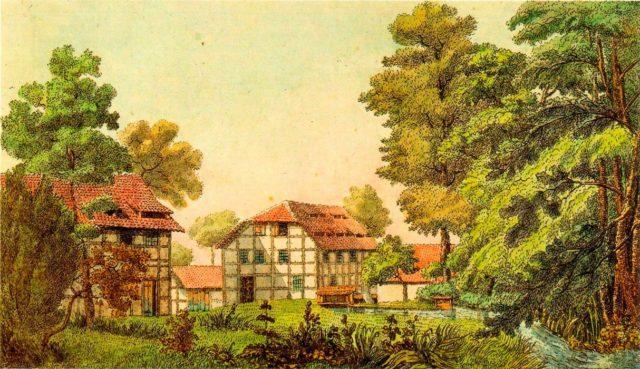

Paper Mill in Weende

The Paper Mill in Weende, north of Göttingen, a popular excursion locale Caroline visited with her brother Fritz and Therese Heyne in May 1784:

“One morning the three of us went to the Paper Mill, where we spent 6 very enjoyable hours. As an aside, let me tell you about a company of people we encountered there. A certain Madam Elise Bethmann from Frankfurt is currently staying here to have her child’s illness treated…Her husband is Germany’s premier banquier. Of course, she cannot stand him, since she herself does not really make anything of the uncertainty of wealth…She speaks disparagingly about her husband and is a poor teacher, e.g., pinching her children in public; and yet she is knitting money purses for forty of her intimate lady friends.” One of those children, Sophie, would prove instrumental in securing Caroline’s release from prison in 1793.

(Watercolor by Christian Andreas Besemann, ca. 1795—1800.)

Botanical Garden in Göttingen

Caroline writes on 2 March 1782:

“That same evening, just when everyone was expecting the greatest trouble, someone cried ‘fire,’ the drummer began beating his drum, the bells sounded, and we learned simultaneously that the fire was allegedly in the prorector’s house. It was indeed there, in the orangery of his botanical garden, but was quickly extinguished. It was extremely cold, with the wind blowing toward the city, and since the students would not have helped, Göttingen could easily have been lost. But everything is tranquil at the moment.”

(Illustration: 1758 engraving.)

Michaelis Siblings

Representative illustration of the basic configuration of the Michaelis siblings during the 1780s except for stepbrother Fritz (born 1754), who was already a physician: the three daughters — now young women — Luise (born 1770), Lotte (born 1766), and Caroline (born 1763), and their brother Philipp (born 1768).

(Johann Caspar Lavater, Geheimes Tagebuch, 2 vols. [Leipzig 1771, 1773], 1:130.)

Caroline seeks comfort in God

In 1781, young Caroline seeks comfort in God after being hurt and insulted in a petty intrigue instigated by Therese Heyne and a Göttingen student:

“I soon collapsed from all the pain and torment, but, O, Religion, thou Consoler of the utterly inconsolable! Thanks to you, I did not utterly despair and have once again attained a measure of peace. God improved my heart and took me to his bosom..”

(Frontispi8ece to W. G. Becker, Darstellungen, vol. 1 [Leipzig 1798].)

Lotte Michaelis

Caroline’s sister Charlotte (Lotte) Michaelis. Silhouette from the album of Gregorius Franz von Berzeviczy (1763–1822), who studied in Göttingen during the years 1784–86. If the silhouette was genuinely done during those years, Lotte would have been between 18 and 20 years old at the time (born 1766).

(Portrait: silhouette by Gregorius Franz von Berzeviczy, in Gregorius Franz von Berzeviczy, Göttinger Profile zwischen Aufklärung und Romantik, ed. Erika Wagner and Ulrich Joost [Neustadt 2011].)

