“Eine Predigt über Esel” in the Berlinische Monatsschrift (1792), vol. 2, no. 6 (July 1792), 79–103.

The anonymous author presents a tongue-in-cheek assessment of the follies of the clergy and church by castigating and adducing, e.g., various artificial, self-imposed “burdens,” including, for example, that of creating a sermon “written and delivered from beginning to end without using the letter r” (81), or “when instead of using the many meaningful and instructive passages in the Bible, one diligently, as if to show off his skill, engages as the basis of what should be an edifying discourse a few expressions that are utterly meaningless out of context [as is allegedly often seen among Protestants], or, as if merely for the fun of it, expressions that today sound merely ridiculous” [as is allegedly often seen among Catholics] (84); as an example of the latter, the author adduces and extensively cites from a sermon from 1521, “How the crude person is to serve as our Lord’s ass, is to bear him and enter into Jerusalem with him etc.” The sermon unfolds from the following premise (86–87):

. . . Noah, Daniel, and Job (those are the three estates of human beings. First Noah, the prelates, who present the branches of sound doctrine and good examples to Christ. Then Daniel, the reflective ones, who walk along beside Christ submit to him the garments of virtue. And the third, Job, the real ones [the author points out: those of good works, from Germ. die Wirk-lichen], who submit to him the garments of temporal possessions through performing acts of compassion.) Thus only those, he [the preacher] says, found to be among these people will redeem their souls or be saved.

That is: whosoever would be blessed must be positioned among these three estates. And yet from within the superfluous kindheartedness of Christ (who will bless both “men and beast,” Psalm XXXVI.7), the fourth way to blessedness is prefigured by the ass of our Lord, which represents the penitent ones who bear Christ personally. For though they have no virtue, and sing quite ill, with the voices of asses, and possess nothing etc. — nonetheless they can serve Christ in the place of the ass, bearing him in both body and soul, thereby entering into glory with him. — Hence though you yourself rule no one, advise no one, help no one, possess nothing etc. — you are nonetheless our Lord’s ass.

Thou shalt be our Lord’s ass for the following four reasons etc.”

These “reasons” include reference to the ass serving with its body, which constitutes a “more meritorious service” than serving merely with one’s “mouth, heart, or works”; to the ass’s more surefooted gait, without error insofar as Christ guides it with reins; to the ass’s closer proximity to Christ, the Lord being “closer to those of downtrodden heart, who feel Christ even though they may not see him”; and finally to the fact that the ass serves Christ more honorably by serving solely Christ rather than, e.g., being a “servant of other servants” as are prelates (87–89).

The author next remarks that “this notion naturally brings to mind Laurence Sterne’s (or Parson Yorick’s) [in Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, 6 vols. (London 1759–67)] ‘Sermons on Asses,'” which, as the author says, “seems to me to be more familiar to us [the Germans] because of its unusual title than because of the many splendid things those sermons contains” (90). Here two period illustrations from the German translation (Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, Illustration zu Tristram Shandy [1776]; Herzog August Bibliothek; Museums./Signatur Chodowiecki Sammlung [7-540] and [7-542]):

Laurence Sterne published his own sermons as The Sermons of Mr. Yorick, 7 vols. (1760–69) in connection with his novel Tristram Shandy, and the anonymous author now cites extensively from four sermons involving “asses” from the German translation Predigten von Laurenz Sterne (oder Yorik) aus dem englischen übersetzt (Zürich 1766; 2nd ed. 1769) after discussing the differences between the “tone” used in English and German pulpits.

(1) “According to the English translation of the Bible, there are two burdens between which the strong donkey Issachar has “bowed his shoulder ” (Gen. 49:14–15), burdens here interpreted as civil and religious servitude” (91). Here the preacher speaks against those who would keep people in the dark, delivering them over, “as soon as they come from the hands of the midwife,” into the hands of priests, “whose primary principle of education is that ignorance is the mother of all devotion” (91–92).

(2) The second sermon begins by wishing that the children of Issachar had all died out in the first generation; instead, one now finds its descendants in the church and in the state, from the favorites of prime ministers on down to the lowliest serf of the bishop (92). The preacher goes on to question the necessity and even legitimacy of dogma, conciliar decrees, ecclesiastical commands, and the like as impositions on the conscience of Christians — who are to have but one Lord — such impositions serving only to turn freeborn Christians into “Issachars” (94). Indeed, telling people that the Holy Scriptures suffice for all things in religion and yet insisting that people accept human dogmas — does that not amount to treating people like asses (95)?

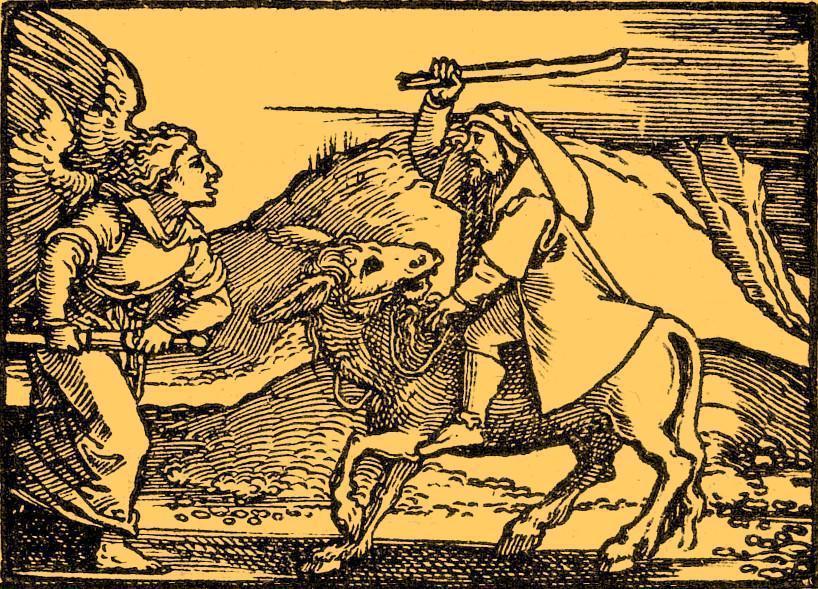

(3) “The first two sermons take the strong ass Issachar as their text; the last two take the donkey of the prophet Balaam, who said to the latter, “Am I not your ass, which you have ridden all your life to this day? (Numbers 22:30)” (96) (Sebald Beham, Bileam und die Eselin [1533]; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum; Museums./Signatur HSBeham AB 3.20rH):

The sermon goes on to explicate the assertion that those who understand the New Testament will reject any dominion over their conscience save that of Jesus Christ (97), also rejecting any mixing of the offices of state and church, the key to Christian freedom being the freedom of conscience (98).

(4) The fourth sermon begins by noting how, as a matter of fact, one does not expect an ass to speak as this one does to Balaam (“Am I not your donkey etc.”), and notes how lamentable it is that reasonable beings imitate such a lowly, servile creature, slavishly serving despots and asking the same question, “are we not your asses?” (98). The sermon compares with “reins” the confessions of faith for which distinguished English bishops, in their hearts, care nothing and yet with which they oppress others (98). The concomitant observation is that religious ignorance flourishes best where human ordinances are most followed most zealously — even though our Lord himself stood before Pilate and declared that his kingdom was not of this world.

Hence though the emperor may well have the right to intervene in kingdoms of this world, he does not have the right to intervene in those not of this world (100). Unfortunately, so the conclusion of this sermon, there is no shortage of asses among the people to serve the ends of those who presume themselves to be prophets. That is, “although Balaam and his ass have already been dead for many centuries, their descendants are yet quite numerous” (103).

Translation © 2011 Doug Stott