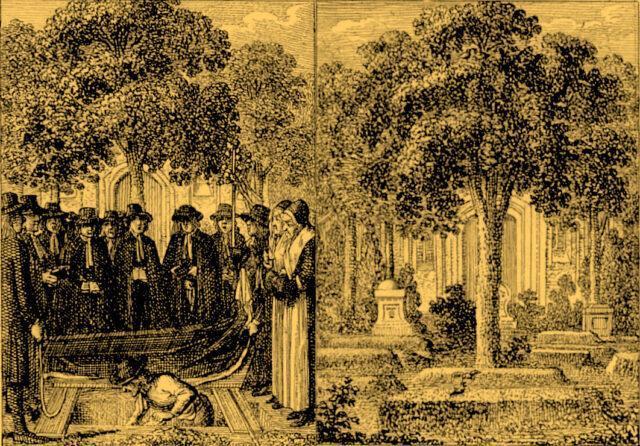

Death and funeral of a young woman in a rural setting

Auguste died in the small village of Bocklet on 12 July 1800 and seems to have been buried shortly thereafter in the small church cemetery overlooking the valley.

(Illustrations by Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, portraying the death and funeral of a young woman in a typical rural setting in Germany at the time, accompany Ludwig Hölty’s (1746–76) “Elegie auf ein Landmädchen” (1774); Höltys Elegie auf ein Landmädchen (1794); Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur DChodowiecki AB 3.985.)

Death and funeral of a young woman in a rural setting

Death and funeral of a young woman in a rural setting

Bocklet, 1837

Wilhelm Schlegel writes:

“I recently made my first pilgrimage to her grave. It is located … in a narrow, enclosed, cheerful valley that gives no hint of graves; she lies in a narrow and poor village cemetery, which is, however, situated out in the open and from which one can look out onto the beautiful valley.”

Auguste is buried in the cemetery of the church at right.

(Illustration from “the author of ‘St. Petersburgh,'” The Spas of Germany, 2 vols. [London 1837], 1:322.)

When Schelling returned from an impromptu visit to Swabia with his parents after his brother had died during the fighting in Genua, he found that although Caroline had much improved with her own illness, Auguste was now quite ill and Caroline understandably upset.

(Frontispiece to Wilhelm und Karoline: Eine wahre Geschichte [Leipzig 1782].)

Auguste’s tragic, hitherto inconceivable loss constituted a defining moment in Caroline’s life. Wilhelm Schlegel writes to Goethe a week after her death:

“Her mother’s health, which had recovered almost completely, has now been devastated anew, and I must fear the worst.”

(Frontispiece to August Lafontaine, Der Sonderling: Gemälde des menschlichen Herzens, vol. 2 [Berlin 1800].)

Auguste’s death constituted a defining moment, perhaps the defining moment in Caroline’s life.

(Taschenbuch auf das Jahr 1802: Der Liebe und Freundschaft gewidmet; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung.)