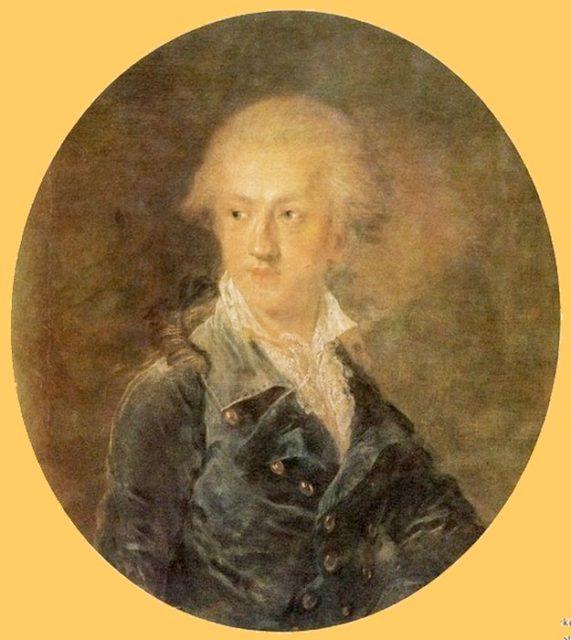

August Kotzebue

Kotzebue, a prolific playwright and actor who will appear frequently later as a nemesis of the Jena circle, was in 1781 and 1782 one of Lotte Michaelis’s suitors, passing secret letters along to her through a friend:

“Please be careful not to confuse these girls when you pass the letter along. Her name is Lotte, she has black eyes, long eyelashes, looks like an angel, and is not very tall…It is imperative that not a single soul learn anything about either the letter or the entire matter.”

(Portrait: unknown artist.)

House von August Ludwig von Schlözer in Göttingen

In April 1782, Caroline and Frau Schlözer accompanied Herr Schlözer and Dorothea from Kassel back to Göttingen after the latters’ six-month tour of Italy:

“We finally arrived quite splendidly in Göttingen, if I do say so myself: 3 on horseback leading the way, then our carriage with 4 passengers, the Roman Travel Society with 6 horses, and a cabriolet bringing up the rear. Our entourage grew such that when we finally got out in front of the Schlözer’s house, over 100 people had assembled, and Schlözer was almost carried into the house and we ourselves had trouble pushing our way through the crowd.”

(Drawing by Louise von Schlözer; SUB Göttingen: Schlözer-Stiftung, Bilder AL 145.)

Kerstlingeröderfeld, ca. 1800

Kerstlingeröderfeld estate outside Göttingen served as a tavern for visitors.

Therese Heyne writes to a friend on 1 March 1783:

“Just to pass the time, let me relate a scandalous story to you that would sound quite silly were young people not usually so careless as to give something of this sort a really malicious turn. Canon Meier is here just now to see his enchanting Friederike, and on Thursday they traveled out to Kerslingerode [Kerstlingeröderfeld], including with a certain Frankenberg, who is constantly visiting the family. The Böhmers, Michaelises, Frankenberg, Meier, and several others. Unfortunately, Koskull, Schulenburg, and Poel were also there. The two Michaelis girls [Caroline and Lotte] took a walk with Frankenberg, and on their way back go into an open barn with lots of hay lying around, and there, as Koskull related, they cavorted in an indecent manner. Koskull went over and closed the door and blocked it with a big piece of wood.” —

(Unknown artist; copper engraving [ca. 1800].)

An “open barn with lots of hay lying around.”

Therese Heyne, who never passed up an opportunity to cast aspersions on Caroline’s character, continues disingenuously in her previous letter:

“How do you think this story might get turned and twisted were it to fall into the right hands?”

`

(P. Le Mesle, Suite d’estampes tirées des Contes de la Fontaine: Le cuvier [1743]; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur PFilloeul AB 2.2.)

Romanticized Abduction.

In February of 1783, Caroline writes to a friend about her homesickness for Gotha, where she had attended a boarding school for young women:

“On Sunday I received a letter from Wilhelmine that was quite entertaining and really, really made me laugh a lot, for I can imagine nothing more ridiculous than to be abducted like that. Indeed, even were it more serious and someone secretly whisked me off to Gotha in a chaise, I would not resist.”

(Title vignette to Christian August Wichmann, Das Frauenzimmer im dreyfachen Stande, als Tochter, Frau und Mutter: Eine wahre, moralisch-komische Geschichte, vol. 1, Das Mädchen, oder die Tochter [Breslau 1782].)

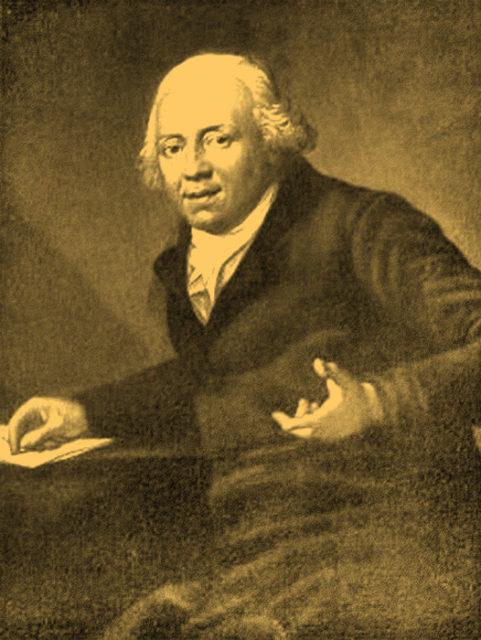

Friedrich Nicolai

Friedrich Nicolai, Berlin Enlightenment representative who dined with Caroline’s family in October 1781 during his tour of Germany. Eighteen-year-old Caroline writes:

“A man who certainly seems to possess a generous measure of genius, spirit, and finesse, but who despite all his savoir vivre would not know enough to conceal either his religious principles or the rather grand idea he has of himself.” Nicolai would later publish a satire of the Jena Romantic group featuring a Romantic coquette by the name of “Frau von C**.”

(Portrait by Anton Graff.)

Carl Eugen, Duke of Württemberg

Carl Eugen, Duke of Württemberg. Caroline continues her account in March 1781:

“Every other word he speaks is ‘virtue’ or ‘religion,’ he who oppresses feminine virtue, who shatters the peace of so many families…Oh, how I despise him! If you want to know what he looks like, then imagine a large man, not slender, with a reddish face, a big nose along with small ditos on it, large, protruding eyes, a short brown jacket, a sulfur-yellow vest so long that one could hardly see the black-satin leggings over which his gray stockings were wrapped in the old-fashioned style, for his vest and stockings overlapped, and finally boots that had been stiffened with whalebone, and who walks with the gait of an old man.”

(Oil painting by Jakob Friedrich Weckherlin.)

Franziska von Hohenheim

Franziska von Hohenheim, second wife — but initially mistress — of the Duke of Württemberg. Caroline in March 1781:

“This week the Duke of Württemberg and the Countess of Hohenheim — who is traveling with him — honored our city. He visited all the lectures…the library, disputations…everything one could think of…She went along, then spent the rest of the time at the inn being bored. Everyone who has seen her offers the most charming description; she is allegedly not beautiful but is extremely pleasant, learned, and endowed with ample good sense and understanding….He is ugly, and she is probably not really in love with him even though she left her husband for his sake.”

(Portrait by Jakob Friedrich Weckherlin.)

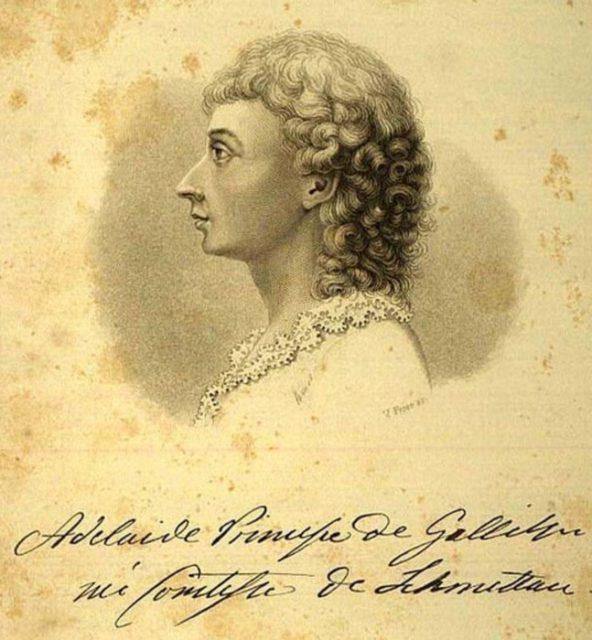

Amalie von Gallitzin

Amalie von Gallitzin: Eclectic, erudite follower of the Enlightenment and later salonnière in Münster. Caroline describes her in September 1781:

“We have had a visitor here who is quite singular, a certain princesse de Gallizin…An extremely knowledgeable woman, dressed in a sort of Greek drapery cloth, with short-trimmed hair, flat shoes…who goes to bathe with an entourage of 6 to 8 gentleman in broad daylight in our Leine River.”

(Portrait: by V. Froer, frontispiece to Mittheilungen aus dem Tagebuch und Briefwechsel der Fürstin Adelheid Amalia von Gallitzin nebst Fragmenten und einem Anhange [Stuttgart 1868].)

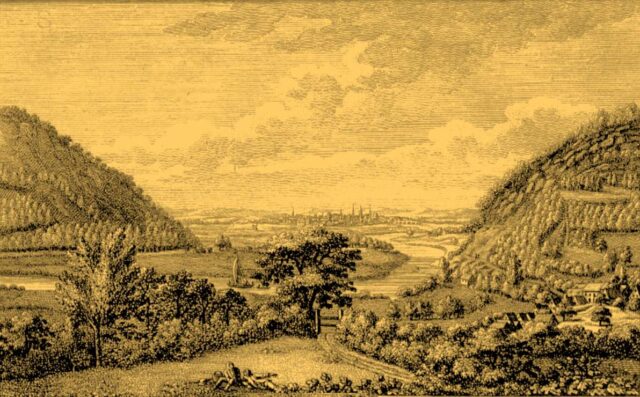

Hann. Münden

Hann. Münden, approaching from a distance, 21km southwest of Göttingen, where Caroline stopped with Madam Schlözer on their way to Kassel to meet Professor Schlözer and his daughter, Dorothea, on the latters’ return from Italy in April 1782. Caroline writes:

“On our way there, in Münden, we were also present at a peculiar but rather sad drama, namely, the embarkation of troops for America. What a broad, diverse, and yet dreadful departure scene. It is easy enough to understand what it mostly meant to me [Caroline’s brother Fritz had been a staff medical officer with the Hessian troops in America]. The area around Münden is so romantic that it seems to have been created for just such a scene. Although I have no need to tell you, my dear Luise, how much Kassel pleased me, I must say I was bothered by the notion that in Münden the landgrave [Friedrich II of Kassel] was selling human beings in order to build palaces in Kassel.”

(Münden in 1808; Göttingischer Taschen-Kalender für das Schalt-Jahr 1808.)

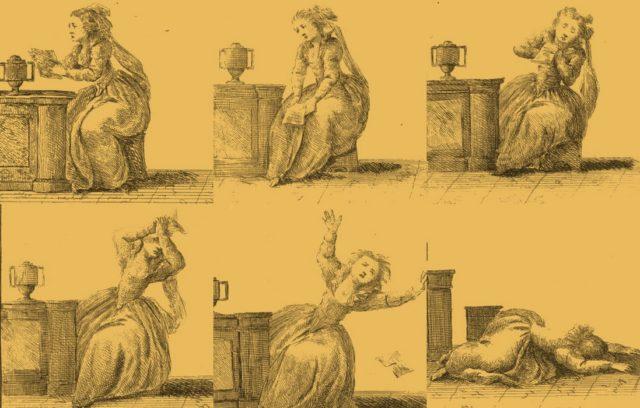

Lenardo und Blandine

Joseph Franz von Götz’s Lenardo und Blandine (1783), 160 engravings illustrating Gottfried August Bürger’s ballade by the same name (1776) almost after the fashion of modern comic-book panels. Caroline in April 1784:

“I recently saw a similar curiosity in the etchings of Lenardo und Blandine by Baron Götz. Is it already available in Gotha? Gotter will find it delightfully refreshing. If only the drawings were not so untrue, occasionally eliciting more a sense of the ridiculous than addressing one’s feelings. But the overall collection is splendid and really is a singular idea.”

(J. F. von Götz, Leonardo und Blandine: ein Melodram nach Bürger in 160 Leidenschaftlichen Entwürfen [n.p. 1783].)

Frederick Duke of York

Frederick Duke of York, who may not have been as chaste during his visits to Göttingen in 1781 as Caroline assumed:

“The reason they sent him to Hannover is his love for one of the ladies of the queen, beautiful and virtuous, and whom he could even marry were the king to make her a duchess. Nevertheless they wanted to divert him from her through absence, but in vain, since up till now he has remained constant even though his seducers have set countless traps for him, they even gave him the most beautiful girls in Hannover for his service, to make the beds, etc., yet he does not even look at them…but young, without experience, open to every impression, will he always be able to resist?” “One great fault I find with him is that he has little about him of a bishop, so little in fact that it even vexes me a bit to call him such; he is neither large nor fat, and loves neither wine nor women.”

(Portrait: 1788; Royal Collection of the British Royal Family.)

Georg Ludwig Böhmer

Georg Ludwig Böhmer: Göttingen professor and Caroline’s father-in-law. On 15 June 1784, she married his son Johann Franz Wilhelm Böhmer, a man chosen for her by her family in part because of his friendship with her half-brother Fritz and in part because of his mother’s connections in Hannover and London.

(Portrait by Carl Arnold Friedrich Lafontaine; Voit Collection.)

Suitor and bride; suitor, bride, and parents.

After becoming engaged to Franz Wilhelm Böhmer in early 1784, Caroline writes disingenuously about “choices” to her friend Julie von Studnitz on 17 February 1784:

“My brother will be giving me to the man to whom he destined me from my childhood, namely, his best friend, who has loved me ever since. Through this marriage I will be fulfilling the wishes of my family, my friends, and his friends; moreover, my own heart has long been in accordance with them. Guided by all these powerful motives, I made my choice — and it was literally that same choice.”

Her brother’s wishes notwithstanding, she would, of course, first have to have the permission and blessing of her parents.

(First illustration: Göttinger Taschenkalender für das Jahr 1798, Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung; second illustration: frontispiece to Sigismund Sintenis, Mütterlicher Rath an meine Tochter, 2nd ed. [Halle 1794].)

The Engagement.

(Franz Ludwig Catel, Die Verlobung — Urania. [ca. 1776–99]; Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Graph. A1: 1394f.)

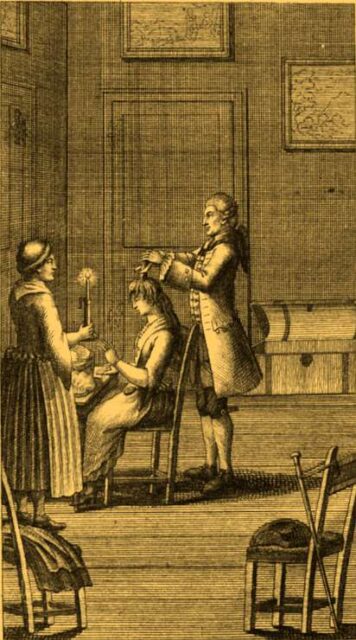

Having hair done on wedding day

Caroline recounts concerning her wedding day:

“After the midday meal I then had my hair done, while Friederike and Lotte made up the bridal wreath from natural myrtles. Then I spoke with my father and got dressed.”

(Frontispiece to anonymous, Liebesabenteuer einer alten Wiener Jungfrau. Ein Gegenstück zu den Liebesabenteuern eines alten Wiener Junggesellen [Vienna (?) 1797].)

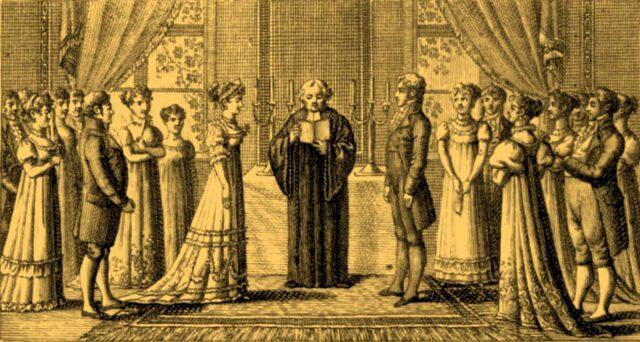

Period wedding ceremony at a private residence, as Caroline had.

Caroline writes about her wedding ceremony with Franz Wilhelm Böhmer on 15 June 1784:

“And at this moment I now saw myself next to Böhmer, for the rest of my life, and yet did not tremble! nor did I weep during the ceremony!”

(Wedding ceremony, vignette for the month of August, Taschenbuch für das Jahr 1813: Der Liebe und Freundschaft gewidmet [Frankfurt], Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung.)

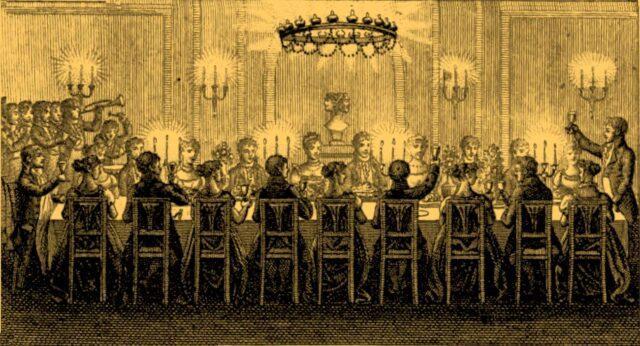

Period wedding reception dinner.

Caroline writes about her wedding reception dinner on 17 June 1784:

“We had a souper at the Böhmers. Two tables with guests. What a divine evening!”

(Wedding reception meal, vignette for the month of September, Taschenbuch für das Jahr 1813: Der Liebe und Freundschaft gewidmet [Frankfurt], Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung.)

Period illustration of the bridal night.

Caroline writes about her guests on the wedding day and the next morning:

“You can hardly imagine the friendship amid which they all celebrated our day with us. There was absolutely no thought of any silly ceremonies, not even with the garter. The next morning I was awakened by a song outside my door.”

(The bridal night, vignette for the month of October, Taschenbuch für das Jahr 1813: Der Liebe und Freundschaft gewidmet [Frankfurt]; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung.)

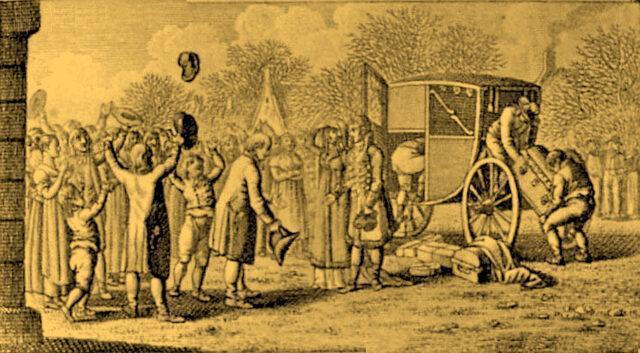

Newlywed departure ritual in a period illustration.

Caroline writes about her departure on 21 June 1784 for Clausthal after her wedding:

“Monday morning was spent taking leave from everyone . . . That afternoon we departed . . . and for the first time I genuinely felt that I was married, since now I had to follow my husband and was leaving everything behind.”

(Vignette for the month of December, Taschenbuch für das Jahr 1813: Der Liebe und Freundschaft gewidmet [Frankfurt]; Inhaltsverzeichnis deutscher Almanache, Theodor Springmann Stiftung)